What McKinley Understood that the Consultant Class Doesn't

Rebuilding the Industrial Economy

Welcome back, and thanks for reading! I have heard that many subscribers prefer the free articles to be generally shorter. So I have attempted ot keep this one short and to the point. It was a point that came up as I prepared for an upcoming podcast of the McKinley Administration, and one I thought would be well worth discussing in the context of the Trump tariffs. as always, please tap the heart to “like” this article if you get something out of it, as that is how Substack knows to promote it!

Much has been made of the Trump Tariffs as of late. Between the fight over rare earth minerals, the continuing feud with China, and the record-breaking revenues being brought in by the new tariff regime, the minor details of varying tariff rate schedules and in what ways they might ultimately be implemented have risen to the fore. In the process, that has obscured the most important detail in all of this: what the point of the tariffs, and indeed having an industrial economy we prioritize, ought to be.

This can be seen in the criticisms from the consultant class types, who have whined endlessly about the short-term results of the tariffs. They’ve pointed to minor increases in input goods costs,1 whined about the costs of importing cheap consumer slop from China,2 and insisted that there should be no impediments to buying critical goods like computers from enemy nations, namely Red China.3

Of course, such buffoonishness is to be expected from the sorts of people behind the corporate raid insanity of the 1980s,4 and the continuing consequences of the globalization push that soon followed. “Efficiency brain,” the belief that economic outcomes can and should be closely modeled and whatever the model shows leads to the most “efficient,” generally meaning lowest current cost, outcome to be should be done, has wreaked havoc in the American industrial sector for years.

They’re how we became dependent on China for rare earth minerals, Taiwan for semi-conductors, and ran out of input goods during Covid because of the extremely fragile, globe-spanning just-in-time supply lines used by most modern manufacturing companies. In the short term, they were right: those moves did lower costs. In the long term, the view they forgot to consider, our national security and the virtuous cycle of industrial development that made us the world’s foremost industrial power, has been broken thanks to the very decisions they recommended.

Fixing that catastrophe—onshoring industry, giving it the chance to be profitable, and maintaining the virtuous cycle of the old American System—is what the tariffs are supposed to accomplish. Such is what the approach to tariffs that William McKinley took as a congressman and president shows, and what the efficiency-brained bean counters have missed.

Listen to the audio version of this article here:

The McKinley Approach to Tariffs

The American System

To frame tariffs and their outgrowths as purely a matter of cost, as the free trade contingent always has, misses the point. While costs do matter, all else being equal, it is rather the functioning of the political economy—the combined political and economic system—that leads to those prices that is paramount.

The question is whether prices are low because the American people are being flooded with foreign imports that cause immense havoc and depression in our domestic manufacturing sector, or if that domestic sector’s continued success—paired with a strong and stable currency—means natural deflation sets in as productivity enhancements, innovation, and long-term success drive them down.

Such was long the understanding of the dominant faction in American politics, as shown by the American System that helped push America into an early period of prosperity.5 The system they created, the American school of political economy, focused on achieving economic prosperity and independence by enacting a relatively high tariff, stimulating domestic industry that then had an opportunity to succeed because of the tariff, funding internal improvements that connected the national economy so as to make those industries larger and more profitable, and remaining politically stable by remaining economically prosperous.

The key to this system was the tariff. Though the revenues garnered by it were important, they were not its main purpose. Rather, as understood by the American System school of thought, the goal was to stimulate investment in both the American industrial sector and, even more importantly, the workers who could perform ever more highly skilled tasks in that sector.

McKinley and the Tariff

Such is where McKinley comes into the story. Over the course of the first two-thirds of 19th Century, the American System had remained largely intact, other than Jackson’s destruction of the national bank. Over that period, America went from being largely reliant on British industry to being able to produce most of its own goods. Shielded from a destructive flood of British imports by the tariff, our textile industry clothed the nation, our iron industry became competitive and increasingly provided the rails necessary for the early railroads along with the ingots necessary for early industry, and more and more day-to-day goods became produced at competitive prices by growing and profitable American companies.

But then the American System started breaking down as a resurgent Democratic Party adopted a befuddling mix of pro-inflation monetary thought from the silver crowd and free trade ideology from the Manchester School of economics.6 If implemented in full, such a system would mean inflation at home as industry was left unprotected from ferocious and predatory foreign competition, a disaster for the business community and those reliant on it for employment and prosperity.

Such is how Republican politician William McKinley became relevant, as it was out of such a stew that he rose, and against the free trade stance that he fought hardest, recognizing that a debate purely about matters of price was unhelpful, as it missed the larger point of the tariff.

This is something that Professor H. Wayne Morgan makes clear in his masterful William McKinley and His America (though I normally recomment Leech’s In the Days of McKinley, as it is a more fun read, Professor Morgan’s book is an excellent and much more scholarly work on the subject): McKinley remained unconvinced by the arguments of the free traders and the efficiency-brained policy quacks because he thought not in days and months but rather over the long term.

Take the price of steel, perhaps the most important input good of the Gilded Age, given the prodigious quantities in which it was needed for the railroads, engines, steamships, and skyscrapers of the period.

Was it cheap steel that mattered most for the continued success of the American economy? If so, then Britain’s long-established steel industry could produce it much cheaper than the fledgling American steel industry of the 1870s and 80s: why not just import it from them at the lowest price possible?

The classic answer of the American System’s supporters is that of economic independence and national prosperity.

For one, doing so would blot out the fledgling American steel industry, and leave us prey to a semi-hostile foreign power, reliant upon it for the key input good of the civilian economy and the all-important navy. Without a reliable source of steel, we could produce neither railroads nor battleships, neither towering buildings nor heavy guns. And, after making us reliant on their product and devoid of the highly expensive foundries in which it could be produced, the British could just raise their prices, and we’d lose the cost advantage that led to the disastrous decision in the first place. We would be reliant on appeasing them for our continued national prosperity, and no longer independent.

Further, in crushing industry that was yet unable to compete with established European competition, removing the tariff would strike an indelible blow to the American worker. Instead of working in a country and sector where his wages could rise as the company grew prosperous and he would learn more and more skills while rising in the ranks of an ascendant and stable industrial concern, he would be thrown out on the street in the name of temporarily cheaper prices for a good the country would be unable to produce, for it had lost his skills and the opportunity to train him yet more. As Morgan notes:

[McKinley’s] whole tariff theory rested on two assumptions: that the tariff produced high wages at home, and that the American system of his day was not ready to face foreign competition. The home market must be guarded to sustain both American labor and industry. His constituents included workers, and he watched their interests zealously. “Reduce the tariff and labor is the first to suffer,” he said in his first major address on the subject. “He who would break down the manufactures of this country strikes a fatal blow at labor. It is labor I would protect,” he reiterated in 1883. He scorned those who felt that wages should seek their own level. “We do not want fifty-cent labor,” he retorted on being told that it would be available were it not for protection. The security that protection afforded to labor buttressed his American ideal. “Here the mechanic of today is the manufacturer of a few years hence.”

But that was not all. The American steel industry did eventually become hugely successful—in large part thanks to the protection and breathing room afforded by the tariff, as is recorded well in Andrew Carnegie by David Nasaw—and prices for the critical good fell to the point where they were competitive with British steel. Should the tariff then be removed, so British steel could flood the market and drive down prices?

In McKinley’s view, certainly not. All else being equal, of course, lower prices are better than higher ones. But all else is never equal. Ever-lower prices, if that trend were driven by foreign dumping of goods rather than the naturally deflationary tendency of the American market, would not just mean low costs for the singular good at issue.

They would instead mean economic depression. The steel barons could no longer afford to invest in innovations and productivity advancements in their titanic, highly advanced facilities. Workers would either lose their jobs or see their wages cut. The steel companies could and would buy less coke and ore, driving mines out of business and miners out of work. Thus, the railroads would have less to transport, and would fire workers as they defaulted on bonds, causing an economic panic.

In short, such a situation would mean hard times brought about in the name of efficiency. Because of how the industrial cycle of investment and production worked, prices driven below the point of profitability by foreign competitors dumping their goods here would not mean cheaper production costs but would rather mean hard times, layoffs, and depressions. As Professor Morgan notes:

[McKinley] was deaf to the old cry that the tariff raised prices, for to him higher wages more than offset any such rise. He rested his whole theory on the assumption that cheap goods meant hard times. “When prices were the lowest did you not have the least money to buy with?”

As McKinley understood, the tariff served a valuable purpose: it turned the United States into something of a walled garden where manufacturers could focus on competing with each other to build valuable, profitable, and innovative businesses without worrying overly much about the vagaries of Britain’s industrial economy.

Such a situation had secondary and tertiary benefits.

For example, it meant mines would be built in America, and innovation would pour into them—as happened with the Mesabi ore range,7 and the massive buildout of rail and ship infrastructure to support them.

Further, it meant innovators would pour capital into even more innovative and ambitious undertakings, such as Edison’s attempt at a magnetite mine to produce iron ore. While a failure as a mine,8 it was still a massive spur to innovation, and the advancements spawned by it turned into the wildly profitable Edison Portland Cement Company.9 Without the tariff protecting and stimulating the steel industry, that innovation, investment, and development wouldn’t have happened.

Importantly, such a system was still internally competitive—so long as industrial cartels were prevented—and so prices naturally fell as the best companies in America rose and outcompeted their domestic rivals, something best achieved by Carnegie: in the end, the cost benefit came, but on the back of prosperous and advancing industry rather than investment-destroying imports.

Meanwhile, the tariff also meant that workers were looked after, as the companies that employed them were succeeding and paid better wages for better-trained men. Though the impression of the Gilded Age is one of workers being squeezed ever more harshly, that is largely untrue: the cost-of-living-adjusted wages of an average worker rose by a massive 40% from 1860 to 1890, and amongst industrial workers grew by 59% from 1880 to 1890 alone.10 A free trade system would have seen them dispossessed by a flood of cheap goods with which their employers couldn’t compete, as later happened in Britain. The tariff meant their lives generally improved.

In the face of such titanic strides forward—key industries improving by leaps and bounds alongside the buildout of vital infrastructure, workers growing better off, and innovations happening at a breakneck rate—what was the upside to worrying about trade deals that would fail to let us enter new markets while thrashing the domestic market? There was none, and McKinley realized it:

Foreign trade did not lure him. “The ‘markets of the world’ in our present condition are a snare and a delusion. We will reach them whenever we can undersell competing nations, and no sooner. Our tariffs do not keep us out, and free trade will not make it easier to enter them.” Protecting the diverse home market from unfair foreign competition allowed free trade within the United States, and competition among manutacturers insured fair prices and good wages.

What McKinley wanted—the attitude that defined his time as a congressman (which all the above passages reference), led to the famous McKinley tariff, and guided his time as the president—was the encouragement and development of a virtuous industrial cycle.

As he and others in the American System school of thought conceived of it, such a system was one in which capital is poured into productive industrial or infrastructure concerns that are then forced to compete with each other while being kept safe from predatory trade tactics engaged in by established foreign competitors. The resultant stimulation and competition lead to that capital being poured back into new investment, innovations, and enhancements in worker productivity. As a result, such a system would mean new and better factories, a more highly skilled workforce, better goods, and—eventually—naturally lower prices.

This was a virtuous cycle in which investment in one area generally meant cascading improvements in the others, and the vector of the American industrial economy was quite good. Describing such a system, Professor Morgan notes:

All men have dreams. McKinley’s came to be that of an all-inclusive nationalism that might not blot out party divisions on the great national issue of the day, but would at least rise above them. To him the basis of that nationalism was the protective system that worked for all sections of the country. His great personal desire for order became in his public life a demand for national unity and cohesion. He frequently referred to the Founding Fathers. He admired the nationalism of Henry Clay and the old Whig party. His efforts to make that nationalism the basis of the Republican program stamped him as a leading nationalist in American politics at the end of the nineteenth century. He worked for a new American system. He wisely decided at the beginning of his career to identify himself with a national issue. It was his good fortune to believe in that issue and what it represented.

Fortunately for America, he mostly succeeded in creating such a system.11 America became the world’s foremost industrial power, a titan first amongst other titans and then—after World War II—with nearly no “free world” competitors. Our corporations were tremendously successful, largely innovative, and worker pay was quite good, largely keeping up with inflation and productivity gains.

Rejecting the Virtuous Cycle

That then changed in the 1970s. Rejecting nearly a century of success that had been premised largely on a McKinley-style modern interpretation of Henry Clay’s American System, a collection of domestic interests chose to favor finance and globalization over a domestic virtuous cycle of industrial development.12 While they had reasons for doing so, namely the insanity and anti-productivity attitude of Rust Belt unions in the period,13 the resultant globalization has been a catastrophe of the very sort McKinley would have predicted.

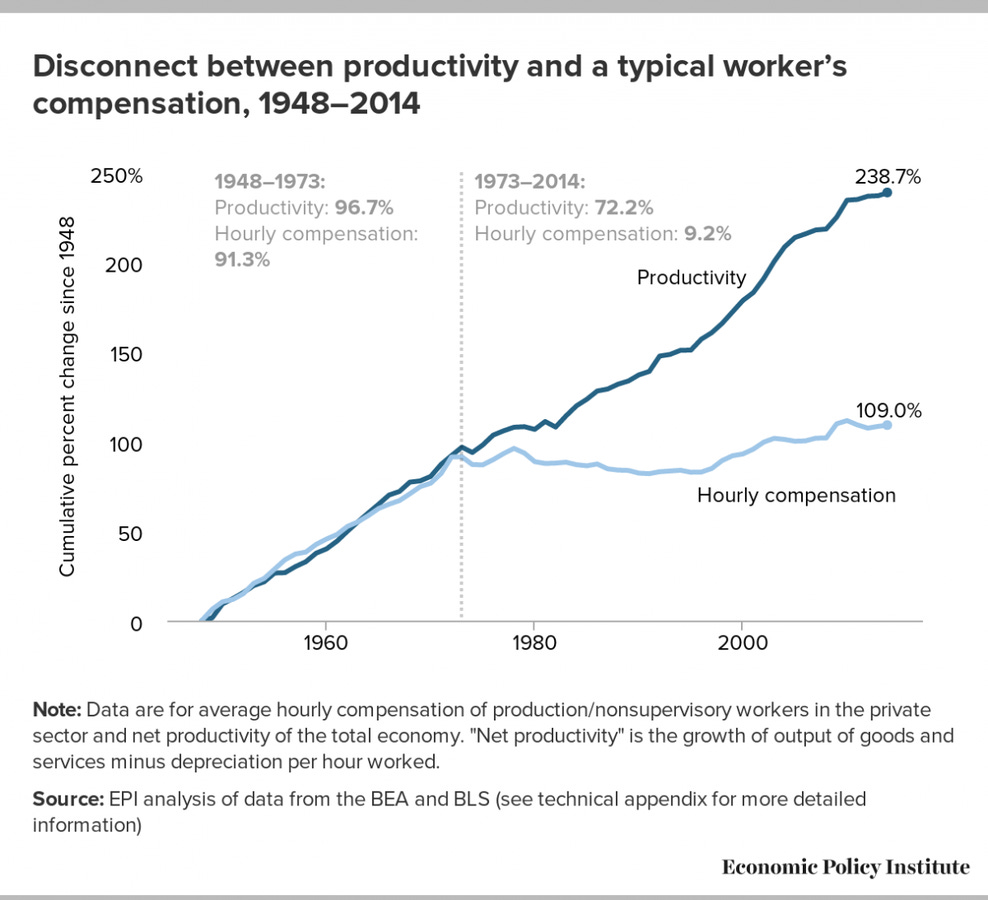

For one, worker pay has stagnated in the face of massive foreign competition, even as productivity advances keep happening. The sort of “50-cent labor” McKinley rejected is here, and the result is that wages have not kept pace with critical, real-world assets like housing. Though worker productivity continues to increase, wages are no longer keeping pace with it, as those in charge have the whole world’s labor supply with which they can push wages lower.

That means we no longer have the continually improving workforce necessary to keep the virtuous cycle of the American System working. As my friend Rust Belt Kid noted on our recent podcast, decades of depressed wages mean the sort of highly-skilled Americans who can do the industrial jobs and teach the next generation how to do them are missing. The people who would be helping us reindustrialize and build an ever more productive industrial sector were offshored, laid off, or quit in disgust, and now simply don’t exist.

Paired with that has been the drift toward financialism over industrialism. Such is the path Britain followed in the early 20th century, when it chose the financial instruments of the City of London over reinvigorating its industrial base. As Charles Emmerson notes in his 1913:

But the growing importance of the City to Britain’s economic arrangements was not uniformly welcomed. Was the country not simply living off its wealth, the product of its former labour? Did the City strengthen both nation and empire by placing itself at the crossroads of global finance, lowering the cost of money in London into the bargain? Or was the City, so important and yet so vulnerable to a changing international scene, a source of potential weakness? By creating opportunities for British investors to send their money abroad, was not the City denying investment to industry at home?

By the end of 1945, Britain’s foreign investments had been liquidated in the name of funding wartime expenditure—with the state selling what factories and capital its subjects owned abroad to pay with gold for war goods it could now no longer produce—and it concluded its last great struggle thoroughly exhausted and unable to rebuild.14 Financialism had cost it everything.

America chose a similar path, with results that are increasingly looking similarly dire.

For example, we invented the semiconductor, much as the British invented the steam engine or Bessemer steel, and should be able to produce them here. While we do still produce some, our domestic semiconductor industry is declining, and we rely on massive exports of the critical goods from Southeast Asia, particularly Taiwan, which took advantage of our lax policies to become a critical semiconductor hub.15 As our most likely potential war of note concerns China—or its semi-allies like Venezuela and Iran—letting the Taiwanese do so seems like an increasingly bad choice.

The same is true of other critical inputs, as steel once was (and still somewhat is). The refining process for rare earth minerals is nearly entirely controlled by China.16 Our car parts are produced in Mexico.17 Our fiberglass market—critical to aerospace and defense—was crushed by flooding from the Chinese market, then the remnants were bought up by foreigners.18

That fiberglass problem gets to the larger issue: Owens-Corning and its fiberglass business are sometimes given as the key example of American innovation and resilience in the face of predatory foreign competition. While that might have been true some years ago, the business was destroyed by Chinese dumping tactics during the Biden Administration and was just sold off to the Indians.19

McKinley-style tariffs would have prevented that from happening, and the virtuous cycle would remain intact, with Americans being employed by Americans and backed by American capital as they built a key business and learned the ever more complex skills associated with it. Such has happened in the tactical firearm market, for example, which is shielded from foreign competition and is now immensely profitable and innovative.

That is the key point, the matter the efficiency-brained consultant types that are currently howling about the marginal cost increases seen with tariffs20 don’t seem to understand: it is not the price of a given good a week or month from now that matters, but whether the cycle that creates that good is inherently deflationary and iterative, or one that puts us at risk of foreign predation.

Allowing enemies to put domestic manufacturing concerns out of business is very much the latter. Worse, as has now happened for decades, it destroys the formerly virtuous cycle. In putting the next generation of manufacturing employees and businessmen out of work, displaced in favor of some sweatshop in Bangladesh, it means we no longer have the generations of interested, capable industrial workers we once did. Men who would work somewhere, learn the ins and outs of the business, and then use what they had learned to innovate and build a new process, a new industrial concern, or perhaps even a new industry.

Thus, right now, the human capital and technical know-how simply isn’t there as we attempt to reindustrialize.

What the tariffs must do, then, is give what industry survives in America the chance to recuperate and focus on restarting that cycle by training the next generations of industrial workers, leaders, and industrialists. We need more bright and adventurous engineers like Herbert Hoover, not to mention petroleum and mining-related engineers of the sort that we are in very short supply of. We need more guys who can do the industrial work, and companies willing to pay the wages that encourage them to do so. We need to reward and encourage innovation, rather than drowning it in union obstinance and red tape. We need to encourage natural resource development and exploitation rather than burying it under environmentalist red tape. We need to reprioritize the real world over the financialist Fugazi.

That will mean higher prices, at least in the short term. But, if done correctly, it will also mean higher wages and jobs with dignity instead of service industry serfdom. It will mean successful, real-world companies building again. It will mean reinvestment in old infrastructure and building out the infrastructure of the future—particularly high-speed rail, space access, and nuclear energy.

Things won’t be fixed tomorrow. That’s not how it has ever worked. But there are causes for optimism. We could rebuild our electrical infrastructure supply chain,21 make huge strides forward in the related nuclear industry,22 and otherwise build out the industries of the future. We could encourage the domestic production of high-quality, wholesome foodstuffs—regenerative beef comes to mind—and improve the health and employment prospects of the average American. We can build the factories of the future,23 and upskill the workforce so that those factories provide good jobs for high-quality workers again.

All of that is possible, and all of it would prove hugely salutary for America, but doing so will take time and a great deal of effort. Most of all, it will mean a reinvigoration of the old American System that did so much to build our great land and the people within it. Such is what McKinley accomplished all those years ago, and it’s what we need to accomplish again.

If you found value in this article, please consider liking it using the button below, and upgrading to become a paid subscriber. That subscriber revenue supports the project and aids my attempts to share these important stories, such as the recent one on Civil War, and what they mean for you.

This story is told well and entertainingly, with just the right amount of technical detail, in Thomas Edison by Edmund Morris

According to the US Census, wages over this period rose from $380 in 1880 to $584 in 1890. It helped that there was no depression in this period.

As gold was worth ~$20 an ounce over this period, that meant they went from earning, in today’s terms (assuming a $4000 price of gold per ounce now) $76,000 to $116,800

Amongst other books, this is covered well (though broadly) in The Tycoons: How Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller, Jay Gould, and J. P. Morgan Invented the American Supereconomy. For many decades, America succeeded in iterating on each improvement and investing tremendous sums in their use, leading to an immensely powerful industrial economy

My favorite article on this is called Operation Glassheart. It provides, in part:

One path forward, favored by industrialists, military hardliners, Texas conservatives, Howard Buffet, John Birchers, and America First Buchananites, favored tolerating a painful but honest restructuring: devaluation of the dollar, higher interest rates, keeping US supply chains at home, and re-affirming a national commitment to energy, labor, and food sovereignty. Under this model, gold convertibility could have been preserved—at a higher price—and the dollar would have continued to function as a smaller and devalued global currency backed by the tangible output of American labor, land, and industry. These thinkers however never really had institutional dominance, but relied on powerful voices across the military and representatives of America’s core middle class. Oilmen, miners, farmers, and manufacturers.

The other path, which ultimately prevailed, was driven by a coalition of financial elites and geopolitical strategists who were already well-entrenched within elite American institutions. The Council on Foreign Relations (CFR), The Brookings Institution, economists at Harvard and MIT, the Trilateral Commission, and the IMF/World Bank Atlanticists were already coordinating to push for a world where national sovereignty would be subordinated to multilateral governance networks ruled by Wall Street and the State Department. They argued for building a new system: one based on the dollar’s role as the global reserve currency, backed not by America’s raw manufacturing, labor, and commodity power, but by control of global liquidity flows. Rather than suffer a hard internal reset, they chose to float the dollar, abandon gold, keep the economy going, export American labor and supply chains abroad, and maintain global dollar hegemony through soft financial power abroad.

Amongst other things, we spoke about this here:

Edward Luttwack notes the exhausted state of Britain, and its refusal to replace capital equipment in the wake of war, instead choosing more armament, here:

A great article on that:

![[Audio] What McKinley Understood that the Consultants Don't](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!K_zf!,w_140,h_140,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-video.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fvideo_upload%2Fpost%2F176351568%2Fad641dfe-5d78-47d3-b464-a9264de32018%2Ftranscoded-1760713381.png)

McKinley > McKinsey

One factor that gets overlooked in the rise of financialization; the aging of the population. The reality that some firms weren't going to make it and thus end private pensions for millions of workers led to looking for a different way to support them.