McKinley Was the Best President Of the Twentieth Century

One of the Few Good Ones, In Fact

Welcome back, and thanks for reading! As promised, today’s article is a break from the past few weeks of focusing on South Africa. Because trade remains relevant, this will be the start of a series on a subject in which I remain quite interested—trade and the old American System—that I hope you will find interesting as well. As always, please make sure to tap the heart icon to like this article, as that is how Substack knows to promote it. Thanks again!

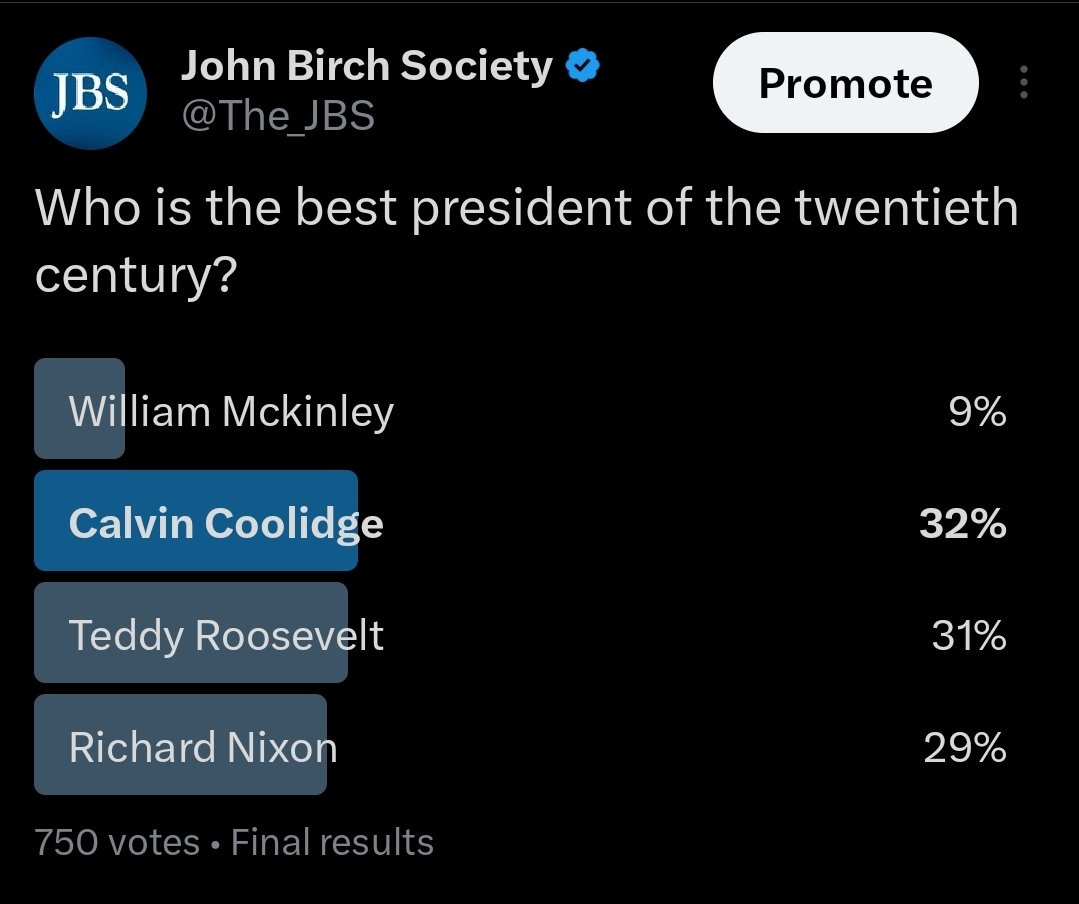

The John Birch Society is back with renewed vigor, and recently ran a poll on X in which it asked users who they thought was the best president of the Twentieth Century. Of the options—William McKinley, Calvin Coolidge, Teddy Roosevelt, and Richard Nixon—Coolidge won, with all the options except McKinley getting a reasonable share of votes. That is wrong, as my friend and repeat podcast guest Rowdy Yates pointed out,1 and shows a distinct misunderstanding of what happened in the disastrous Twentieth Century.2

What that poll shows is a fundamental misunderstanding of what situation America faced by the years leading up to the turn of the century, and how McKinley held off what Teddy embraced and Nixon was either unwilling or unable to change. Coolidge did indeed have many virtues as president, most notably his non-interventionist stance, but it was in following in McKinley’s footsteps and preserving Old America for a bit longer that he did so well, not in doing anything new.

To understand that, it’s important to understand what happened over the course of the Twentieth Century and how McKinley held it off as best he was able. First, I will explain that and how McKinley relates to it, then I’ll get into why he is so much better than the other options.

Listen to the audio version of this article here:

The Glorious Nineteenth and Disastrous Twentieth Centuries

As I have written about in my numerous past articles on President McKinley,3 the America he led faced a significant split in the road by the time the Nineteenth Century drew to a close.

On one hand, it was unbelievably prosperous, with the achievements of past generations having compounded to the point that America was increasingly the envy of the world. Compared to all others, our rail infrastructure was increasingly developed, our industrial sector the most innovative, our agricultural sector the most productive, and our citizenry relatively untaxed and unregulated compared to the other Great Powers, all of which taxed their citizens or subjects relatively heavily to pay for massive standing armies.

On the other hand, there was an increasingly serious threat that the America that had existed up until then was on its way out. While land was still cheap compared to in Europe, particularly England,4 our frontier was closed, and land was no longer free. Industrialization increasingly meant that America was a land of plutocratic business owners, bankers, and lifelong, wage-earning employees rather than yeoman farmers, large planters, and enterprising merchants. Further, the post-War Between the States Era increasingly saw the old, Friedrich List-derived5 American System of high tariffs powering domestic industry and domestic infrastructure investment phased out6 in favor of a British-style system of less-protected trade.7 And, of course, the 1860s saw nationwide bloodletting on a vast scale as the issue of slavery was settled by the sword, with much bad feeling coming as a result.

The damage done to the American psyche by that turmoil was immense.

Sectional antagonism had long been an issue, but the vast bloodletting of the war aggravated it, and the fight over Reconstruction made it all the worse. Thus, as years of turmoil followed years of violence the like of which America has never again seen on even a nominal, much less per capita, basis, it remained unclear if America could ever be a united nation again.8

As Frederick Jackson Turner noted in his superb The Frontier in American History, a collection of essays around the topic of how having an open frontier had shaped the American mind and development, most notably our political system, it was unclear if the American spirit could survive the closing of the frontier. As he put it in The Significance of the Frontier in American History, the essay that inspired the book, "American democracy was born of no theorist's dream; it was not carried in the Susan Constant to Virginia, nor in the Mayflower to Plymouth. It came out of the American forest, and it gained new strength each time it touched a new frontier." It became unclear then, if America’s political system could survive the death of a frontier wilderness upon which its energies could crash. Could the “vital force” once behind America survive if there was no longer a wilderness into which it spend its energies winning and transforming? Such remained to be seen.

Adding to the perplexity of the moment was that the non-frontier aspects of American life were shifting as well. Sleepy towns and yeoman or planter-owned farms, whether in the steamy South, Yankee North, or newly-settled Midwest, were giving way to polluting, smoke-spewing factories and vast centers of bleak urban sprawl characterized mainly by impoverished migrants, crime, and grime. No longer were Heritage American gentlemen of the old Virginia gentry in charge; instead, mob bosses like Boss Tweed turned urban corruption into an art form as plutocratic factory owners squeezed every drop of effort and profit out of their broken, imported employees. The end of the frontier, in short, meant not investment in Jefferson’s Arcadia but rather increasingly inescapable industrial life reminiscent more of Dante’s Inferno.9

In short, America was increasingly looking like a nation irreparably harmed for the worse by the changes inflicted upon her. Massive waves of immigration crashed upon our shores, now with no frontier to settle and become Americans upon. Industrialists were squeezed by falling tariff rates, and in turn, squeezed their workers to recoup those lost profits. Settled life became required as the formerly free frontier land dried up, and that settled life meant one of lifelong industrial servitude and all its indignities, such as competing with ever-more numerous migrants, rather than the independent life of a yeoman farmer. Meanwhile, increasingly rigid ideological adherence to the gold standard meant deflation that harmed small farmers the most, throwing yet more formerly independent Americans into the gaping maw of eternal employment.

As could be expected, those changes did what Turner suspected they might: they reordered our political system away from the old disagreement of states’ rights vs. the national government to a bitter fight between increasingly socialistic populists and increasingly plutocratic Establishment figures. Coming alongside that fight was one between labor and capital, with incidents like the Haymarket Riot10 and Homestead Strike battle11 turning violent, and the Great Upheaval12 creating fears of a Paris Commune-style socialist revolution13, which up until that point had been a non-issue in America.

McKinley’s Relevance and Accomplishments

It was President McKinley who fixed those issues, at least well enough to keep America a somewhat recognizable country.

Particularly, it was his willingness to fight over the issue of tariffs and push for a return to the American System in a way that helped workers while preserving private property that deflated fears of revolution, and it was his unleashing of American might on Spain and redirection of our adventurous energies outward that gave America a replacement abroad for the frontier.

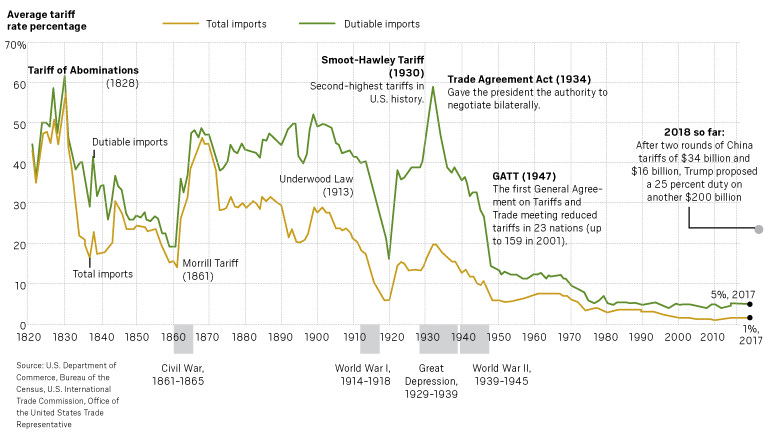

McKinley and the Tariff

McKinley’s view on tariffs was clear: much unlike President Cleveland, he saw them not as a corrupt and temporary evil that had to be done away with eventually in the name of supposedly moral free trade, but rather an unvarnished good that encouraged American excellence. As he put it in 1890 when fighting for the famous McKinley Tariff that reversed the trend of declining tariff rates, “We lead all nations in agriculture; we lead all nations in mining; we lead all nations in manufacturing. These are the trophies which we bring after twenty-nine years of a protective tariff.”

Key there is the idea that American industry, and the agricultural and resource extraction industries that supported it, required protection to thrive in the way it did. Competition with nations abroad, as was clearly shown in the late 19th and early 20th centuries by Great Britain,14 didn’t mean national flourishing through lower prices, but rather non-existent profits and lower wages that immiserated both capital and labor. Mass migration in such an environment only added to the workers’ woes, as it meant scarcer work and thus lower wages.

That might be appealing to certain plutocrats, but it was a very un-American idea. As Benjamin Franklin had put it a century prior to McKinley, describing the virtuous cycle of high wages and protected profits, “High wages attract the most skillful and most industrious workmen. Thus the article is better made; it sells better; and in this way, the employer makes a greater profit, than he could do by diminishing the pay of the workmen. A good workman spoils fewer tools, wastes less material, and works faster, than one of inferior skill; and thus the profits of the manufacturer are increased still more.”15

It was that state of things which McKinley attempted to rectify with his tariff of 1890 and later adjustments to it, most of which re-raised the rates that Cleveland lowered. High tariffs meant high profits, and high profits meant high wages and innovation. In short, he balanced the needs of labor and capital in a way that proved salutary to both.16

McKinley and Tensions

Through the tariff and a willingness to work with both labor and capital, McKinley managed to deflate the growing sentiment of hostility between workers and employers in the country, particularly in the industrial and mining sectors.17 The higher real wages seen with the tariff, his obvious concern for the standard of living of American working men, his non-hostility to capital, limitations on wage-depressing Chinese economic migration, and his positive vision of American excellence in the present and future all combined to help him avoid the catastrophe of a socialist revolution, or even socialist movement, of the sort that plagued Europe. Instead, America got a revival of national prosperity and received it in a somewhat more generalized way, which in turn meant significantly lowered tensions between labor and capital.18

Further, despite having served as a Union officer in the war, he encouraged reconciliation between North and South. He built monuments to the Southern dead, encouraged Southerners to join America in its next step forward by volunteering to fight the Spaniards (which they did in great numbers), and generally refused to “wave the bloody shirt” and denigrate the South to rile up his Republican base. Altogether, that meant he managed to bring the South largely back into the fold of American society and heal the division that came from war and Reconstruction.19

So, by being non-hostile to the various sides of America’s biggest social battles, namely the formerly budding labor-capital war and the remaining North-South split, McKinley got them to appraise his policies honestly. By then enacting policies that aided and encouraged everyone, from the heightened tariff to the monuments to Confederate war dead, he further won and used their trust to deflate bubbles of anger that could have popped at any time and led to disaster.

McKinley and Stability

In avoiding any sort of revolution or major unrest, President McKinley also preserved and enabled stability in America of a sort sorely lacking in Europe. Yes, we had an anarchist movement, and it eventually killed him, but it and our minuscule socialist movement were of little import compared to the French and Russian anarchist woes. “Our” anarchists were largely imported immigrants from Eastern Europe with little connection to or love of America, and so could be deported when the time came. Actual American workers were largely of far less radical political beliefs, which meant they could be worked with rather than fought against.

This was even true of the gold-silver spat, with William Jennings Bryan leading an increasingly populist Democratic Party against McKinley. That situation could have been dangerous, and McKinley, never an ideological goldbug, could have given in and devalued the currency by remonetizing silver, something that would have had major financial repercussions, particularly with gold standard-committed Europe. Instead, having bought himself time with the tariffs, he was saved by the discovery of the Rand mines in South Africa, which poured out gold and loosened up monetary conditions without requiring an end to the gold standard.20 Bryan’s silver movement then deflated on its own accord, and America retained its stability-encouraging, in terms of prices and international agreements for debt and business, gold standard.

Finally, McKinley redirected American settlement energy outwards. Yes, our frontier was closed, and the transcontinental railroads meant it was increasingly populated. That could have been a problem, as countries full of young men rarely do well without a war or escape valve. McKinley’s engagement with the wider world,21 whether via the Spanish-American War, the Annexation of Hawaii, the building of the Panama Canal, or all resultant opportunities for adventure (whether of the military, imperial, or business sort) abroad, changed that. Yes, that was no frontier. But an America engaged abroad meant that men of talent and agency, such as a young Herbert Hoover,22 had the opportunities to go on business adventures around the world if they so desired, as did those who got involved militarily by joining the Rough Riders for a short stint of adventure or Marines and Navy for a longer one. Thus were young men given opportunities to do something adventurous, glorious, or both, though the frontier on which their ancestors made those same exploits was closed.

McKinley Altogether

What President McKinley represents, then, is a rejuvenation of America of the sort it very much needed. Whether deflating the inflated hatreds of labor and capital or redirecting adventure-minded young men abroad, encouraging domestic economic expansion or reconciling North and South, he bridged the gap between the America that had existed, one many wanted to continue existing, and what was possible in an age of industrialization. That was no small feat, and it very much benefited America.

No other president who followed did so in the same way, including all of the choices laid out by the John Birch Society’s post.

McKinley’s Superiority

Calvin Coolidge

The winner of the poll, and man probably closest to McKinley in terms of salutary actions, is Calvin Coolidge. He was generally a non-interventionist who believed “the business of America is business,” and as such trimmed what detritus of Wilsonian tyranny he was able, though generally in degree rather than kind. The income tax remained, for example, but was cut significantly.23

In addition to cutting taxes, he, much like McKinley, spurred massive economic growth that, in turn, meant higher wages without overly much inflation, and thus a higher standard of living.24 He did so alongside tariffs that were lower than those of McKinley but still high compared to Wilson or the Cold War, which in turn promoted further domestic prosperity. Adding to that was his Immigration Act of 1924, which severely curtailed immigration from Asia and Central and Eastern Europe, thus lessening both the problem of anarchism and of wage depression.25

But despite being better than socialist tyrants like Wilson or FDR, Coolidge was no McKinley.

For one, despite generally being something of a non-interventionist, he wasn’t willing to wholly reject the increasing bonds between the federal government and Big Business that his recent predecessors, namely Wilson, had established. One example of this was the Federal Oil Conservation Board, which led to the national government deciding how to “stabilize” the oil industry.26 McKinley just let survival of the fittest rule, and it was Rockefeller’s Standard Oil that stabilized the industry while providing a superior product to consumers, at no cost to the taxpayers and without creating abounding opportunities for corruption. Coolidge was unwilling to take so momentous a step as returning to that prior era of economic freedom, and so he did otherwise.

Similarly, Coolidge was unwilling to do away with the abominable income tax. Despite past generations seeing it as an unbearable form of tyranny, the income tax was made law via constitutional amendment in 1913 after being temporarily enacted as a wartime measure by Lincoln. Coolidge could have followed in the footsteps of McKinley and used a heightened tariff to obviate the revenue issue while getting rid of the income tax, perhaps even pushing for a repeal of the amendment. Instead, he went along with the Revenue Act of 1924,27 which merely cut the income tax rate while keeping it intact, enabling the later, nearly 100% rates seen under FDR. Further, it kept the top rate at an absurd 46% and both created a new gift tax while also raising the death tax, both of which serve to sever connections with the past and discourage investment in the future.28

Then there was the Washington Naval Treaty.29 While McKinley encouraged American strength and got America involved with the world in a way that promoted opportunities abroad, Coolidge went along with a treaty that limited our ability to project power into our territories or even fortify bases in the Pacific, setting America up for the early years of disaster fighting Japan. Yes, it was Harding rather than McKinley that began the treaty negotiations, but McKinley went along with it rather than rejecting it, which quite harmed America in the long run.

Overall, then, Coolidge showed generally the right instincts and views, but an unwillingness to go to the dramatic lengths necessary to achieve them. McKinley’s Tariff of 1890 was a major rejection and repudiation of the direction American trade policy had been heading in, much as his working with both labor and capital, or willingness to reconcile with the South, were sea changes in national policy. Coolidge, in contrast, was willing to change policies in degree but not in kind, thus setting America up for the disaster it saw when FDR took advantage of what avenues for tyranny remained thanks to Coolidge, namely state control of business decisions and high income and death taxation.

That doesn’t mean he was a bad president while in office. He oversaw a great flourishing in American prosperity that was caused in large part by his tax cuts, tariff policies, and the like. But in being unwilling to make the massive changes he seemingly saw needed to be made but would have been difficult to achieve, he helped inflict quite a bit of damage on America.

Teddy Roosevelt

While not a tyrant, quite unlike his cousin FDR, Teddy Roosevelt was a problem for America in both his vanity and his policies toward business.

For one, it was Teddy’s vanity-induced decision to be a third-party candidate in 1912 that torpedoed President Taft’s attempt at re-election and thus put Woodrow Wilson in power.30 Woodrow Wilson was an utter tyrant31 who demolished much of the America that McKinley had done so much to restore, namely the sort of prosperity, liberty, and freedom from turmoil that came with a protected economy that was almost untaxed except for tariffs and nearly unregulated. Wilson gave us the income tax and, during WWI, state control over business, destroying all of that, and Teddy put him in a position to do it.

Even more importantly, and much more directly, the roots of the regulatory state that have done so much to stifle American prosperity and create class conflict lie with Teddy.

Particularly, in the belief that “good trusts” and “bad trusts,” with trusts effectively being the multi-state corporation of the day, could and should be brought into line by the government, with the “bad” ones destroyed.32 In some ways, that was justified, as it is the preserve of the national government to punish fraudulent, abusive, or otherwise illegal behavior that occurs across state lines. But, importantly, that wasn’t the extent of Teddy’s ambitions. Wielding the Sherman Antitrust Act like a club,33 he smashed various successful businesses, most notably Standard Oil, merely because they were big. That not only diminished business confidence, and thus prosperity, but also led to the great evil under which we burden today: national government regulation of minutiae for the mere sake of it. Teddy legitimized that by acting severely upon the idea that he could and should, as executive, regulate everything. As one of his biographers put it, "Even his friends occasionally wondered whether there wasn't any custom or practice too minor for him to try to regulate, update or otherwise improve."34 That is what the regulatory state of today does, with the regulatory state costing somewhere around $2 trillion a year in 2023 terms,35 or somewhere around 7% of that year’s GDP. For that, we have TR to thank, and it is very much the opposite of what McKinley did.

Further, his regulatory, anti-business policies appear to have created the 1907 panic,36 which not only retarded national prosperity, but led to increasingly vituperative class warfare rhetoric from him. At one point during the panic, for example, he blamed the wealthy for the panic and praised his own anti-business decisions, saying, “It may well be that the determination of the government...to punish certain malefactors of great wealth, has been responsible for something of the trouble; at least to the extent of having caused these men to combine to bring about as much financial stress as possible, in order to discredit the policy of the government and thereby secure a reversal of that policy, so that they may enjoy unmolested the fruits of their own evil-doing.” That is the opposite of McKinley’s pragmatic process of working with both labor and capital to avoid dangerous confrontation and create positive, generalized prosperity. It is, rather, class warfare rhetoric of the sort that leads to anarchism, socialism, and disaster, as eventually it did in the coming decades. Further, it was self-destructive in that it further encouraged the wealthy to do anything other than invest in America, which is what was needed to get America out of the recession.

That’s not to say Teddy had no virtues. Quite the opposite is true. His time as a cowboy (and more importantly, promotion of that time) did a tremendous job in keeping the frontier spirit alive even as the frontier closed. He remained a resolute defender of tariffs, as shown by both his general refusal to change the McKinley tariffs37 and his comment that “pernicious indulgence in the doctrine of free trade seems inevitably to produce fatty degeneration of the moral fiber.”38 And, of course, his foreign policy built upon McKinley’s quite well.39

But on the whole, Teddy’s legacy isn’t unstained. It is he who legitimized the idea that ill-informed popular discontent, which in other words is merely the mob, is enough to justify government involvement in business affairs past the point of merely protecting Americans from fraud, abuse, and the like. There was a legitimate basis for initiatives of his like the Meat Inspection Act and Pure Food and Drug Act40—poisoning food purchasers and hiding dangerous chemicals in their groceries isn’t legitimate business activity. But Standard Oil merely refined oil well and provided a high-quality product to those who wished to buy it,41 with its market share falling in the years leading up to its Teddy-led dissolution. The legacy of that, which is that a business can be destroyed merely because the executive wishes it so, has been a terrible one and led to immense abuses by the regulatory state.

Nixon

I have far fewer positive things to say about Nixon than the other men. Pat Buchan’s book on him, The Greatest Comeback, is reasonably good and shows Nixon’s generally good character in his personal life and the fact that he detested communism. That is good, as is the fact that he helped Whittaker Chambers expose Alger Hiss, as is described in Witness. Further, Nixon helped build a geographic and demographic base that the GOP could use to win elections again,42 as eventually happened with Reagan — blue collar whites in the Midwest and Southern whites could be a basis for victory on a reasonable platform, and Nixon helped prove that.

But other than that, Nixon was terrible in comparison to McKinley.

For one, he took us fully off the gold standard, which not only led to immense inflation and immiseration in the following years, but also created a recession, while also being a basis for yet more government regulation and control over the economy.43 Perhaps that had to happen, given the monetary situation at the time, but it was a disaster nonetheless and one over which he presided.

Then there were the Cold War struggles over which he presided.

Most notably, there was the Vietnam War, and he ran for office on the pledge of having a “secret plan” to end the war. He didn’t have a plan. None whatsoever. “Vietnamization” was forced upon the military under Nixon because of how poorly the war appeared to going. The invasion of Cambodia destabilized the country and gave the Khmer Rouge the upper hand. The only plan he did have was sabotaging LBJ’s already humiliating peace negotiations with the North Vietnamese, which just postponed defeat and led to tens upon tens of thousands more casualties. The Vietnam War: A Military History by Geoffrey Wawro, despite being flawed in many respects, shows as much in crystal clear relief.

Then there was the conflict about which I deeply care: The Rhodesian Bush War. Despite being a clear case of a free Western country fighting communism, America not only failed to come to Rhodesia’s aid, but actively aided the communist terrorists.44 As Ian Smith recounts in painful detail in The Great Betrayal, the Rhodesians desperately thought that, with Nixon in the White House instead of LBJ the Civil Rights socialist, America might back off of destroying them. Instead, Janus-faced Kissinger pretended to be on their side while secretly aiding in its destruction.45 Final defeat was staved off until Carter,46 but it is in part because of Nixon’s monumental betrayal of their hopes that the Rhodesians gave in rather than try to hold out until Reagan, and in any case he and Kissinger weakened them severely.

There’s much more wrong with Nixon, though Watergate is overblown and the EPA was more of a formalization of existing state level EPAs rather than anything new, but those are representative examples of his utter failure as a president. Real America held out until him on the hope that a conservative president would prove to be something different than FDR and the “New Deal” state that came with him, much as Americans had once hoped Coolidge would be a repudiation of Wilsonianism. Instead, they got the same sort of flailing, Big Government policy. Sky high taxes, ever-increasing levels of regulation, and foreign policy decisions that aided the communists characterized his administration as much as the others that preceded it.

![Taxing The Rich: The Evolution Of America's Marginal Income Tax Rate [Infographic] Taxing The Rich: The Evolution Of America's Marginal Income Tax Rate [Infographic]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!b8MH!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F7e56aff3-2f76-4b1b-b1a8-29e1fba6bf4b_1600x900.jpeg)

Whereas McKinley empowered American prosperity with nearly non-existent direct taxes, high tariffs, and all the rest, Nixon did quite the opposite and embarrassed America abroad while making a fool of himself at home.

McKinley Was By Far the Best of the Bunch

The sad fact is that the Twentieth Century was a disaster for America, particularly if one’s conception of America is the old system that the Founders would have recognized.

There were, by that reckoning, perhaps a handful of presidents who fit the bill. Harding and Coolidge were at least okay, and Teddy Roosevelt had many redeeming characteristics while Reagan reversed some of the worst of the tax decisions the earlier presidents made. GW Bush and Clinton further did that, but only while destroying American industry via globalization, which was far worse than the marginally higher taxes that preceded them were bad.

Of all the presidents, McKinley by far stands out as a man head and shoulders above the rest. He helped build American prosperity, defended American industry, led to a rapprochement between labor and capital that lasted for years, and reunited the country, all while also finding a replacement for the frontier that led to a whole new generation of opportunities for men like Herbert Hoover to capitalize on.

The other options, the men people on the poll voted for, did some of those things to varying degrees. Whether defending our industrial sector, trying to push taxes down, or trying to find a new frontier for Americans. But none did all of what McKinley accomplished, and none of them did so as successfully as he.

If you found value in this article, please consider liking it using the button below, and upgrading to become a paid subscriber. That subscriber revenue supports the project and aids my attempts to share these important stories, and what they mean for you.

My thoughts on the Twentieth Century:

The British Gentry, the Southern Planter, and the Northern Family Farmer: Agriculture and Sectional Antagonism in North America explains the land price matter in some depth

Particularly, President Cleveland was hostile to tariffs and did his best to push them down dramatically: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_tariffs_in_the_United_States#Reconstruction_era

How McKinley fit into this period discussed here:

On the British system:

This is described reasonably well in The Republic for Which It Stands: The United States during Reconstruction and the Gilded Age, 1865-1896

A great example of this:

Described briefly here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Presidency_of_William_McKinley#Pluralism

Described in somewhat more detail here:

A short description of this: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Presidency_of_William_McKinley#Reconciliation_with_Southern_whites

Described in somewhat more depth here: https://www.jstor.org/stable/4250101

This is described reasonably well in The Republic for Which It Stands: The United States during Reconstruction and the Gilded Age, 1865-1896

Also, it is described simply on page 62 of this Treasury Department report: https://www.goldensextant.com/Resources%20PDF/Gold%20Commission%20Report%20Volume%20I.pdf

Hoover, a young engineer, became internationally recognized for opening hugely productive and profitable mines in Western Australia and China, where he was besieged by the Boxers. He then went on to finance, restructure, and revitalize mines everywhere from Russia to Burma, making a fortune in the process.

Briefly summarized here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herbert_Hoover#Bewick,_Moreing

Described in depth in this fantastic book: Herbert Hoover: A Biography

Discussed here:

One book on that: https://mises.org/library/book/too-much-government-too-much-taxation

A good article on his war on liberty: https://mises.org/mises-wire/deposing-liberty-democracy

Another good article on him; https://mises.org/mises-wire/disastrous-legacy-woodrow-wilson

In any case, even a glance at his domestic program is enough to prove this: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Presidency_of_Woodrow_Wilson#Domestic_policy

Quoted in this brief but good summary: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theodore_Roosevelt#Trust_busting_and_regulation

From the book: T.R.: The Last Romantic

Titan: The Life of John D. Rockefeller, Sr. is a superb book on Rockefeller and Standard Oil

Also, this podcast by Ben Wilson is superb: https://www.takeoverpod.com/episodes/rockefeller

A few articles on that:

You're probably right, but I still got a soft spot for Nixon and splitting China and Russia was a good tactical move and I don't blame him for outsourcing our jobs to China, that was under Clinton.

McKinley got us into the Spanish American War, our introduction to global empire, as we colonized Cuba and the Philippines. Without this entry into Asia, we might have avoided the Pacific theatre of WWII, maybe even the whole thing. Our economic relations with China had a large influence in our strategic diplomacy with Japan. Teddy Roosevelt deserves the credit for developing the Panama Canal, McKinley did very little but help steer it towards Panama over Nicaragua.