The White Rajahs of Sarawak, Part I

The White Man Who Actually Built a Kingdom in the Orient

Welcome back, and thanks for reading! This is Part I of a three-part series, and is an article I have been extremely excited to write for weeks, while putting in the many hours of research necessary for it. So I quite hope you enjoy it as much as I do. It is, I think, one of the greatest stories of the Victorian Age, as it quite captures what the era was about and what sort of men dominated it. Hence why it inspired books from Conrad’s Lord Jim to Frasier’s Flashman’s Lady. This is a post for paid subscribers, but I have left about half of the exciting bits of the story free to read, as I want people to know about the Brooke accomplishment. If you would like to read this in full (which really you should, it’s ~12,000 words of terrific adventure), please just become a paid subscriber for the cost of an overpriced coffee. Thanks again, and have fun reading!

What would you do if you inherited $5 million or so,1 lacked any desire to hold a steady job, and had a few years of military experience in the Orient? Would you enjoy drinking on the beach and wasting your life away in sloth? Buy a plot of land and become a gentleman farmer? Or, would you buy a yacht, slap some cannons on it, hire a cutlass-armed crew, and sail off in an attempt to conquer an exotic personal kingdom for yourself?

Sir James Brooke, the first of the white Rajas of Sarawak, got bored with the former and so decided to do the latter. In the process, he became not only a powerful king in the Orient who ruled over a vast swathe of land inhabited mainly by pirates, but one of the greatest heroes of a heroic age.

He, with never more than a few Europeans at his direct command and a couple of modern ships at his back, sailed into history by slaying pirates and established a dynasty that not only lasted a century, but perhaps could have lasted many decades more. In the process, he also pulled a savage people out of “nasty, brutish, and short” lives straight out of Hobbes’s Leviathan, turning what had been a tropical hell into a relative paradise.

Further, he was the only man to do so. No one else conquered an Eastern kingdom and became its royal, personally ruling over it. No one else from Europe became the personal king of an Oriental land and created a personal dynasty. Sir James Brooke not only did so, but also established a dynasty that lasted for over a century.

Further, he did so without engaging in all the tired and hated tactics of the British and Dutch East India Companies, from financial extortion to bad faith in agreements. Instead, he conquered his kingdom at the point of a beloved sword, with armies of feather-bedecked natives and musket-wielding Jack Tars behind him as he raced into history and turned a dismal land of mud, headhunters, and pirates into a thriving little land known for its beauty and prosperity.2 All that came thanks to his genius, initiative, and bravery. No one else could replicate it, and so he stands as a truly unique man of an already exceptional age.

In short, James Brooke achieved what no other man could. He achieved not only the life of a gentlemanly adventurer in the modern world, but the life of a self-made king, of a Westerner living as an enlightened Oriental despot. And not only did he achieve that momentous feat, but he bent the world enough to his will that future generations of Brookes lived out the same schoolboy’s dream.

So, here I’ll tell the story of how the Brooke dynasty of Sarawk started, and how it began turning a mud flat filled with murderous pirates into a prosperous kingdom. Sadly, the tale has been mostly forgotten, but it is really worth remembering. Let’s bring it back.

A note on names sources: The four main books on which I relied are White Rajah by Nigel Barley, The White Rajahs by Steven Runciman, The White Rajahs of Sarawak by Robert Payne, and The Life of Sir James Brooke by Spenser St. John. I will refer to each work by its author’s last name when citing it. In some cases, I have cited the works via footnotes (just click the note number if you want to read the relevant book section), and in others I have used block quotes. Runciman’s is by far the best, if you’d like to read more, and Payne’s is a close second. St. John was an intimate of Sir James Brooke, and his account is interesting for that reason. As the future rajahs of Sarawak were also named “Brooke,” in this article, I will refer to James Brooke as “James” so as not to confuse the story. I am an Amazon affiliate, and will receive a small commission, at no cost to you, if you use these Amazon links above or others in the article.

The Life of Sir James Brooke

The Education of a Rajah

The Exotic Orient, His Home

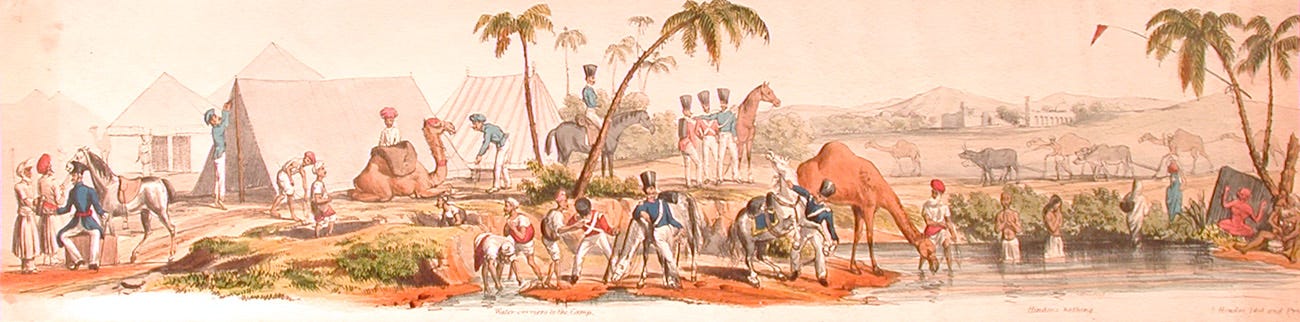

As with most great men, Sir James was a bit different from the time he was a young boy. Namely, James was born not at home in Merry Old England, but in Calcutta, then a part of the East India Company-controlled Raj.3 His father was a wealthy and genial but otherwise unremarkable judge in the Court of Appeal at Bareilly, also in the Raj, and his mother was the daughter of a Scottish peer.

It is important to remember that the world into which he was born was one that was very different from both the England of then and even the India of today. Then, apart from a few parts of cities in China and India, nearly the whole region was a land of heat-tinted adventure. It was a land of colorful costumes, exotic natives, splendorous courts, and baking heat.

In short, it was a stunning and dangerous world of cultural and sensory uniqueness that could not help but forever capture a unique spirit like James. As Payne tells it:

Those who have never been in the East have missed the better part of the earth. The sun is never so splendid as when it rises over the Eastern seas; the moon and stars are closer to us in the Eastern skies; the Eastern earth is warmer, richer, nobler-or so it seems to be. From Jerusalem eastward we enter a brighter and more intense world, where the people seem to belong to another universe small dark people with burning eyes and delicate skins. They are earthier than we are, and more spiritual; the fiery element has touched them; they move with a grace we can never equal. To live among them is to know a contentment unknown to the West; and sometimes a wanderer in the East comes closer to Paradise than anywhere on earth.

Today, the maharajahs have departed, but we still dream of them; and soon the sheiks will depart, but we shall dream of them for generations. There are no more diamonds in the mines of Anaconda; all the emeralds in the foreheads of Buddha have been plucked; the painted elephants no longer go in procession. The barbaric splendour of the East has been tamed. The Forbidden City in Peking has become a public garden, and the Living Buddha has crossed the mountain passes to the suburban comfort of an Indian hill-station. So it goes on, the legends rotting away and the mysteries explained. It is perhaps a pity.

So, James was born to the semi-mystical Orient and developed an affinity for the unique environment and great adventures within it, not to mention the vast opportunities an undeveloped world teeming with resources held, particularly to a man who brought it good governance.

But that was far in the future. For now, James was but a boy whose loving and wealthy family did what all others in their position did: sent him off to boarding school in England so that he might avoid slipping into an eternal torpor from the steaming heat (then thought to be a risk for children born in the Orient, particularly the kiln-like Raj) and obtain the liberal education necessary for a gentleman.

An Unbroken Spirit in a Very Tame Country

To say it didn’t go well would be an understatement. The young boy, then just 12 years old and away from the only home he had ever known, one quite different from East Anglia’s Norwich, where he ended up, struggled a great deal at Norwich School. He refused to learn, refused to listen, and eventually ran away.

Later legends emerged that he was a natural leader amongst the other grammar school boys. However, that appears to be untrue, and the school was happy to see him go when it kicked him out for having run away, with all his having learned in the interim was how to sail, something that soon became quite relevant to his life.

His loving parents were a bit more generous and understanding than most would have been. Winston Churchill’s parents, after all, foisted him on boarding school after boarding school to keep their troublsome son out of the house. Not James’s. His parents, instead, opted for an early retirement from John Company and travelled home to England, where they set up in the famous resort town of Bath and hired James a private tutor.

But the academic life was not one for the future rajah, and private tutoring largely proved a failure as well. Spenser St John, caustically describing James's childhood and lack of parent-enforced education in not just schooling but self-control, noted, “The want of regular training was of infinite disadvantage to young Brooke, who thus started life with little knowledge, and with no idea of self-control.”

With both boarding school and tutoring lacking any discernible salutary effects, the Brooke family decided that James would follow in the footsteps of his brother and become a soldier. So, in 1819, at just 16 years old. James was sent back to India as an ensign in John Company’s Bengal Army.

With a Saber in Service of John Company

It was in the service of the Bengal Army that the insouciant, unacademic boy began to shine. That’s not to say he was a particularly good officer. He wasn’t. The higher ranks found him inattentive to detail, and he once sent his sepoy troops marching off over the horizon just to see if they would do it. But he was brave and was willing to lead cavalry charges.

So, after six years of roasting in the sub-continent’s oven-like heat, James got to see his first action. That came with a fight near Assam during the First Anglo-Burmese War. Sadly for Brooke, just two days into the fighting, during which he was noted for his bravery, Brooke was seriously injured in either the groin or lung, with the former injury long suspected of being the reason why he never married, but also likely a myth.

In any case, he fell with a serious wound while leading a cavalry charge against a large force of Burmese soldiers and was almost left for dead. Fortunately, however, his commanding officer went to find him after the action and found Brooke was barely alive, saving him from bleeding to death on the dusty, unnamed field over which corporate and native armies were fighting.

The Young Rake about Town

The next five years were a period of convalescence for our young hero. Wherever he was hit, the musket ball had wrought serious damage and left him on death’s doorstep for numerous years. But, eventually, he was able to recover sufficiently to enjoy the social scene in his parents’ adopted home of Bath.

It was during this period that Brooke tried his hand at being a gentleman about town, the very sort of dashing young man in the pages of the Jane Austin novels4 he so enjoyed reading. He spent his days fox-hunting on horseback across the nearby fields, drinking with friends, and dancing in the town’s noted festivities.

Further, he got used to using his status as a wealthy young hero injured in a colonial war while attempting to romance young women, which it appears he did with some success. In 1833, in fact, he is alleged to have sired an illegitimate son by one such young woman. It was during this period that he appears to have cultivated his legendary social charm.

Similarly, not all his time up until then had been wasted. It was in his time as an adult in John Company’s service that Brooke learned how a nation in the Orient ought not be ruled, and his period of convalescence that exposed him to the heroics of Stamford Raffles, the heroic founder of Singapore, who also tried carving a state out of Indonesian territory.

Particularly notable was that James had time to sit and think about what he had seen in the mystical Orient. On one hand, he loved much of what he had seen from the colonial world as a whole, and had a sense that it was to the East he ought go if he was to grasp opportunity.

But, on the other, he grapsed that John Company rule was disastrous and generally characterized by misfeasance, malfeasance, and corruption. The size of the company-owned subcontinent was too large to run efficiently, officials generally lacked any sense of responsibility, and personal relationships were trampled under corporate interests.5 It was this experience that shaped his views on how to run his future kingdom.

Further, Barley notes that it was as James recovered at the tender hands of his parents in Bath that he read deeply about Stamford Raffles. Raffles, for reference, was the genius founder of Singapore and a man who attempted what Brooke was to accomplish—private rule of a Bornean kingdom. It was in reading about the exploits of Raffles that James appears to have connected the success that hero had in colonial undertakings to his own understanding of how to run a private kingdom.6

We know not exactly when the first germ of an idea about private kingship sprouted in James’s brain. However, it does appear to have been sometime in this period, thanks to the brilliant confluence of wound-induced sloth, wealth-induced tranquility, and inate love of and pull to the exotic region of his birth, that James recognized what he could accomplish if only he grasped the right vine of opportunity.

Particularly, the lack of vigor in his own life, the necessary time to pour over the life of Stamford Raffles, and the forced time to reflect on his experiences with the John Company government in India all combined, when paired with his childhood steeped in the wiles of the Orient, to create the idea of what became his destiny. At the very least, the basis of the idea was there and ready to germinate.

But, still, much of that remained in the future. In the present, James was drinking too much and doing too little, the classic recipe for falling into the very torpor his parents had hoped to avoid by sending him back to England for boarding school. Barley, describing Brooke’s sloth-induced foul mood and growing malaise, notes:

Meanwhile he moped at home, raging at ‘The growing, desperate, damned restraint - the consciousness of possessing energies and character, and the hopelessness of having ‘a fair field and no favour’ to employ them on... If I say that I fret or fume, the fools turn on me and say, ‘You have fine clothes and fine linen, and a soft bed and a good dinner,’ as if life consisted in dangling at a woman's petticoat and fiddling and dancing.

He shows all the signs of frustration: drinking too much, smoking too much. Despite his pampered condition, he feels himself one of the oppressed of this earth, with a horrible sense of time drifting away, and sees, staring him full in the face, 'a youth of folly and an age of cards'.

It was at this point that James, who was still suffering somewhat from the serious wound he had received at Assam five years prior, decided to try returning to the Bengal Army’s service regardless of it. To some extent, he was required to do so by time, as any officer who didn’t return to service within five years was cashiered on a small but fair pension.

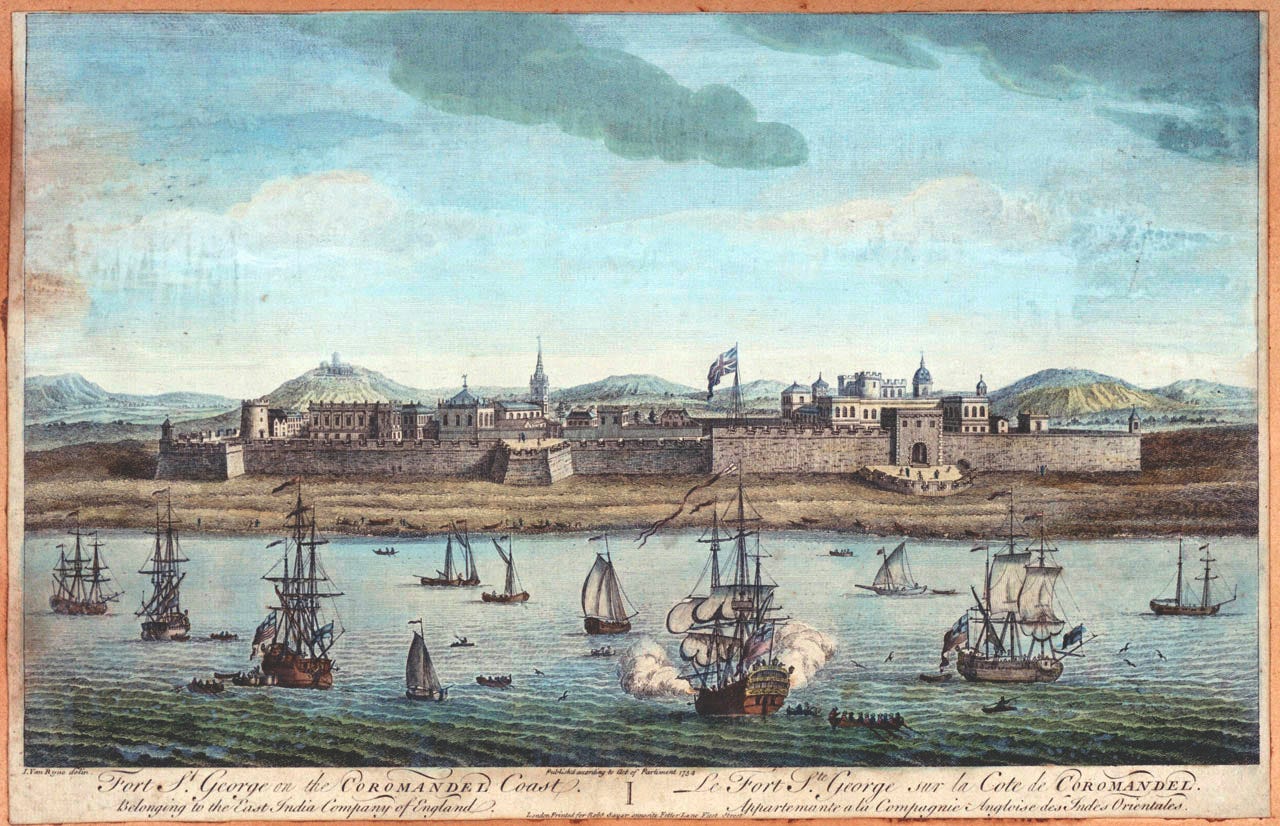

To Madras, and then the Heavenly Kingdom

So, James tried making his way back to John Company’s service. But in the age of sail, that was no small feat, and a combination of poor luck with the winds and shipping schedules, along with his own foot-dragging, retarded the journey enough that James arrived back in Madras with just days to spare.

However, the company refused to return him to service, as he would be unable to return to his unit within the strict five-year time limit, and so he resigned his commission and was out of the service of the despised British East India Company.

But James didn’t return straight home. Instead, he kept sailing on the ship that had taken him to Madras, the Castle Huntley, as it meandered its way to China by way of Singapore and from there to China. As he did so, he got to examine in closer detail the various races that people the Far East, particularly the Malays who were to characterize much of his later time as a rajah, and the Chinese expats who were to cause such immense problems far in the future.

Further, it was on this journey, in the context of his frustration with John Company’s senselessly unyielding rules and regulations, that whatever earlier ideas he might have had about empire-building in the undeveloped, unruled Orient burst forth. He sensed that a freer land could succeed in bringing prosperity, just rule, and European settlement to the Far East in a way that John Company's rule of the Raj never quite had. As Payne notes:

Already in embryo he was stating the ideas which were to ride him when he came to settle in the East. He wanted to see colonies growing freely, no longer at the mercy of the Company's Board of Directors in Leadenhall Street, with its niggling regulations. He wanted 'the care of a fostering government', meaning perhaps financial advances and the protection of His Majesty's ships. His colonizers were to be free citizens in communities where those who opened up the land would become possessors of it.

The time wasn’t quite yet ripe, and James sailed home to Bath. But the idea was there: a bit of brawn and a dash of good government could grant him control of vast swathes of Oriental land, and it could stand as an alternative to the thick-skulled mercantilism of the growingly superannuated and much-hated British East India Company.

Once home, James did everything in his power to convince his wealthy, experienced father to buy him a merchant ship in which he could take goods to China. That argument did not necessarily develop to his advantage for a long time. Namely, his father was hesitant to outlay any capital on such a project because he knew enough about his son to understand that he totally lacked any sense of business or care for the finer details, and would be a disaster as a trader. So, he refused the request repeatedly.

Eventually, however, enough badgering from not just James but also the womenfolk in the Brooke family led the patriarch to break down and buy him a small trading ship and goods with which to fill it. As could be expected, the attempted trading trip to China was a disaster and, after a semi-mutiny, James returned home to Bath after having taken a financial bath on his poorly informed merchant venture.

But, still, the allure of the mystical Orient called to him like a Siamese siren song, pulling his spirit back to the land where he could be a more successful Stamford Raffles, if only the next journey went a bit better. Thus, when his father died and left him £30,000 in 1835, James didn’t leave it “in the funds” and live a life of playboy’s ease.

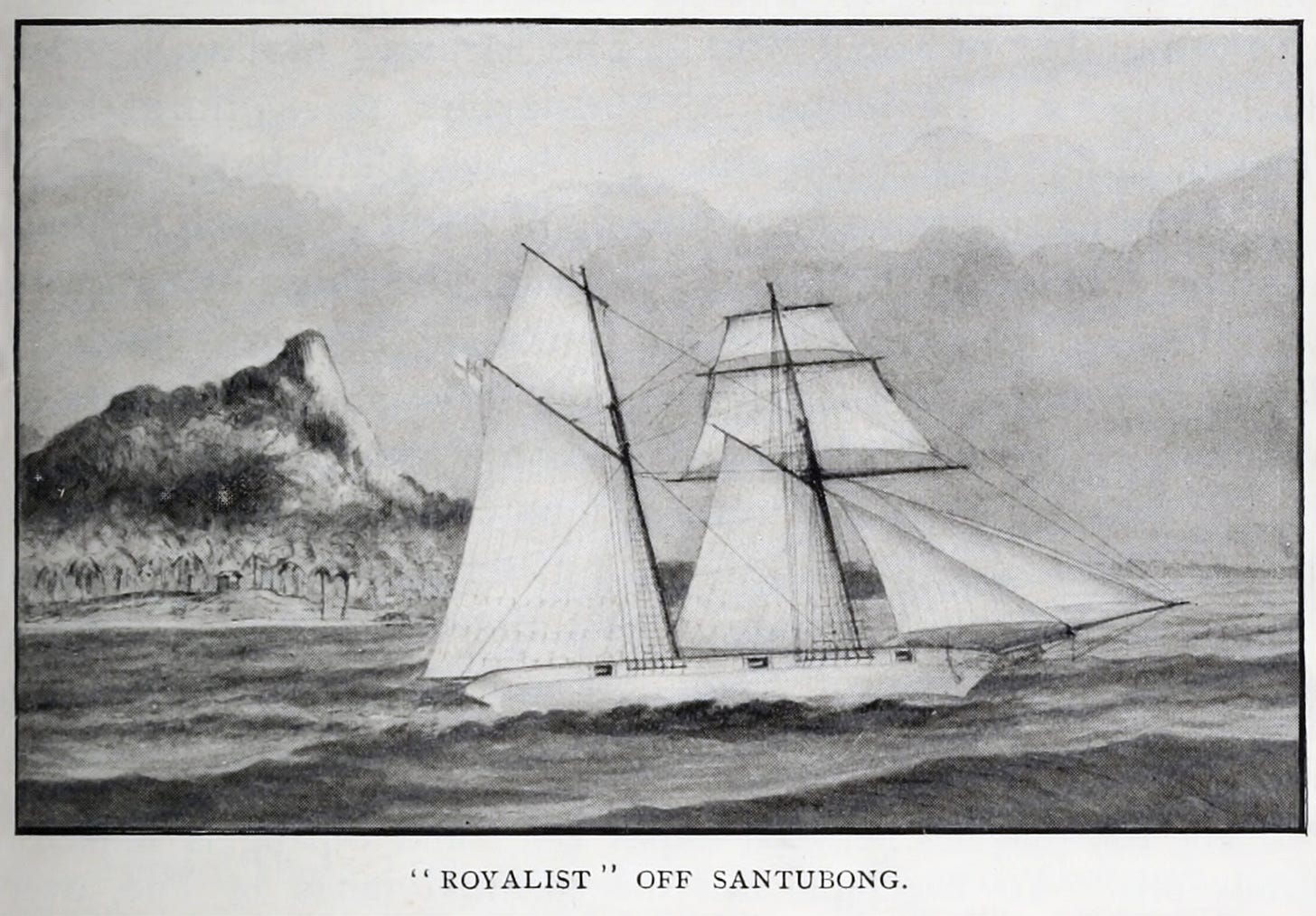

Instead, he decided it was time to raise the flag and go on an adventure back to the mysticism, exoticism, and sultry heat of those faraway lands. So, he purchased the Royalist, a Royal Yacht Squadron schooner that, because of its background, enabled him to carry arms and wear a semi-military uniform. With it, he sailed East and into history because his ambition demanded it of him.

Some sense of duty to the peoples of the benighted lands to which his yacht was headed drove him on across the waves. But it was also a sense of ambition, of a desire to prove himself through adventure. Writing much later on about what drove him to Sarawak, James wrote, “I was twenty years younger, and forty years lighter of heart when I left England for the shores of Borneo. I had some fortune, more ambition and no outlet for it. There are thousands and thousands of our countrymen whose hearts like mine are higher than their positions.”7

The Conquest of Sarawak

It is at this point that the Brooke family story changes. Whereas before James had been a somewhat interesting but otherwise unexceptional young gentleman, from this point on, he was something unique. It was an exceptional yet representative personification of the Victorian Age that he quickly became, doing so both with his mind and his musket, in true imperialist fashion.

He was no longer the drink-besotted playboy, the spendthrift son with delusions of grandeur, or even a dashing but imprudent cavalry officer. Instead, he was the personification of the civilizing mission, the man who brought peace to the natives and granted them just government by taking power out of their hands and leaving it in his.

His Oriental adventures began when he set sail for Indonesia—his chosen land of opportunity—and arrived in Brunei’s swampy, horrible-smelling town of Kuching in August of 1838. Opportunity beckoned from the first. Upon landing in the steaming town of mud and swamps, he found it engaged in trying and failing to put down a budding uprising against the nearby Sultan.

A Muddy Land of Surprising Opportunity for Wealth and the Civilizing Mission

But a mere adventure likely wouldn’t have held our young hero. He wanted to explore, yes, but also establish himself. Sarawak was the perfect place for such a roll of the dice, as in addition to finding a potential war—a potential ladder of opportunity—Brooke found a number of interesting things from a private imperialism angle in Kuching itself, and Sarawak generally.

For one, he found that the people were much in need of temporal and spiritual salvation. The Malays were Muslims who ruled the territory for their own benefit, and the Dyaks were splendorously decorated natives who either attempted to live lives of want in perpetually impoverished agricultural villages or go on the warpath as pirates. Further, all of the Dyaks were pagans whose favorite pasttime was hunting heads. As Payne tells it, describing the exotic headhunters James found:

These savages were the Dyaks of the forests and the river banks, who went about naked except for brightly coloured loincloths and helmets of plumes. They wore tigers' teeth in their ears, and decorated their long-houses with human heads which they hung up like garlands of flowers, filling the sockets of the eyes with sea shells. These Dyaks were ruled by Malay Sultans and Rajahs . . . [and] were handsome and unscrupulous.

That’s not all. Borneo generally, but the Sarawak region in particular, was swarming with pirates who preyed on native and European shipping. Some pirates were local Dyaks, others came in massive pirate galleys from as far away as the Philippines. Upon seeing the unscrupulous and predatory pirates in their massive war galleys, James understood that he’d haave an opportunity, over the next few years, to justify his rule in putting them down.8

That was all the more a shame as, were it not for the generally impotent nature of the local government, the land was a potential paradise for traders of the sort who made the colonial empires functional and prosperous. Particularly, the proven reserves of a type of ore called antimony, along with other natural resources like clay for pipes and timber, could be profitably bought for mere beads and velvet. James had little interest in trading, but understood the riches it might bring to his territory, were he to conquer it.9

And while the potential for trade solidified James’s understanding that the conquest of Sarawak might prove profitable in the long term, it was the chance to prove himself an adventurous gentleman by civilizing the natives that really captured his imagination. Further, he could do so while justifying his self-appointed mission in Christian terms acceptable to the British public. Naturally, he focused on the headhunters, pagans, and general lack of civilization, which therefore created a civilizing mission. As Barley notes:

Looking for a justification for British interference in terms of 'tender philanthropy', he homed in on the existence of slavery and paganism in the east. 'Not a single voice is upraised to relieve the darkness of Paganism, and the horrors of the eastern slave-trade.' He did not yet know about headhunting, whose eradication would later replace slavery as chief argument for the civilising nature of his mission. Once he was actually established in the east, the abolition of domestic slavery would be politically too hot to handle and he would leave it severely alone.

But had many opportunities to do so: it wasn’t just the pirates and headhunters who proved themselves to be an issue in need of correction.

Indeed, the local government proved itself to be awful and predatory in the extreme. As part of a long-practiced native custom, the local prince worked native laborers to death while mining antimony and confiscating all the Dyaks' property as part of an extortion scheme.10 Barley, describing the system of unjust expropriation that James later built his legitimacy by destroying, provides:

[The legal basis of the expropriation was the] serah which weighed particularly heavily on the Hill Dayaks, who had been driven into disaffection along with the Malays. According to this, Bruneian and Malay nobles and their relatives had the right to appropriate any Dayak property they took a fancy to . . . They could buy up forest produce at any price they saw fit, and if insufficient quantities were delivered by villagers they might seize their wives and children and sell them into slavery. Should they resist, other Dayaks would be set upon them - which might happen anyway, as part of the practice of issuing licences to devastate tribes beyond the reach of normal exploitation. This combination of practices had reduced the province to misery.

But while the local government was incompetent, ineffectual, and corrupt in the extreme, it was also friendly to British interests and acted as something other than the collection of piratical headhunters the rest of Borneo was known for. Instead of being either a vicious pirate or Stone Age headhunter, he was friendly to British interests and had rescued rather than preyed upon shipwrecked British sailors.11

And Rajah Hassim wasn’t just friendly. He was in desperate need of help if his little principality of Sarawak was to be kept out of the hands of a rival Malay leader. Further, he seemed to think the uniform-wearing, Royal Yacht Squadron schooner sailing James Brooke was a representative of some sort sent by the British government to help him out.12 This was particularly true as the Dutch had left Sarawak mostly unclaimed, so it stood to reason that the British might have an interest in the area. They hadn’t yet, but it was an understanding and situation that worked to James’s advantage.13

The First Battles, and Why the Natives Always Lost

James, of course, took full advantage of the opportunity offered by Rajah Hassim’s friendliness, predicament, and confusion. Further, it was this opportunity that gave James his sense of purpose. He wouldn’t just be a trader, or even just an explorer. He would become a warlord in Sarawak with an eye toward eventually ruling in place of Rajah Hassim.

And so he and his small crew of Europeans led the fight against the rebels Rajah Hassim needed aid in putting down, and in the process learned what it was like to fight in native wars…and what European tactics and morale could accomplish in such situations.

Particularly, they found that the Malays and Dyaks were extremely averse to taking casualties,14 and so if enough Europeans and well-led Dyaks could be gathered and hurled at the native-led troops in an assault, victory was assured. This lesson was to prove most helpful to James in the coming years.

Further, their refusal to fight in the open meant that the natives had a prediliction for building successions of wooden forts in the jungle, and war became a game of positioning and building. If the aforementioned European-led troops could be brought up to the fort, victory was essentially assured. All it took was the courage and leadership necessary to get them to a cannon-created breach in the ramparts.

Spenser St. John, describing that perplexing situation James found in the steamy Borneo jungle as he tried to battle Rajah Hassim’s enemies for the first time, noted that the native troops on both sides were terrified of actually fighting and so refused to come to blows with each other in a way that settled things. He says: