Houses Aren't Getting More Expensive, You're Getting Poorer

Reevaluating the Present Crisis

Thank you very much for reading and subscribing. Your attention and support make this publication possible. If you find this article valuable, it would be hugely helpful if you could like it by tapping the heart at the top of the page to like the article; that’s how the Substack algorithm knows to promote it. Thanks again!

Additionally, I recently polled some of the more engaged subscribers about what sort of content would be appreciated moving forward. A few things were clear. First, people like content on decolonization and the old world. Second, getting things in the afternoon tends to be appreciated. Third, people want more content, namely some shorter pieces throughout the week, in addition to the usual Friday long-form article. So, today I’m testing out my idea for that: instead of spending so much time on X (Twitter), where the algorithm constantly changes, I want to write shorter pieces on here that would be a thread there. This is the sort of article I am thinking about for that, albeit somewhat longer, so please let me know what you think!

A constant refrain is that houses are getting overly expensive. On a nominal cost basis, that is true. The prices of housing is ever-rising as immigrants pour into America and private funds like Blackstone and BlackRock buy up entire neighborhoods.1

This is a massive problem, as it has contributed significantly to the fertility crisis2: young couples generally don’t want to start a family until they own a home, but doing so is increasingly out of reach. That, in turn, means that family formation is indefinitely delayed, sometimes until it is too late and the fertility window has closed. Of course, there are many more problems than just the cost of housing, but it is a significant contributing factor.

And the cost has indeed marched ever upwards, with the cost of an average house nearly doubling in just the last decade and a half (going from around $220,000 in 2010 to $419,200 by the end of 2024) Here’s the data on that rise in cost provided by the St. Louis Federal Reserve:

The thing is, while the cost of housing has marched ever-upward when priced in fiat dollars, it hasn’t done so when priced in real terms, meaning when measured under a gold standard. In fact, when the cost of an average house is measured in ounces of gold, as it would have been for nearly all of history until Nixon took America off the gold standard completely in 1971, the cost of housing has actually gone down.

Listen to the audio version of this article here:

Why Measure in Terms of Gold?

That is important. While fiat is now the way in which we measure things, gold is a more stable unit of measurement that better shows what something truly “costs.” It is able to do so because “Over the long term, with balanced economic growth, the share of global production of gold remains constant.”3

For example, a nice men’s suit has cost about one ounce of gold for all of history, both in the present and going back to the Roman equivalent. Thus, the change in nominal value of ~$20 in 1900 to ~$2700 today shows how much inflation there has been: what would cost you $20 instead costs $2700, not because it costs more real resources, as represented by gold, but because the fiat currency has been inflated away over time. Whereas gold represents a constant fraction, the inflation of fiat means a given unit of it represents an ever-decreasing one.

So, when measuring the price of a house, it is useful to measure that good in terms of gold, as it shows what share of global production, or what real expenditure of resources, has to be spent on that house. The answer is that it’s about the same fraction of global production now as a century and a quarter ago. In fact, it’s somewhat less. So the real cost hasn’t gone up, as it has decreased when priced in ounces of gold. It is, instead, just the nominal number assigned to that cost that increased dramatically.

Back to Housing

The below chart from Goldmoney only goes through 2020, but is useful in showing the general trend: housing priced in dollars has marched on nearly inexorably, but when the gold standard is used for measurement, it has decreased somewhat.

That is remarkable. Over roughly the same period of time (from 1910 to 2016), the size of an average house increased by a remarkable 74%.4 Similarly, over that same general period, houses got noticeably more complex, with increased electrical wiring, plumbing, and the like. Admittedly, the materials of a century ago were somewhat better; plaster is sturdier than drywall.5 But, still, with labor costs increasing precipitously while houses got larger and more complex, you’d think the price would at least hold steady when measured in gold. Instead, it lessened noticeably.

To some extent, that makes sense. Housing is essentially a commodity,6 and a hallmark of a gold-measured system is that goods, whether commodities or finished goods, tend to either hold steady in price or get somewhat cheaper over time as we get better at making them.7 That stable price action occurs because, with the money stable, increased competence paired with innovation pushes the price of production down, whether shirts or shoes, houses or wheat.8 Even if such advances do not occur, stable money means prices generally hold stable, as in such a case, they represent broadly the same fraction of production.

This is why there was no inflation over the Victorian and Edwardian Eras, the heyday of the gold standard: the money was stable and so prices could, and did, hold steady or decline as innovation and improved methods of production came about over time. The below chart shows as much: the Victorian and Edwardian periods are noticeably free of inflation, with prices even declining somewhat over time, but the end of the gold standard and adoption of fiat with World War I brought with it sustained, high levels of inflation.

So, while we now have no gold standard, we can see what could have been: were our money still ounces of gold, housing would have gone noticeably down in price, not up. But, because it’s priced in fiat, the cost appears to have increased dramatically.

Below is a graph from the wonderful website “Longtermtrends” showing as much. Other than the post-Executive Order 6102 era (when FDR banned private ownership of gold), during which the price of gold was unnaturally suppressed, and the brief period around 2000, during which gold was noticeably undervalued, the price of housing measured in gold has decreased over time.

Why It Matters

This isn’t just chin-stroking. It does matter, as it shows the real problem with housing prices. The problem is not that, in real terms, they have gotten more expensive. They haven’t; the cost has gone down when viewed through the lens of gold, both during and after the days of the gold standard. The problem, rather, is that we have gotten poorer.

That’s not to say the rich have gotten poorer. They haven’t. Stocks have rapidly outpaced gold.9 Rather, the problem is that those living on wages rather than capital returns, which is to say nearly everyone, are being rapidly outpaced by inflation.

That is because those wages have not at all kept up with real inflation, the sort that’s hidden by CPI lies10 but put in stark relief by measuring price in terms of something real, gold, rather than government fiat. Measuring wages in gold is useful for the same reason measuring goods in gold is: the relative amount of gold received per hour of work over time shows what fraction of resources is earned by labor over that period, and in what way it is trending.

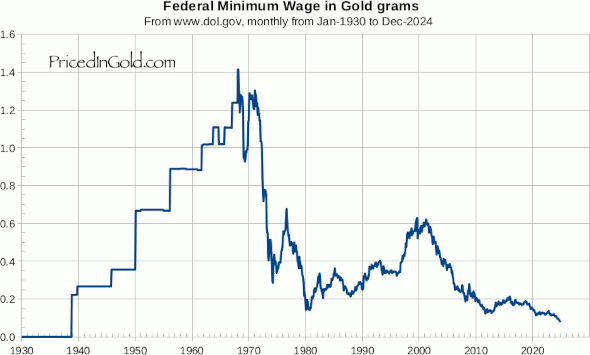

The gold story shows wages declining dramatically over time. In fact, with the exception of the period that began in 1933 with Order 610211 and ended in 1964 when President Johnson permitted the private ownership of gold certificates,12 during which time gold’s value was suppressed by government diktat, the story of wages is one of immense and continual decline, in real terms, against similarly persistent inflation. Here’s the value of an hour’s work at the bottom priced in gold over time:

Yes, fewer people make minimum wage now than was once the case. So, is the story any different in terms of average hourly employee earnings, including all income groups?

No. Rather, the problem is brought to even starker relief: it takes more hours now than it has at almost any other time for an average American worker to earn the constant fraction of global production represented by an ounce of gold. Put differently, the average employee is being paid less than ever, in real terms, for his work.

Forbes described this trend well in a 2013 article titled, “Measured In Gold, The Story Of American Wages Is An Ugly One.” In it, the author noted that CPI doesn’t tell the full story, but gold does, and that when priced in the real terms provided by gold, wages have fallen dramatically. As Forbes put it (emphasis added):13

By switching to gold, we can measure both wages and prices on an absolute scale—in ounces—and we can make precise comparisons. To convert the price of anything to gold, just divide the price by the current gold price. For example, in 2011 if a big-screen TV was $785, then divide that by the gold price of that year; the television set cost half an ounce of gold.

The bottom line is that, in terms of gold, wages have fallen by about 87 percent. To get a stronger sense of what that means, consider that back in 1965, the minimum wage was 71 ounces of gold per year. In 2011, the senior engineer earned the equivalent of 63 ounces in gold. So, measured in gold, we see that senior engineers now earn less than what unskilled laborers earned back in 1965.

That’s right: today’s highly skilled professional is making less in real, comparative terms than yesterday’s unskilled worker.

When measured in dollars, wages and prices appear to be rising and, comparing wages to prices, we see only a small loss of purchasing power. However, prices do not tell the whole story, because they reveal nothing about costs. Costs also fell and this explains why the apparent drop in the real wages seems small.

But measured in gold—and this is crucial to understanding why we need a gold standard—we see reality with clarity. Incomes are about one tenth what they were in the 60’s. Prices are down too, but not as much.

People who work for a living—those who produce every good and service—are being steadily and severely marginalized.

That last emphasized line is critical: “Incomes are about one tenth what they were in the 60’s. Prices are down too, but not as much.”

In other words, houses haven’t gotten more expensive. They’ve gotten somewhat cheaper, in real terms. But in those same real terms, as a constant fraction of global production, wages have fallen dramatically. They’ve gone from 1.4 grams of gold per hour for minimum wage at the height (current value ~$125), to under 0.1 grams ($7.25) now.

That then leads back to the problem with housing: whereas it has decreased somewhat in cost on the gold standard, wages have fallen off a cliff. Hence why the price of an average house is so high compared to the median wage. The average American is simply poorer now than his ancestors were, when real goods and wages are taken into account rather than CPI lies and nominal fiat numbers.

How to Fix It

That, in turn, leads to the other reason this matters: the problem is not simply that this situation exists but that the current calls for fixing it are wrong because they are rotten at the root, assuming as they do that the price of houses is the problem. That, as described above, is incorrect.

So, because it is incorrect, supposed solutions based on it likely are as well. Increasing housing supply, deregulating houses, and so on might help at the fringes. But probably not much. Even in Houston, one of the more deregulated housing markets, new builds for ranch homes start around $400k; at a certain point, the materials add up and building just costs what it costs.14 The fraction of global production can only get so low, in other words, as represented by the cost in ounces of gold.

Thus, pending a horrible, Black Death-style scenario in which population numbers fall off a cliff and housing falls in price as a result (something already happening in the underpopulated, rural regions of low-fertility rate countries like Spain and France), housing supply is not the issue and building more is too expensive to help. What, then, is the solution?

The data above points to two things: a stable currency and higher wages.

Wages

As for getting those higher wages, deportations of illegal immigrants would probably help, as would encouraging a return to two-parent households in which only one parent works. Much like there’s just a cost to things with building houses, there’s certain work that must get done, so limiting the labor supply by limiting who’s working and who’s in the country would help.

However, another important detail to remember is that, during the gold standard era: most people were self-employed. Wealth came not from wages, but from personal success, whether on the small scale of a farm, the medium scale of a shipping vessel or merchant’s shop, or the grand scale of an industrial enterprise. Those who made the money earned it by creating it; wages weren’t a path to wealth.

Now, only around 11% of people are self-employed, much in contrast to the 50% in 1900. That would indicate that, if you want to build wealth, actually building it rather than hoping the minimum wage rises to 1.4 grams of gold again is a smarter move.

Even with deportations and similar social changes that might lift the boot off the neck of wage earners, advances in technology are creating downward pressure on wages, particularly higher-wage jobs, and so creating wealth is a much safer bet than hoping to earn it.15

Stable Currency

The other matter is that we need a stable currency. Things improved during the Victorian Age because all classes could trust the money. Because they knew their gold standard currency would maintain its value, as indeed it did, they were comfortable saving it rather than investing it.

Those savings, generally bank deposits in amounts large and small, funded much of the latter part of the Industrial Revolution. Bankers could prudently direct the saved capital toward productive enterprises, and savers could count on their savings either holding steady or appreciating in value against the goods they hoped to buy, such as housing. They then used their savings to buy what the companies funded by their savings produced, creating a virtuous cycle that built the American economy into a behemoth.

Now the opposite is true.

Our money depreciates massively every year. Not only does inflation mean savings are constantly worth less, but the government lies about the rate at which that inflation is occurring (CPI is a lie), so it’s impossible to trust saved money not to evaporate over time or to know when that is happening and at what rate it is doing so. The money neither holds its value nor can be trusted.

Because saved money cannot be trusted, it is immediately directed into potentially imprudent investments. The bankers have to take riskier bets with what money is deposited, rather than acting in a more prudent and discerning manner. Would-be savers instead have to chase yield and return in an attempt to beat an unknown but still painful true inflation number, and often that money ends up contributing to and being destroyed in bubbles.

It is, in short, a mess. Further, it is not only a mess but very much the opposite of the virtuous cycle that once built the American economy into the envy of the world, a machine of prosperity and innovation. Instead, we see calcified companies, increasingly impoverished workers, and devastating market bubbles, as during the Tech Bubble or Great Financial Crisis.

A stable currency would fix that, or at least help in doing so. That’s what we had with the gold standard, and what we could have again with something similar. But a solution must come, for all the evidence points to the fact that we are getting poorer, not that things are actually getting more expensive.

If you found value in this article, please consider liking it using the button below, and upgrading to become a paid subscriber. That subscriber revenue supports the project and aids my attempts to share these important stories, and what they mean for you.

The CPI Lie: How the Government Hides the True Inflation Numbers to Escape the Effects of Its Own Spending

With Biden in the White House, inflation has been back in the news in a way it really hasn’t been since the days of Carter and the early years of the Reagan presidency. Prices are up, interest rates …

This is very good material and sound economic points. When you tie this to trade, immigration, and anti-trust (monopsony) policy, wages are greatly suppressed and gains transferred to a very concentrated class. Add in regulatory and government subsidies, prices for housing, healthcare, education all increase much faster than income. Balance sheets matter, two. Elizabeth Warren's Two-Income Trap does a decent job of talking about risk transfer as well. Usury or financialization is another problem. When one throws in the sexual revolution, birth control, abortions, and massive licit and illicit drugs flooding the market plus demoralization, it all adds up to an attack on the family and the Christian West. It appears to be an anti-Christian project meant to eliminate Christendom and properly ordered society. This is a world ruled by the spirit of anti-Christ.

Goldbuggery? Sold! There’s actually less of a historic spread between the S&P and BTC than you might think. Just scroll through the nonsense here and find the Guy Swann chart:

https://open.substack.com/pub/undergrounddesigns/p/win-underground-designs-btc