Could We Build an American Orania?

Orania: Building a Nation by Jonas Nilsson

Welcome back, and thanks for reading. I have discussed Orania, the Afrikaner-only town in South Africa, before, namely in an article on it and South Africanization, and a podcast interview with Joost Strydom, the CEO of the Orania Movement, which acts as the media side of Orania. However, as it has been a while and recent podcast guest Jonas Nilsson sent me a copy of his Orania: Building a Nation, a short book with numerous important lessons, I thought the matter would be worth reviewing again, with a focus on its relevance to Americans. All those who are not yet paid subscribers: while some of this article is free, please subscribe for just a few dollars a month to support this project, get access to audio episodes, and read this article in full. Finally, please tap the heart to “like” this article so Substack knows to promote it. Listen to the audio version here:

2 to 3 violent incidents of civil unrest daily. 80 murders daily. 80 hijackings daily. One woman raped every 4 minutes. 3 to 4 kids murdered daily. Such are the grinding crime statistics of South Africa,1 the land known for its stomach-churning farm murders and a major political party that holds rallies in which it chants about butchering the state’s white residents. To live there as a white is to live as a second-class citizen, and to live with the Sword of Diversity hanging over one’s head at every moment.

What can one do when faced with such a situation, particularly when outnumbered to such an immense degree as the Afrikaners are? Fleeing is one option, but it will mean the extinction of your culture forever. You can try to make deals with those who hate you, but bartering with those who’d love nothing more than to chop off your head is rarely a winning strategy. Living behind the gates in a secure private compound is always an option…until the hordes come for that too and ravage it like locusts.

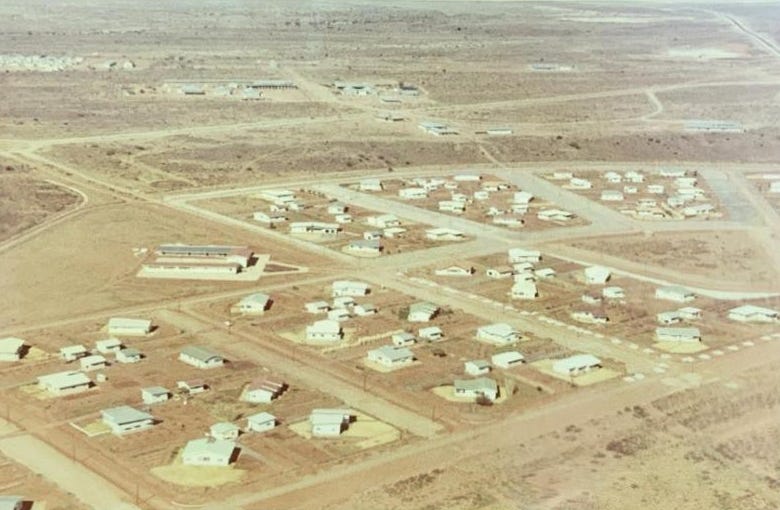

The final option is to separate while keeping your identity intact. To march into the desert and build something new in a spot where the ravages of diversity don’t exist and won’t come, where the lack of natural resources means the incompetent government will be generally ambivalent about what you’re up to, and where you have the opportunity to live as your ancestors would have.

That is the Orania option. As the rest of South Africa inexorably slides into utter anarchy and dysfunction, the town of Orania has remained the only exit option that doesn’t mean the cultural disintegration of the Afrikaner people. It is a place where they can live, work, and build without living under the oppressive thumb of the race communist regime. It’s also, after all, the one town in South Africa to have escaped much of the South Africanization process.

For those Afrikaners who wish to live a Christian life in which one can build something anew that has a chance of lasting even while much is crumbling, it is the one real option…and is growing at a breakneck pace as a result. This makes it interesting, and also a story full of gleanable lessons for those Americans who are desirous of getting away from our South Africanizing world.

However, its situation and the situations of those living in it are also very different from what Americans interested in recreating such a project here might face. That is often forgotten by those who are interested in it, or lost in the race of trying to make it seem relevant and fit America’s circumstances, making many of the details about what it really is and the analysis surrounding it quite muddled.

So, in this article, I’ll attempt to correct that by using Nilsson’s book as a basis for sharing what Orania is trying to accomplish, in what ways it is and isn’t relevant for Americans, and then give a brief review of the book. I would recommend checking out the footnotes, as they have some interesting passages from the book I thought would break up the narrative of the article too much, but are worth reading.

What Is Orania?

When the apartheid government gave up the reins of power in 1994, handing things off to the former communist terrorist Nelson Mandela and his ANC gang of kleptocratic thugs, it did so from a not entirely weak position. Sanctions had bitten, causing inflation and straitened economic circumstances, but the Afrikaners of the country were still largely organized and mobilized, giving their politicians a good bit of heft in making demands of the other parties with whom they were negotiating. Additionally, the Afrikaner military and intelligence establishment was top-notch, and defended borders meant the white population of the country was not yet as woefully outnumbered as it is today. So the ANC knew that failure to satisfactorily compromise would mean the Afrikaners walking away, and potentially harsh military reprisals.

Naturally, the honorless cretins in charge of that communist terrorist-composed political party figured they could just agree then and renege later, and so went along with the charade of negotiations. That repudiation of past pledges of fair dealing has largely happened, such as with the land expropriation law, but the Afrikaners did get a few important concessions out of them. The most important of those, in Orania’s case, is Section 235 of the Constitution, which explicitly allows the existence of communities with a shared culture and language to govern themselves, and to exclude those who don’t fit their strict criteria.

That provision came about because some Afrikaners were planning ahead, and understood that to trust the ANC to deal fairly with whites—particularly the generally more right-wing Afrikaners they so despised—was to be a fool. Relatedly, they saw that the best way of going about surviving the “Rainbow Nation” was to decamp from it to the largest degree possible, and to get what written guarantees for such soft secession they could, so the “international community”-reliant ANC would be forced to mostly go along with it for so long as such things mattered.

Further, they knew that anywhere obviously rich and pleasant would just get taken over by the locust-like hordes of squatters and kleptocrats, so they chose not the thriving and fertile Western Cape but the Karoo desert as the center of their ambitions. None of those who would steal from them want to live there, and it’s an open question of whether the utterly incompetent ANC government could even get forces there to crush them, at this point.

Out of such foresight and concern, Orania was born. It was meant to be an Afrikaner-only community from the start, and one ruled by a private stock company to ensure the town’s future is kept in the hands of those with the vision to the highest degree possible, minimizing the chances of government interference or liberalizing changes that would destroy the project.

To a large degree, the town has succeeded in creating the reality its founders wanted. It has its own electric grid, a town bank that provides a “coupon” that essentially serves as a town-only currency, its own social services, and it governs itself rather than being governed by the closest municipal government.2 While still beholden to the national government, it has carved out a niche of special sovereignty status for itself that generally allows it to decide the exception in a more real and frequent way than, say, a typical town or city does.3

Importantly, this independence is not just a bit of ink on paper—as most constitutional guarantees are—nor is it something in which a collection of old fogeys on the town council believe but the youth can’t wait to escape from. It is, rather, a way of life for the town’s residents. As Nilsson puts it, Orania as a community is set apart by the fact that “the desire for independence and self-determination isn’t a divisive issue but a shared goal. The inhabitants of Orania are united in their pursuit of these objectives, making their collective will clear and undisputed.” That unique state of things exists because the community recognizes that self-governance by its very nature requires discrimination and exclusion,4 and so all who aren’t willing to be fully part of that which Orania represents are excluded.

That lack of diversity has not made the town weaker, as the “diversity is our strength” chanters would have one believe. Instead, it has been the foundation of the town’s success. Unlike pretty much everywhere else in South Africa, it is growing, and growing at a breakneck (>10%) clip. Housing prices are rising as Afrikaners flee the disaster that is South Africa and pour into it. Crime is a nearly non-existent problem, rather than a fact of everyday life as it is everywhere else in the country. All this and more, from the safety advantages to the functioning municipal services, mean those Afrikaners who fit the bill are flocking away from general South African society and to Orania.5

It also means the Oranians can do the sort of pro-social things we who are forced to tolerate diversity cannot. For example, while in America and non-Orania South Africa, the price of homes is really the only factor by which one can discriminate, meaning those who wish to avoid diversity and its evils must shell out immense sums to avoid “young scholars” firing handguns over scuffed sneakers, Orania can and does simply keep such scholars away. As a result, the town can engage in philanthropy and banking practices that help less well-off but committed and hardworking residents afford homes,6 something that would essentially just mean letting the enemy in the (expensive) gates anywhere else.

That it can do such things, and is filled with a citizenry who are honest about why they don’t want to live around other people groups and are willing to do what it takes to keep those unwelcome “newcomers” away,7 makes Orania a much stronger and more vibrant place. All the residents are not of the same narrow wealth and income band, there is less socio-economic hostility or instability, those who do less remunerative jobs don’t have to fear living around feral savages, and so on.

Because the town is united behind a shared purpose and screens out the bad elements, the economy can serve the people rather than the other way around. This is critically important, as having the Afrikaner residents do all the work—rather than relying on low-wage blacks or immigrants—is an integral part of Orania’s plan and identity, making affordable housing for those who do such work necessary in keeping Orania functional.

Such a state of things is utterly impossible when it is illegal to recognize that equality is a false god, but quite effective at building cohesion when the exclusion and discrimination necessary for self-governance are prioritized.

All in all, Orania has a functional social contract, whereas South Africa—and most of the rest of the West—does not. In non-Orania areas, taxpayers are endlessly sheared and sometimes flayed so as to fund the lifestyles of their inferiors; South Africa has a 4:1 welfare recipient to taxpayer ratio, and nearly all of the net taxpayers are white. In exchange for paying for everything, they get murdered in their homes by criminals with whom the regime sides, while that regime fails to even provide basic services like reliable electricity or clean water. Life in New York or Memphis is little different. Naturally, those who can want to move somewhere where they at least get something for their taxes, as Nilsson notes:

As Orania develops its political and economic autonomy, an exponential curve of “push” and “pull” factors will become increasingly apparent. This dynamic becomes particularly clear when comparing Orania’s free-market-oriented economic model with South Africa’s increasingly socialist orientation. While South Africa grapples with a failed infrastructure, increased insecurity, and spiraling tax burdens, Orania emerges as an enclave of stability and efficiency.

For the white citizens of South Africa, the question of “what am I getting for my money?” is becoming increasingly acute. They see a state that not only fails to provide basic services but also taxes them heavily for the privilege of living in a dysfunctional nation. In this context, Orania is likely to emerge as a future tax haven, a place where taxes actually go towards building and maintaining a functioning infrastructure and society.

And while Orania is currently a relatively small town of a few thousand, the essentially uninhabited desert around it means it has the room to grow. Further, its sane and pro-social efforts at encouraging home ownership, having valued residents do all of the work, building a durable and sustainable economy from the ground up, and only letting in such residents as fully adhere to its vision of the good, mean, when paired with its answering the social contract question and being a breath of fresh air from the decay and dysfunction of everywhere else,8 that Orania’s future is quite bright and larger than many imagine. As Nilsson notes:

Orania compares itself to other prominent examples of small but economically robust nations and cities. These include examples like Singapore and Hong Kong, which despite their limited geographical area have managed to develop successful and diversified economies without relying on a dominant primary industry.

Interestingly, Orania’s potential organic growth area could be compared to Rhode Island, the smallest state in the USA, both in terms of geographical area and population. This provides an indication of the scale of autonomy and self-governance that Orania aspires to achieve. Other small countries like Malta and San Marino also serve as inspiring examples of how a small area doesn’t necessarily have to be a limitation for economic and social development.

Of course, Singapore, Malta, and Hong Kong are immensely valuable deepwater ports in strategically important regions, which makes the comparison somewhat inexact. But Orania isn’t plagued by “diversity” or the mind virus that leads to it, which is a huge advantage. Would one rather invest and live in a port likely to be full of the various problem children of the world, or a town without such advantages but also with strong Christian values and no “young scholars” or leftists? At the very least, it’s a toss-up, and will lean more toward Orania as the costs of diversity continue accruing on the liability side of the life ledger.

And that is what Orania is. It is an Exit option for those who have the courage to understand that, as Nilsson puts it, “the path to freedom is not through reform or negotiation, but through bold determination and innovation” and that they’d be better off bearing the costs and inconveniences of building civilization anew in the desert than in trying to continue existing in a land ruled by those who want to kill them.

That is what makes it beautiful and successful, and the sense of purpose inherent in the project and those willing to embark upon building civilization anew—the physical act of building an independent nation—creates a continuing sense of purpose that drives its residents to do and be their best. Nilsson tells a wonderful story in this regard:

This sense of independence and determination is not just confined to the legal and political realms. It also resonates deeply in the day-to-day lives of Orania’s inhabitants. Take, for instance, a team of carpenters I met there. I have encountered many carpenters who take immense pride in what they have built, being able to point to a house and say they’ve actualized it. However, I have never seen such pride as I did in a carpenter I met in Orania. In his workplace, alongside his team, they were building a terraced house. But in his eyes, he wasn’t just building a house for someone to live in - he was building a nation. The joy, enthusiasm, and pride he expressed were unparalleled; each brick laid was a step towards realizing the dream of an independent homeland. This deep-rooted connection between their labor and the progress of their community is yet another feature that makes Orania truly unique.

How Relevant Is Orania for Americans?

So, is Orania relevant for those of us who live in America? Somewhat. There are reasons it is relevant, and many ways it isn’t. As the latter determines the former, I’ll cover them first.

![[Audio] Could We Build an American Orania](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!70Bh!,w_140,h_140,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-video.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fvideo_upload%2Fpost%2F187524300%2Fda686773-44ad-415c-9b97-2f8fc34f4a32%2Ftranscoded-1770738038.png)