Kamala Harris's Unrealized Capital Gains Tax Was Already Tried, And It Destroyed the Greatest Empire the World Has Ever Seen

The Sun Sets When You Tax Phaeton and Helios

Kamala Harris shocked the country and made yet another of her characteristic political mistakes (she failed to win a single delegate in 2020, after all) when she announced that she supported increasing the capital gains tax to 44.7% and creating an unrealized capital gains tax that would tax the unrealized capital gains on assets over $100 million at a 25% rate.1

If there was one thing that could turn women in suburban Atlanta into voters redder than West Virginia, it’s that. So, it’s a terrible political decision unless your goal is losing.

The concept makes no sense: on what day of the year would assets be totaled and taxed? Would there be a refund if they decline in value? Would the government take assets in kind to avoid market-crashing sales, or accept only cash? How would the tech industry survive if founders had to pay immense taxes when their business got its first few rounds of funding and was taxed at an extortionate rate? How would any startup survive, for that matter? So, it’s a terrible economic decision.

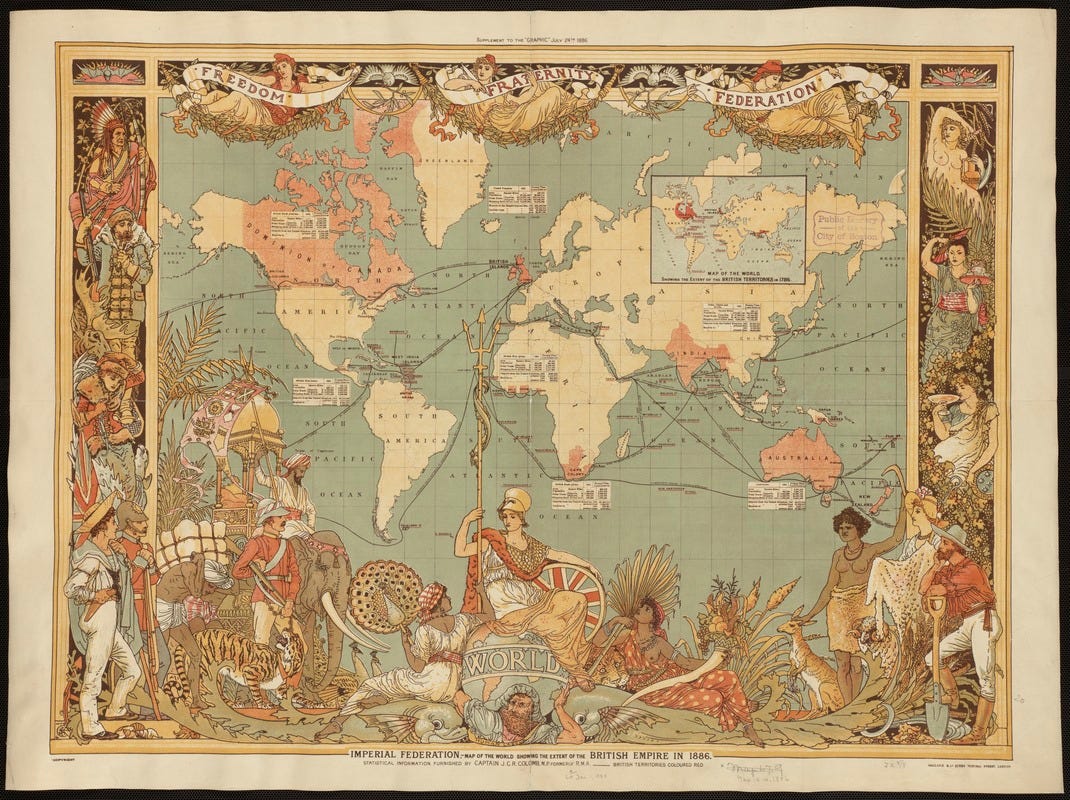

But more than all that, even if one cared not about the political consequences and was economically illiterate (or wanted to crash the economy for equity reasons), there is a crystal clear example of this demented policy being put into practice. It turned the greatest empire the world has ever seen into a pitiful island known now only for its war on free speech and crumbling National Health Service.

That island, of course, is Great Britain. This is the tale of how it turned its advantages to ash with a Kamala-style tax.

Listen to the audio version of this episode here:

Unrealized Capital Gains and Imperial Decline

Of Victorian Vistas and Edwardian Heydays

When England came to the turn of the century and the glorious nineteenth became the soon-to-be disastrous twentieth, it was at the height of its glory. Britannia ruled the waves. Her trade vessels and companies dominated those same oceans and the lands connected to them, and the products they produced at home dominated much of that same world. The shareholders of the companies producing and selling them grew fantastically wealthy, and much of that wealth had been plowed into innovation. That same innovation had, over the course of the prior century, made Her Majesty’s industry and agriculture the envy of the world: England’s mills and mines produced the materials and methods of the industrial century, her agricultural revolution created the immense amounts of foodstuffs necessary for such immense industry, and the landowners and shareholders at the top led the world in class, elegance, and pomp.

There were storm clouds on the horizon, to be sure. Her industry was less at the forefront of innovation than it had been, with much excess wealth flowing to foreign rather than domestic investment and the suspiciously watched Huns building their navy, mines, and industry across the chilly North Sea. Further, the agricultural depression had hurt the landowner class substantially, though not yet beyond the point of repair for all but the most feckless families.2

Generally, however, the Victorian Lion was still roaring mightily. The homefront was prosperous and stable, much unlike the heady days of the French Revolution at the previous turn of the century, the empire was huge and still growing, and the navy that guarded it stood undefeated and still towering over the German and American competition. Over it all stood the still proud and powerful aristocracy, some of it still dating from the days of William and the Normans (for example, the Grosvenor Dukes of Westminster3 and Percy Dukes of Northumberland), and nearly all of it secure in its present position as being composed the leading men of the realm.

Two passages from two of my favorite books, 1913: In Search of the World Before the Great War by Charles Emmerson and The Proud Tower: A Portrait of the World Before the War by Barbara Tuchman are quite relevant, and show the world into which Britain marched before the death duties destroyed it.

The first comes from Tuchman’s Proud Tower:

THE LAST GOVERNMENT in the Western world to possess all the attributes of aristocracy in working condition took office in England in June of 1895. Great Britain was at the zenith of empire when the Conservatives won the General Election of that year, and the Cabinet they formed was her superb and resplendent image. Its members represented the greater landowners of the country who had been accustomed to govern for generations. As its superior citizens they felt they owed a duty to the State to guard its interests and manage its affairs. They governed from duty, heritage and habit—and, as they saw it, from right. The Prime Minister was a Marquess and lineal descendant of the father and son who had been chief ministers to Queen Elizabeth and James I. The Secretary for War was another Marquess who traced his inferior title of Baron back to the year 1181, whose great-grandfather had been Prime Minister under George III and whose grandfather had served in six cabinets under three reigns. The Lord President of the Council was a Duke who owned 186,000 acres in eleven counties, whose ancestors had served in government since the Fourteenth Century, who had himself served thirty-four years in the House of Commons and three times refused to be Prime Minister. The Secretary for India was the son of another Duke whose family seat was received in 1315 by grant from Robert the Bruce and who had four sons serving in Parliament at the same time. The President of the Local Government Board was a pre-eminent country squire who had a Duke for brother-in-law, a Marquess for son-in-law, an ancestor who had been Lord Mayor of London in the reign of Charles II, and who had himself been a Member of Parliament for twenty-seven years. The Lord Chancellor bore a family name brought to England by a Norman follower of William the Conqueror and maintained thereafter over eight centuries without a title. The Lord Lieutenant for Ireland was an Earl, a grand-nephew of the Duke of Wellington and a hereditary trustee of the British Museum. The Cabinet also included a Viscount, three Barons and two Baronets. Of its six commoners, one was a director of the Bank of England, one was a squire whose family had represented the same county in Parliament since the Sixteenth Century, one—who acted as Leader of the House of Commons—was the Prime Minister’s nephew and inheritor of a Scottish fortune of £4,000,000, and one, a notable and disturbing cuckoo in the nest, was a Birmingham manufacturer widely regarded as the most successful man in England.

Similarly, Emmerson, in the opening of 1913, describing Europe generally in much the same terms that could describe the leading nation of Europe at the time, wrote:

To be a European, from this perspective, was to inhabit the highest stage of human development. Past civilisations might have built great cities, invented algebra or discovered gunpowder, but none could compare to the material and technological culture to which Europe had given rise, made manifest in the continent’s unprecedented wealth and power.

…

From Olympus then, level-headed, well-informed, internationally minded Europeans – not cynics, but not dupes either – could still view the world in 1913 with a certain equanimity, their civilisation unmatched, their superiority unchallenged, their peace disturbed only by a few rabble-rousers, martinets and revolutionaries at home, their future guaranteed by the march of progress. Things might come to some kind of scrap at some point, of course. But not today, nor perhaps tomorrow. When over, equilibrium would be re-established and calm restored. Olympus would remain inviolate, the dangers to it not negligible, but not unmanageable either. As it was, the sun still rose each morning over Europe from behind the Urals and still set each evening into the wide Atlantic. The stars above remained fixed in the firmament.

Such was the world at the turn of the century, particularly in Great Britain. The government was quite limited, and most of what it did amounted to expanding, protecting, or administering the empire, all of which was excellent for British industry. The officers in the army, the colonial administrators and governors, the members of Parliament, and the local landowners and justices of the peace, were almost all peers or relatives of peers.

Critically, that small coterie of men at the top had the resources, foresight, and tradition to do what was beneficial to the state. On one hand, they served in the aforementioned roles and positions largely without a salary of note; even when a salary was introduced to roles formerly without it, such as MP, it was never enough to cover the expenses of a gentleman, but rather a token of the state’s gratitude.4 On the other, they were the investors who built Britain into what it was. They were the ones who invested in and provided the land for the railroads. They rented or, in the case of the leading men like the Fitzwilliams, ran the mines that powered Her Majesty’s ships and lit the fires of the great steel mills. They built the infrastructure to ship out such goods, such as the Marquesses of Bute, who built the great port at Cardiff. And, to build and retain their wealth as the economy transitioned from agricultural to industrial, they provided the debt and equity necessary for the great firms of England to be created and thrive; others were involved, of course, but it was largely peers and gentlemen who provided the capital.

In short, as the Lion roared and Britannia stood guard, it was the great peers and lesser gentlemen who stood behind them. Everyone else, from “new men” in business to poor agricultural laborers, was involved. However, it was those who danced in the London Season and chased foxes across the countryside who captained the forces, steered the ship of state, and funded the businesses making Britain great while growing the food to feed the workers of those businesses.

The Lion is Maimed

Within half a century, all of that was gone. The great peer-run mines of the Fitzwilliams were seized by the state, as were all the others. The railroads and steel mills, which a century before had signaled the arrival of the industrial era, were seized as well, becoming nationally run shadows of their former glory.5 The great country houses for which Great Britain, particularly southern England and the moors of Scotland, was famous had been shuttered in many cases and reduced in the scale and glory of the hospitality they could provide in the others.6 Many hardworking Englishmen couldn’t find work, as the factories were shuttering alongside the magnificent country houses they formerly funded, and great estates on which their ancestors had worked had since been broken up in estate sale after estate sale, becoming anything from minor farms not in need of work to land lying fallow for want of will and reason to work it.

The navy had been bested by the Japanese, of all people, in embarrassing incidents, the no longer aristocratic army had performed barely better than the Italians, and only the knights of the air had any relation in spirit to the roaring Lion of the Halcyon Era that was now well past. Britannia’s former shield, the once-proud and formerly wave-ruling British Navy, had been largely chopped up and sold for scrap in the wake of the war, something over which Nelson and Jellicoe likely rolled in their graves.

Even food was no longer what it once was. While Englishmen of the “earlies,” or early Victorian period, were renowned for their beef-eating and resulting health, and the feasts of country houses were renowned for their taste and scale throughout the period leading up to the Great War, food remained rationed and of poor, processed quality in the years after World War II. Once renowned for their hearty fare and magnificent hospitality, the English of the socialist-run post-war era ate canned beans on nutritionless toast as country houses sat vacant and rotted.

Now, England couldn’t even be described as a shadow of its former self. Instead of being ruled by stodgy but proud Victorians or hard-drinking but intensely hierarchical men of the Regency, it’s ruled by bureaucrats who let Muslim invaders rape children for reasons of cultural sensitivity.7 Its navy can’t even keep Suez open, much less rule the world’s waves, and its army would be hard-pressed to retake Ireland, much less rule with a firm fist an empire on which the sun never sat. Meanwhile, it has no domestic industry of note other than Rolls Royce, which makes cars and jet engines, and a few small sartorial and firearms firms like Cordings, Burberry, Purdey, and Holland & Holland. Saville Row and Barclays are great, but tailoring firms and banks owned by foreigners8 are hardly the sort of thing on which national prosperity rests. Gone, to put it mildly, are the days of industry to rule the waves with the Limeys. On the agricultural and country side of things, Clarkson’s Farm is a representative example: with a few exceptions, the great estates are gone, and what agriculture can now function is largely dependent on government grants and regulation-following rather than world-leading innovation.9

Taxes Caused It

There are a host of reasons for England’s decline. Free trade hurt the agricultural sector and great estates that relied on it.10 Both world wars were mistakes for England that cost it men and money it couldn’t afford. Electing Labor in the post-war era, the ‘60s, and the present has meant immense amounts of bureaucracy. But, worst of all, and probably most problematically, have been taxes, namely the death duties.

Now, we can turn to the real subject of this essay: taxes, particularly the death duty.

Important to remember, when reading about the heyday of the English, is that it was all achieved by nearly non-existent taxes. The amount a man paid before the socialism that closely followed the turn of the century was probably around 8% or so, if that. Further, death duties, or death tax, originally introduced to combat Napoleon, had died out until the late 1880s, when they were reintroduced at a low, but still mildly alarming, 1.5% for the great estates. AJP Taylor, describing the era, wrote:

Until August 1914 a sensible, law-abiding Englishman could pass through life and hardly notice the existence of the state, beyond the post office and the policeman. He could live where he liked and as he liked. He had no official number or identity card. He could travel abroad or leave his country for ever without a passport or any sort of official permission. He could exchange his money for any other currency without restriction or limit. He could buy goods from any country in the world on the same terms as he bought goods at home. For that matter, a foreigner could spend his life in this country without permit and without informing the police. Unlike the countries of the European continent, the state did not require its citizens to perform military service. An Englishman could enlist, if he chose, in the regular army, the navy, or the territorials. He could also ignore, if he chose, the demands of national defence. Substantial householders were occasionally called on for jury service. Otherwise, only those helped the state who wished to do so. The Englishman paid taxes on a modest scale: nearly £200 million in 1913-14, or rather less than 8 per cent. of the national income. … broadly speaking, the state acted only to help those who could not help themselves. It left the adult citizen alone.

Things started changing in 1894, when the death duty system was revamped. At that point, the death duty became a much more alarming 8%. Because of how the tax worked, planning around the problem became much more necessary.

As a reminder from our article on free trade and English agriculture, that sector was in serious trouble in the 1890s due to low prices. As a result, acres of farmland were much harder to sell. The nouveau rich lost interest in buying estates that now made no economic sense, and too many old families had to sell. So, though land nominally retained much of its former value, it was hard to sell at a fair price, and selling enough to cover the cost of death duties on a great estate, which would often include other highly valuable things that the family would not want to sell, such as the country house or the magnificent paintings of past family members. However, the state wouldn’t accept payment in kind, so acres couldn’t just be handed over to the state to pay the tax, and even if they could, that would still break up and destroy the great estates). Instead, land had to be sold in an awful market to pay the death duties, meaning that selling more of it than was nominally necessary was required to pay off the extortionate state. In short, death was treated as a realization event though nothing had been sold, and so the estate’s long-held assets had to be sacrificed for the benefit of a rapacious state though no wealth had been realized by their sale.

While that was bad enough, it was bearable, and most families had assets more liquid than land, such as stocks and bonds, so they could find a way to survive the situation.

It then got far worse, thanks largely to supposed conservative icon Winston Churchill. He, by 1910 a Liberal largely for reasons of electability, partnered with Liberal politician Lloyd George to ram the People’s Budget through Parliament in the 1909-10 period.11 It raised death duties to the sickening amount of 15%, and, more importantly, sparked the crisis of The Diehards in the House of Lords.12 The problem, to put a long past and somewhat esoteric issue succinctly, was that the Lords didn’t have any interest in passing the People’s Budget, and refused to do so. Commons struck back with the Parliament Bill, which removed the power of the Lords to veto a financial bill at all and limited their veto on other issues to holding up the bill at issue for a mere two years. The Lords wanted to veto the Parliament Bill, but risked being diluted by peers created to pass it if they refused to pass it. In the end, enough went along with the 1911 Parliament Bill to pass it.13 At that point, the decidedly middle-class and lower-class-dominated House of Commons could pass whatever it wanted.

Commons did so and turned death duties up to the following extortionate levels:14

in 1910, 15% on taxable amounts over £1,000,000

in 1914, 20% on taxable amounts over £1,000,000

in 1919, 40% on taxable amounts over £2,000,000

in 1930, 50% on taxable amounts over £2,000,000

in 1939, 60% on taxable amounts over £2,000,000

in 1940, 65% on taxable amounts over £2,000,000

in 1946, 75% on taxable amounts over £2,000,000

in 1949, 80% on taxable amounts over £1,000,000

in 1969, 85% on amounts in excess of £750,000

Nowadays, both the UK and America have 40% death taxes for great estates.

Two key matters there are important.

One is that the rates were obviously extortionate. If a family was so unfortunate to be struck by a death in the state-enforced bloodbaths of World War I or II, or any other death or deaths during the period, it faced seeing up to 85% of its assets gone. As the families owned great country houses with immense value, libraries with thousands of valuable books, vast painting collections, and their agricultural and real estate empires, that meant seeing nearly all of their land go. Some could, until the capital transfer tax was passed, avoid the death duties by passing the assets as gifts (no tax on gifts if the giver didn’t die within 7 years of the gift) or by putting the assets in trusts.15 But, sadly, many were walloped by the socialist taxes for which they had Churchill and the socialists he empowered to thank.

The other issue is that the estate amount never went up. In fact, it went down over time. That came despite massive inflation over the half-century due to the spending required for World War I and II and the spending allotted for welfare programs. So, even as the government devalued the currency, it taxed more and more assets thanks to that inflation.

The death duties devasted English society, particularly the aspects of it that made England great and powerful.

The gentry and aristocracy now had to work and sell much of their land, so they could no longer afford to serve for low pay abroad, furthering imperial glory. Instead, the empire was given up, and the gentlemen were replaced by bureaucrats.16

The English economy was devastated by socialist policies generally, becoming a hollow shell of its former self in the 1940s and early 50s under Attlee and never really recovering. It didn’t help that the men who could have invested in rebuilding the country after the war were instead broke, with all their assets going to the government instead, to be spent on some welfare program or another.

Finally, English cultural greatness is now gone. In the world before the Great War, the world of still limited death duties, England was the country life capital of the world. Its country house life, from stately manor homes to fox hunts and bird shoots, was imitated the world round, and huge amounts of wealth from America (the Morgan family, for example), South Africa (the Rand lords), and further abroad had poured into the English countryside; all who could afford it wanted a country estate in England. Death duties made them avoid it: what was the point of buying an estate that would just be taxed into oblivion by an evil and rapacious government? Better to just avoid it.

Thus, England became what it now is rather than what it once was: a land of socialist tyranny and poverty rather than freedom and prosperity. America faces much the same future with Kamala and her unrealized capital gains tax.

How Kamala’s Plan is Similar

The sad fact is that Kamala’s plan would result in a tax that would be even worse than the death duties for two reasons.

As mentioned earlier, the death duties treated death as a realization event despite no land having been sold and inflation decreasing the value of those assets while the government kept taxing them. Kamala’s initiative would be yet more destructive in that it would treat the end of every single year as a realization event. So, instead of being able to avoid the tax by sticking assets in a dynasty trust, as the Grosvenors do,17 or gifting them ahead of death, the tax has to be paid no matter what. Whether the assets are held, sold, or gifted, the government would steal 25% or more of the gain on them. In being entirely unavoidable, with inflation raging in the background and driving down the worth of those assets, Kamala’s tax would be even more destructive and impoverishing. Adding to the destructiveness of Kamala’s plan compared even to the death duties is that England didn’t have a capital gains tax for much of the heightened death duties period, so assets could be sold to pay it without incurring another tax. Not so under Kamala’s plan. Under it, there will be a realized capital gains tax of over 44%, so that tax will be incurred when selling assets to pay the unrealized capital gains tax.

The second issue is that Kamala’s plan, or any unrealized capital gain or wealth tax, would utterly destroy the American spirit. If England was the land of established fortunes, America is the land of building them. The only reason anyone would take the risk of building a company, working hard at it, and taking risks to build it into something great is that they might build a great fortune by doing so. Americans have done that in various forms since they arrived on these shores, whether the planters of the early South, the early textile barons of New England, the Rockefellers and Carnegies of the Gilded Age, or the tech company masters of the universe today. And while the great have done so on a great scale, America has also always been the land of small business and small-scale entrepreneurial activity. Taxing wealth continually after it has been earned would utterly destroy that. Who would take the risk necessary to earn a fortune if a quarter of the unrealized gain on that fortune is stolen by the government every year and a huge chunk must be sold to pay the unrealized gain taxes? Perhaps a few who build things solely for the greater good, but all who do so because of their entrepreneurial, American spirit would stop doing so. As a result, the greatest economy and engine of innovation the world has ever seen would, like the British one before it, be destroyed by what amounts to a wealth tax punishing the successful for merely existing.

Perhaps that is Kamala’s goal. She is a socialist, after all, so it’s not hard to imagine she wants to destroy America. Regardless of her goal, however, the fact remains that an unrealized capital gains tax of the sort she wants has, in a less destructive form, been tried before. The result is that it destroyed the greatest empire the world had ever seen, the British Empire, and destroyed the once-great, prosperous, and innovative English economy and beautiful English society in the process. That is what we’re up against.

![[AUDIO] Kamala Harris's Unrealized Capital Gains Tax Has Already Been Tried; It Destroyed the Greatest Empire the World Has Ever Seen](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!hI30!,w_140,h_140,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-video.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fvideo_upload%2Fpost%2F148043749%2F32c23dcb-1442-43b7-9145-3692304ed51c%2Ftranscoded-1724427627.png)

It's been said that bad ideas are immortal, and the parallels between Britain's death duties and the Harris "unrealized gains tax" proposal certainly seems consistent with that. Your analysis put me in mind of an observation from a great British mind, the late Cyril Northcote Parkinson:

-- Wasting the labour of the people “under the pretence of caring for them” is exactly what our governments do. Freedom is founded on ownership of property.... It cannot exist where the rulers own everything, nor even when they concede some limited right of tenure. But the modern belief is that spendable income is a concession of the State. The taxation which is intended to promote equality, the taxation which exceeds the real public need, and above all the tax which is so graduated as to prevent the accumulation of capital, is inconsistent with freedom. Against a State which owns everything, the individual has neither the means of defence nor anything to defend....

There are many human achievements, including some of the finest, which need more than a single lifetime for completion. The individual can compose a symphony or paint a canvas, build up a business or restore order in a city. He cannot build a cathedral or grow an avenue of oak trees. Still less can he gain the stature essential to statesmanship in a highly developed and complex society. There is a need for continuity of effort, spread over several generations, and for just such a continuity as governments lack. Given the party system more especially, under the democratic form of rule, policy is continually modified or reversed. A family can be biologically stable in a way that a modern legislature is not. It is to families, therefore, that we look for such stability as society may need. But how can the family function if subject to crippling taxes during every lifetime and partial confiscation with every death? How can one generation provide the springboard for the next? Without such a springboard, all must start alike, and none can excel; and where none can excel nothing excellent will result. --

May God bless and keep you.

Running out of other people's money is a distinct possibility.