The Second White Rajah

The White Rajahs of Sarawak, Pt. III

Welcome back, and thanks for reading! Today’s article is another installment of the ongoing series on one of the most interesting colonial stories of all time: that of the White Rajahs of Sarawak, the three Englishmen who did what no other European ever accomplished and ruled as secure, legitimate, and independent sovereigns over an Oriental princedom. In Part I, I showed how James Brooke became a rajah. In Part II, I told the tale of how he secured his rule against existential threats from foreign and domestic industries. In this part, Part III, I’ll show you how his chosen successor—a nephew of his named Charles Brooke—turned the raj into a stunning success story. If you would like to listen to the audio version of htis article, you can do so via the Substack app, which provides a reading of it. As always, please like and share the article so the algorithm knows to promote it, and if you are not already a paid subscriber, please subscribe for just a few dollars to read the full story!

An oft-forgotten aspect of the Vanderbilt family’s rise to and fall from grace is that it wasn’t an immediate decline when the old Commodore died in 1877. No, his son William inherited 95% of the $100 million fortune—a fortune worth 1 out of every 20 dollars then in existence—and then doubled it.1 An astute steward of his family’s wealth, William managed to turn a gargantuan fortune even larger. It was after he died, when he chose to distribute the fortune equally rather than continue his father’s primogeniture decision, that it all fell apart, and the fortune was lost in a hazy cloud of cigar smoke and poor decisions.

The Brooke family—those romantic white rajahs in their sweltering little princedom—saw a similar second step, though one that was even more momentous. Charles, who had arrived in Sarawak as a young naval officer barely out of his teens and spent much of the rest of his life fighting pirates and cannibals, is the one who made Sarawak what Sir James had always wanted it to be.

He, as the second rajah, turned the princedom he inherited into a prosperous and thriving beacon of civilization in a land that otherwise would be under the thumb of the worst sort of crushing tyranny and poverty. He also expanded it dramatically, winning new lands that dramatically improved his economic and political position with both the sword and gold.

It is his story, one that perhaps lacks the romantic appeal of Sir James’s story but is just as magnificent in its details, that I’ll tell in this article.

As with Parts I and II, the four main books on which I relied are The White Rajahs by Steven Runciman and The White Rajahs of Sarawak by Robert Payne. I also consulted Empire, Incorporated: The Corporations That Built British Colonialism by Phillip Stern, which covers the Borneo Company Limited in some depth. That was helpful for this part of the story. In this article, I will refer to Charles Brooke as “Charles,” to distinguish him from his uncle, and each author by his last name. I am an Amazon affiliate, and will receive a small commission, at no cost to you, if you use these Amazon links above or others in the article.

The Second White Rajah of Sarawak

Unlike his uncle James, who was born in John Company’s Raj and indelibly stamped by it, Charles Brooke—born Charles, Anthoni Johnson—was born in the sleepy English town of Burnham-on-Sea, in Somerset. His father was a reverend, and his mother a sister of Sir James.

But while Charles lacked the birth in the mysterious Orient that had so shaped his history-altering uncle, they did have one base interest in common: the sea. Sir James learned to sail while briefly enrolled in boarding school, and it turned his eyes back to the East as a yacht-sailing explorer and conqueror in middle age; he also started an annual regatta that remains a beloved part of his legacy.2 Charles, eschewing the tradition of his uncles and brother as land-based officers, chose to serve in the Royal Navy after completing his education at Crewkerne Grammar School.

Interestingly, though he managed school a bit better than his uncle, he lacked his lifelong passion for learning: whereas Sir James built a 5000-book library stocked with all the best books on history, politics, and natural science in his Kuching palace, Charles never seemed much interested in a similar track. He instead occupied his spare time by reading French novels, and prided himself on speaking the French language…which he spoke abominably, reports claim.

The Rise of Charles

In any case, the waves beckoned to Charles Johnson, who set off in the Navy as a young man and served until 1852, when he landed in Sarawak as a man in his early 20s alongside his brother, Brooke, and took up a position as Resident at the Lundu station.

The two brothers had much to do, as the early 1850s were that bitter and dangerous era in which Sir James was fighting off a near-fatal case of smallpox from which his spirit never recovered, an official inquiry from the British government in which Parliament’s noxious liberals tried to ruin him, and a massive Chinese rebellion that destroyed Kuching and nearly ended the rajah’s rule.

It was that last incident in which Charles, then there for only five years, truly shone for the first time. Before then, he was just a competent member of the family who could fight headhunters and pirates with characteristic bravery and thoroughness, if proving a bit duller than his flashy and swaggering uncle (though also a much more able administrator). With the Liu Shan Bang’s rebellion, however, Charles rose to glory and distinguished himself as a leading man of Sarawak.

The Chinese Rebellion

As a reminder of what was covered in Part II, the incident that proved most serious in the life of Sir James Brooke was the Chinese rebellion. In fact, it almost ended his rule for good by killing him in his beloved, beautiful Kuching palace.

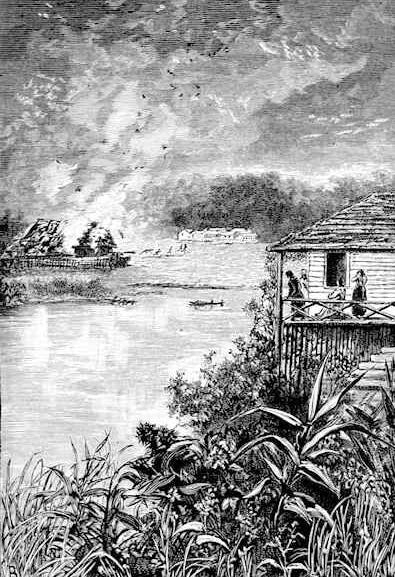

These Chinese immigrants, angered by years of what they saw as overtaxation and discriminatory policy, sailed from their inland gold mines and prosperous farms down the river to Kuching. A force thousands strong in hundreds of war canoes, the rajah’s forces in Kuching were no match for them and were quickly defeated. The fort was taken, the rajah’s palace burned, and the rapine started.

As the then-sick rajah swam through the murky river and flopped, exhausted, onto the mud bank to which he had escaped, the bloodthirsty rebels destroyed everything in sight. They tortured and killed Europeans. They burned houses and destroyed everything but the silver, which they stole. Acting like Oriental Vikings, they raped, looted, and burned before moving on like a plague of deadly locusts.

Sir James was almost broken by the rebellion. The Iban pirates sided with the already thousands-strong Chinese forces, adding more warfighting experience and deadly firepower to the rebellion that already outnumbered his forces and posed an existential threat. His Dyak allies were scattered, the already-small European population ravaged and decimated, the Royal Navy refusing to help because of the situation surrounding the Parliamentary inquiry. All could have been lost, and Sir James knew it.

And so he nearly gave up. Bemoaning his fate at his rule’s lowest point, Sir James retreated from the enemy with what small force he could muster and reportedly offered Sarawak to the nearby Dutch on “any terms,” if only they would put down the rebellion and end the anarchy while saving him and his men.

Charles put an end to that. Already respected—if not loved like his uncle—by the Dyaks, who appreciated his hardness and his ability, he rallied a force that could at least oppose the murderous rebels, if not defeat him. His exhortations, sternness, and vigor put the steel back into his uncle, and the white rajah resolved to fight, whatever the odds, against those who would destroy his patrimony and once again condemn the natives to lives of poverty and exploitation.

Led by Charles, the small force of exhausted Europeans and outnumbered Dyaks prepared to counter the ravages of the rebels, whatever the odds they faced. And then salvation in the form of a steamer appeared on the horizon and saved them: sailing up river in the well-armed, heavily defended ship to which the canoe-bound rebels had no answer, the rajah’s forces crushed the rebellion. They slew hundreds of rebels in their first counter-attack, then pushed onward for months to restore order and root the rebels out of their strongholds.

It was slogging, brutal combat in which little mercy was expected and less was granted as the rebels fought desperately against he who they would have overthrown and slain, and the taciturn Charles was the perfect man for the job. After crushing Liu Shan Bang’s Chinese rebels, he took the fight to the Iban and Bidayuh natives who had proved themselves so troublesome.

Finally ending the campaign with a momentous victory at Bau after months of grinding fighting in the sultry, inhospitable jungles, Charles and his native troops slew thousands of villagers and rebels opposed to the Brooke government. The rebellion was crushed in a sea of blood, and Charles had proved himself as a worthy relative of his uncle.

The Years of War

What followed for Charles was not a pat on the back and cushy job in Kuching, which he wouldn’t have wanted even had it been offered. Instead, he set out to finish the job his uncle had started and tromped into the even more inhospitable interior of Sarawak, where he would be the rajah’s emissary to the tribes, administer the rajah’s subjects and their economic endeavors, and try to crush what remained of the piracy and headhunting problem.

In theory, this sounds difficult: who wants to hunt headhunters through the tropical bush with an army of reformed headhunters at your back, all without nearly any of the modern medicines or conveniences of today? In practice, it was yet worse: Charles spent an incredible 16 years in the Sarawak uplands, fighting alongside the natives while also administering them for over a decade and a half with nearly no other Europeans in sight.

It is somewhat unknown what Charles did for those sixteen years. To be sure, he hunted pirates and headhunters while bringing pragmatic, Brooke-style administration to those unfortunate enough to live in the uplands of Sarawak. But little else is recorded as Charles, unlike his somewhat publicity-hound of an uncle, generally kept his thoughts and deeds to himself.

Already unforthcoming as a man before his sojourn into the Sarawak wilds, he became even more so as he tromped over tropical mountains and through steaming jungles for years on end with no companions but the little band of Dyaks he led. He didn’t go native in the Colonel Kurtz style, but he did become an even more taciturn and unyielding sort of man. Other than that, we know relatively little about what he was up to in the jungle.

While that might have made him an off-putting character to those Europeans who had the fortune to make his acquaintance during his years in the jungle, it proved to be for the better for his later rule. For over a decade and a half he had shared every triumph and misery with his band of Dyaks. He led them, fought by their side, and marched with them.

Further, he was nearly alone while in the uplands. He had to make decisions in war and administration that would do what was required of a European administrator or officer while not being noxious to the locals. A Sepoy Mutiny-style mass revolt caused by him, or even an 1857-style revolt against his leadership would have been the death of him, literally. There was no one to save him other than those affected by his decisions.

So, with life and death as an impetus, he came to understand the natives in a way that few other Europeans, perhaps even including his uncle, ever did.

Becoming the Next Rajah

What finally drew Charles out of the jungle was his brother. Specifically, it was his brother’s inability to rule.

As discussed in Part II, Sir James grew tired of Sarawak in the years after the Chinese rebellion. Embittered by Parliament’s treatment of him, shocked by the rebellion, and worn out by the tropical torpor and never-ending issues of his principality, he spent more and more time in England while letting his successor run Sarawak.

That chosen successor was, initially, his eldest nephew: Brooke Johnson, later known as Brooke Brooke (and called “Brooke” in this article). Brooke was in some ways an able man. He was brave in battle and a capable administrator, at least insofar as his uncle was. He was of the Brooke line, loyal, far more charming than his brother Charles, and able to win battles: he led the rajah’s forces to victory in the 1862 Battle off Mukah that dealt a serious defeat to the ever-troubles Illanuns pirates.3

But he was also possessed of some terrible traits that made him unfit to be a rajah. Namely, he was insecure in the extreme, and so when Sir James discovered he had an illegitimate son and sent the young man to Sarawak to serve in a minor administrative post, Brooke flew off the handle.

He accused his uncle of conspiring to strip him of his expected inheritance of becoming rajah of Sarawak, thought the young bastard had been sent to subvert him, and began a war of words with his uncle. That fight culminated in Brooke deserting his post as temporary rajah and sailing to England to argue it out with Sir James, at which point Charles was pulled out of the uplands and left in charge of Sarawak for the first time.4

Sir James, who previously was willing to tolerate Brooke’s shortcomings in the name of keeping the succession stable, was driven beyond fury by Brooke’s desertion of his post and dereliction of his duty in sailing for England. Angered to near madness, he stripped Brooke of his title, his responsibilities, and his position in an act of total reversal.

Though the two later reconciled their personal differences to some extent, Brooke was never again in a position of power in Sarawak. His time as rajah in waiting was over.

Such was Sir James’s decision, and it was final. But it was also one he could make because Charles had proven himself to be entirely competent as an administrator, military leader, and sovereign. Thus, in 1865, Charles was named the rajah’s successor (rajah mudha) and remained in his good graces for the next three years, until Sir James died in 1868 and Charles succeeded him as the white Rajah of Sarawak.

The Golden Rajah Rights the Ship

The situation Charles inherited in 1868 was not necessarily a promising one. The pirate problem remained under control, but was an issue nonetheless. Sarawak’s antimony was no longer much in demand, thus harming its ability to raise critically needed cash through exports. It had gained some territory to the north, but was at risk of being hemmed in as the Sultan of Brunei shed his territory. The Borneo Company Limited was in poor financial shape, and the rajah’s treasury was nearly empty. Sir James, after all, had died with a mere £1,000 to his name (around $190,000 USD in 2025), and was deeply in debt to the Borneo Company Ltd. Yet worse, the financial backer of Sarawak under Sir James, Baroness Burdett-Coutts, lost interest with his passing and refused to further bankroll the project.

Charles was able to right the ship and fix all of that, all while dramatically expanding his territory and turning Sarawak into an extremely wealthy principality.

Charles faced the problem from the start that, for the aforementioned reasons, he was in a poor position to do much, including recover. He had no money to use to develop opportunities there were, few possible ways to access any funds for that purpose, and had to continue waging fights against the pirates and headhunters despite the depleted exchequer. Turning that flounder ship around showed his administrative genius.

However, Charles did have a few small things going with him. One was that there was a great deal of natural wealth under his feet, from gold to oil. Second was that he had, in 1863, managed to conclude a peace with the Dyaks and the Kayans that left Sarawak "without an enemy in her dominions, and without an intertribal war of any description."5 Third, in 1864, his uncle had ensured that Britain finally appointed a Consul to Sarawak and recognised it, ending the tumultuous spat between the two states and ensuring Sarawak would be protected from foreign invasion into the future.

So, though there were pirates from without with which he would have to deal, he could at least focus his limited revenues and energy on “all the difficult and exacting work connected with the establishment of a stable government.”6

As his uncle was a relatively poor administrator, other than in terms of providing justice, establishing such a government would require a great deal. As The Spectator noted when looking back on his early days as the second rajah, “A revenue system had to be devised, a body of law framed, the machinery of justice put together and set in motion, and those multifarious matters considered and dealt with which relate to the public safety, health, and convenience.”7

Fortunately for Sarawak, Charles was the man who could accomplish that. Much different than his uncle, he was the sort of administrator who could generally ignore romantic notions and cut to the chase. He wasn’t indulgent with the natives, generally, but was fair and honest with them. He wasn’t a coward, but was also steady, managing to avoid the mess of oscillating between extreme bravery and black despair. He understood the natives without accommodating the worst of their vices. He was not loved, but was respected. As Runciman notes:

He asked for little more than that himself and found it hard to believe that any European should ever expect more. Like his uncle, he was without physical fear, but he was far cooler in an emergency, with a self-control that was akin to his austerity. His anger could easily be aroused, and it was all the more terrible for being restrained. His indulgence was reserved for the Sea Dyaks. He had no illusions about them. Of the Sea Dyaks of Lingga he says that they 'had that general and most disagreeable idea that white men only came into their country for the purpose of making them presents'. But he took the trouble to understand their customs and their outlook; and in his dealings with them he was scrupulously just. They could not deceive him nor corrupt him nor deflect him from his purpose. He could not arouse among the native tribes the almost romantic affection that followed Rajah James wherever he went. Charles inspired awe and admiration, which are, perhaps, a better basis for government.

It was on the basis of that character that he put the administration of Sarawak on a stable footing, ensuring over the next five decades that it steadily “advanced quietly along the road of moral and material progress.”8 Gone were the days of his uncle’s romanticism and poverty, in was his policy of ensuring stability and prosperity, though still without exploiting the natives. As The Spectator put it, “the heavier burden [was borne by Charles] and that, with talents not less remarkable than those of his uncle, he has carried out, in the face of the most serious obstacles, a policy of regeneration for which the striking exploits of Sir James Brooke merely paved the way.”9

Reforming Sarawak

A number of notable reforms characterized the rule of Rajah Charles, all of which were for the best in Sarawak and show his quality as a far-sighted, competent leader.