The Last of the White Rajahs

From Shirtsleeves to Shirtsleeves in Three Rajahs

Welcome back, and thanks for reading! Today’s article is another installment of the ongoing series on the White Rajahs of Sarawak, the three Englishmen who ruled part of Borneo for a century. In Part I, I showed how James Brooke became a rajah. In Part II, I told the tale of how he secured his rule against existential threats from foreign and domestic industries. In Part III, I told how Charles Brooke finally turned the raj into a stunning success story. Now, I’ll tell you how it ended in unnecessary disaster, much like the colonial world generally. If you would like to listen to the audio version of this article, you can do so via the Substack app, which provides an audio version. As always, please like and share the article so the algorithm knows to promote it, and if you are not already a paid subscriber, please subscribe for just a few dollars to read the full story!

There are no more White Rajahs of Sarasway today. While the Sultanate of Brunei not only survived the 20th century, but also came out of it incredibly enriched1 despite having sold off most of its territory before it began, the much stronger and more successful Sarawak is gone.

Now it is part of Malaysia, and is back to being ruled by the Malays whose duplicitous and extractive rule James and Charles Brooke had once brought an end to. Kuching is a major city. Sarawak is a prosperous territory. But the White Rajahs are gone, and so is the exotic splendour of what they once ruled.

So, what happened? How did the beloved, successful dynasty end?

Sadly, what happened across the colonial world2 happened in Sarawak too. A crisis of confidence in the idea that men like the Brookes should rule followed World War II, and so the projects that could have remained intact for the long haul—lands like Sarawak that could now shine even brighter than the Sultanate of Brunei, and with much more of an internal commitment to ordered liberty—were ended prematurely. Just as they began to flourish, they were ended forever.

What makes Sarawak’s story different, and all the sadder, is that it was purely by choice that the Era of the White Rajahs ended. The locals wanted them to stay. The British were ambivalent. The next in line to rule was more than ready to do his duty and govern Sarawak with prudence and an eye toward the liberty and prosperity of its residents.

But one man—Charles Vyner Brooke—and the few Wormtongues in his ears thought the project ought come to an end in the name of democracy and self-rule, and so the glorious project was ended and handed over to the British despite having survived the Second World War. Now all that’s left are the memories of better days, and the few relics of them.

As with Parts I and II, the four main books on which I relied are The White Rajahs by Steven Runciman and The White Rajahs of Sarawak by Robert Payne. In this article, I will refer to Charles Vyner Brooke as “Vyner,” to distinguish him from his father, and each author by his last name. I am an Amazon affiliate, and will receive a small commission, at no cost to you, if you use these Amazon links above or others in the article.

The Apex of the White Rajahs

When Vyner took over from his father, Charles, in 1917, it was far from clear that he would be the last white rajah. In fact, their rule was more secure and prosperous than ever, thanks to the decades of hard work by Charles to expand Sarawak’s territorial boundaries while bringing in responsible companies to exploit its natural resources in ways that benefited the native peoples of Sarawak.

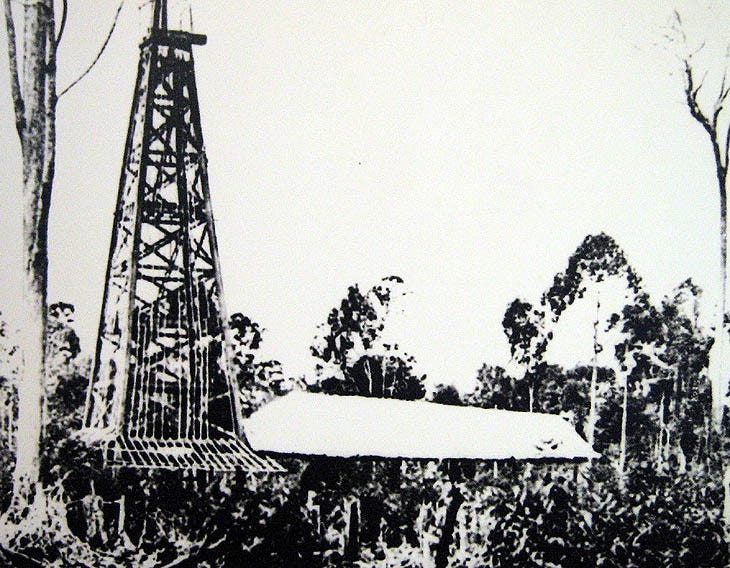

Enabled by Charles’s massive expansion of Sarawak’s territory, the Borneo Company mined huge quantities of gold, Chinese immigrants grew huge fields of pepper, and the Anglo-Saxon Oil Company developed the then-tremendously large oil fields of Miri.3

All of that meant that, by the time Vyner took the reins of power in 1917, his Sarawak was a very different place than the land of his grand-uncle, or even his father.

Sir James Brooke had died with barely a shilling to his name after years of fighting against bloodthirsty bands of pirates and headhunters. Charles’s first few decades of rule were spent eking out a living while fighting those same pirates and headhunters. Sarawak was an exotic Oriental land and being rajah had splendour attached to it, to be sure. But it was a far cry from even being a landed magnate in England, much less a prince or king. The revenues of the state were small, the demands on it high, the dangers severe, and the climate wearying.

By Vyner’s time, however, most of that was reversed. Particularly, the violence and state revenue situation had been rectified thanks to the foresight of Charles, and he could be relatively assured of neither needing to fight pirates and headhunters or find himself deeply in debt to a few companies and individuals. Instead, Sarawak was relatively safe and certainly self-sustaining.

The change in terms of violence was dramatic enough. In the old days, the Dyaks were always only one misstep away from going back to headhunting, and vast throngs of pirates showed up regularly to do battle first with the irregular forces of Sir James and later with the Sarawak Rangers.

The oil, gold, timber, rubber, and pepper revenues were turning Kuching into a thriving metropolis and filling the rajah’s coffers at an increasingly rapid clip. What had once been a state that would have died without small loans of a few thousand pounds to Sir James from Baroness Burdett-Coutts and the Borneo Company now drew revenues nearly as large as the Grosvenor family, the wealthiest in England.4

Further, unlike other colonies, it wasn’t a one-trick pony reliant upon a single cash crop or resource. Instead, it was built around a relatively dynamic (for the colonial world) of development, resource extraction, farming, and trade. Thus, by the late 1920s, Sarawak was exporting about £7,351,225 of goods a year.5 As Payne notes:

The depression at the end of the twenties hit Sarawak hard.

Happily, the exports of the country were sufficiently diversified to enable the country to survive. In 1929 exports amounted in Straits Settlements dollars to $63,000,000, and by 1932 they had dropped to $13,500,000. Just in time Sarawak pepper became established under its own name in the world markets, and while 19,000 piculs of pepper were sold in 1929, 71,000 piculs were sold in 1932. Gold exports also increased from $35,000 in 1929 to $400,000 in 1932. In Sarawak these dull figures were coloured with romance.

Though exports dropped somewhat during the Depression, they soon rose again, with the pepper crop and oil extraction growing dramatically and more than making up for the crash in rubber prices. Charles’s policy of spreading Sarawak’s economic base out widely, across all products in which it could compete well—from timber and pepper to oil and gold—paid off well as the Depression rooted speculation out of global markets and rubber prices crashed.6

All that is to say, Vyner—alongside his brother Bertram, with whom he shared some power per Charles’s wishes—was in a secure position.

World War One had only enriched Sarawak by dramatically increasing global demand for oil, and thus the prosperity of the Miri oil fields from which he drew substantial royalty revenues. He built on his father’s successes and immensely expanded development of the oil, rubber, and pepper industries of Sarawak. In so doing, he kept the state afloat when global economic calamity wiped away the fortunes and powers of lesser states and established men.

Things were going so well from a perspective of internal peace and order that he could even disband the Sarawak Rangers in 1932,7 a move that would have astounded Sir James or Charles, both of whom had spent most of their lives in merciless fights against pirates, rebels, and headhunters. Vyner, in contrast, could live in relative peace and prosperity even as the rest of the world underwent the turmoil of the Depression.

That was a dramatic change, almost beyond belief. Kuching and the lands surrounding it, the territory of the White Rajahs, had finally been transformed for the better. It wasn’t just that Kuching had gas streetlights,8 Sarawak had railways and paved roads (on which Vyner, much in contrast to his father, loved riding in a motorcar), and the Sarawak Exchequer reliable and large sources of revenue to fill it.

It was that the vision of Sir James Brooke—he who saw the faults of the British East India Company and wanted to run a state far better, for the benefit of the natives9—had finally come to real fruition. The land was prosperous, the people safe, the natives and immigrants alike flourishing, and the state on a stable basis. Further, all the vectors were in the right direction: things were continuing to get better, not stagnating.

Sadly, that was the apex of the rajah’s rule. Even out of those promising conditions, Vyner managed to fail in preserving his family’s rule once conditions turned against it.

Sarawak and the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere

While Sarawak prospered in the years after World War I, much of the rest of the world did poorly.

Particularly, even the victor powers in Europe faced significantly worsened material conditions—or at least the perception of them10—and so tried to foist disarmament on the world so as to rein in the military spending necessary to keep their empires alive. Meanwhile, Asia suffered too, though it was moving in a more rather than less militaristic direction that was directly hostile to the interests of the White Rajahs at the same time as Vyner lost faith in the century-old Brooke project.