Country House Nationalism Against the Global Favela

The Two Options

Welcome back, and thanks for reading! Today’s article is something different, more of an op-ed style article than a research article or book review. I figured it’d be fun to try something different, and try to set my thoughts to paper in a different way than normal, while also getting to a solution to the problem rather than just critiquing. Please let me know what you think, and if you like this form of article! And, as always, please tap the heart to “like” this article if you get something out of it so Substack knows to promote it. Listen to the audio version here:

The whims of fashionable behavior have dictated that the wealthy, especially the nouveaux riches who are in the public eye—actors and famous managerial capitalists of the modern sort—must not pass on the wealth they have spent their lives building to their children. Instead, they are to spend what they can in whatever frivolous ways seem pleasurable, and then hand what remains to charity so that it can line bureaucratic pockets in the name of the public good. “Die with nothing,”1 some call it. “The Giving Pledge” is another common name.

The personification of the Global Favela—that physical manifestation of the dank, fetid pit of equality—and the antithesis of the Western spirit is its best definition. We must reject it, and instead choose the sort of civilization represented by the stately country home: one premised on natural hierarchy, tradition, and order.

What, after all, was the common form of Occidental governance before the Great War wiped it away? Monarchy supported by aristocracy.2 The idea that a realm is to be stewarded, and passed from one generation to the next by a great dynasty that preserves, cultivates, and furthers the mission and spirit of a people over the ages. Tradition had a home in the hallowed halls of the magnificent palaces of those bedecked with crowns and coronets, beauty and refinement were not just cultivated but championed, and the people had stewards to whom they could turn in times of need.

This social compact sometimes broke down, as in 1789 and 1848, but it was remarkable for its general stability. Even the American Revolution meant only that it would be the Virginia gentry and their sort who would rule as enlightened gentlemen, rather than the Tory squires who had pushed them into conflict.3 What is shocking about 1914 is not that the old order died in its wake,4 but that an essentially medieval society marched off to a modern war, with levies of commoners led to battle by an aristocratic order composed of those who, like Hugh Grosvenor,5 could trace their lineages back to the age of chivalry, or even before it.

Indeed, other than a few hiccups, nearly all of which were easily suppressed, the old order of stewardship, hierarchy, and tradition lasted well into modernity and outlasted its contemporary competitors.

The Paris Commune was crushed, the revolutions of ‘48 did much more to bring about abolitionism in America than liberalism in Prussia, and nobody today even knows of the Chartists. Liberalism survived like kudzu, of course, but who today thinks it will last for a thousand years like the hierarchy represented by the Grosvenors, Princes of Liechtenstein, or Princes of Thurn und Taxis?6 Liberalism’s post-war variation already seems a bit geriatric and sclerotic, and it has ruled for less time than the Stuarts. Meanwhile, Liechtenstein is still stewarded by its royals and is one of the wealthiest lands on Earth. The reigning prince, Hans Adam II, even wrote a book on good governance, The State in the Third Millennium.

Even in those lands that drifted away from the monarchic ideal, embracing instead republican and democratic thought—Britain was damned during the 19th century for its democratic tendencies, and Albion’s seed flowered into a decidedly democratic fruit—the tendency toward embracing stewardship and tradition rather than base expropriation ruled.

Traditional society was, in Burke’s words, “a partnership not only between those who are living, but between those who are living, those who are dead, and those who are to be born”.7 That was seen not just as an ideal, but as a duty, mindset, and mode of behavior that had to be met for one to be a true gentleman and member of the ruling elite.

Life on the country estates of Virginia8 and Britain best characterized this (though the following is about Britain, as the examples are the best-documented, all of it applies to the general Virginia gentry as well, and thus America).

Those who had money or obtained money, from Bess of Hardwick9 to William Armstrong, sunk it into the great estates and manor houses that ruled over them, doing so “from an ambition to leave our names behind us, rooted into the soil to which the national life is attached,” in the words of J.A. Froude. It was from that soil-rooted ambition that the great names of England’s history sprang, and in the soil they remained rooted. The North Knew No Prince But a Percy as the Percys fought the border reivers for generations while forever anchoring their ambitions on Alnwick.10

John Churchill returned from leading armies back “in the days when dukes were dukes,” as his descendant Sir Winston put it, to anchor his name on the baroque splendor of Blenheim. Cliveden passed from Grosvenor to Astor and became the seat of the pro-Empire Cliveden set as they tried to stop Sir Winston from again plunging the nation into war.11

In each case, the estate supported the house—a thousand acres per bedroom, by the old rule of thumb—and the house supported the dynasty. Through it, they grew their roots and set about imprinting their ideals on the face of the nation. The country houses and estates in which they lived were the tools with which they attempted to steer the nation in the name of tradition and noblesse oblige.

To hold on to those drafty, capital-absorbing piles of brick and marble was no mean feat. The roofs are seemingly always in need of repair, the servants’ bill was always eye-watering, and everyone who could called upon the family’s hospitality at the slightest justification. But they were maintained nonetheless, and supported as they grew more expensive not by money-grubbing in the City, but by multi-generational estate improvement.

The vast rents were rarely frittered away by feckless heirs of today’s “trust fund kid” type, even if the estates were sometimes stewarded by six-bottle men and bon vivants, but instead reinvested in estate improvement. Fortunes were spent many times over on field drainage, improved agricultural stock, replanting forests, new fences, new mines, and even new ports.12

Led by the great agricultural improver Coke of Norfolk, the agriculturalists supported their position while feeding the Industrial Revolution with the Agricultural Revolution they developed; without them, Britain could not have been the preeminent industrial empire it became. The Earls Fitzwilliam set the standard in mine safety, being among the few coal owners not despised by the common folk who worked in the mines.13 The Marquesses of Bute built the port at Cardiff with their own resources,14 and it was the Grosvenors who imprinted upon Mayfair and Belgravia the beauty that remains to this day, while also developing the empire by doing everything from settling cotton farms in Rhodesia to building an industrial island in Canada.

Because the horizons of those who ruled were infinite, improvement projects that would lead to future wealth and power in the community were invested in, even if capital-draining in the short term. The principle of stewardship meant those multi-generational projects, from field drainage to the beauty of Mayfair, could arise and be completed, as their costs could be sustainably borne over decades rather than requiring quick repayment.

Yet further, because the landed elite had its dignity to maintain rather than just pocketbooks to replenish, it generally did its improving and development in accord with the principles of noblesse oblige rather than the profit-maximizing attitude for which the mill owners became infamous. A gentleman does not flay his sheep, and was expected to act in such manner. Largely, they did, even as the 19th century drew to a close.15

With stewardship and improvement in mind, the vast majority of the class went from success to success with each generation rather than from shirtsleeves to shirtsleeves. Meanwhile, the wealth built and retained by such practices served as the basis for the service for which the aristocracy was famous.

Even before Old Etonians suffered a ~20% death rate while leading their men through the bloody fields of Flanders, it was they who served as Justices of the Peace in the counties, served in Parliament without pay after shouldering immense election expenses, officered the armies that won the colonies, and then administered those colonies. At the beginning of the Second Anglo-Boer War, Lord Roberts had three young dukes—Marlborough, Westminster, and Norfolk—serving under him; a bit blue-blooded of an officer corps, perhaps, but at least they served. The same couldn’t be said of the units that helicoptered into Vietnam or rolled into Iraq, for America’s silver spoon sorts stayed far away from service by then.

Leadership, service, and stewardship were the characteristic virtues of the old elite and were inexorably intertwined with their form of wealth. Even in a rotten borough, a lord could not win elections if his tenants despised him, would not have the wealth to serve in any capacity if he mismanaged his lands, and would no longer be a man of note if frivolity or exigency led to him losing his lands. Their world was intertwined, much more so than any asset and noble behavior today.16

It is not for nothing that Mr. Darcy of Pride and Prejudice is described by his servant as “the best landlord, and the best master…that ever lived; not like the wild young men nowadays, who think of nothing but themselves. There is not one of his tenants or servants but will give him a good name.” That was the ideal. The hierarchy that supported such men only continued to exist because of their dignity, virtue, and stewardship, and only lasted so long as they generally represented it as a class.17

Such an attitude was exported to those lands they settled and influenced as well. For example, the Astana-dwelling White Rajahs of Sarawak were vastly more concerned with development, public services, and justice than the Malays, Sultans of Brunei, and the headhunters they defeated. In like manner, the farming estate-based great men of Rhodesia were better for all than the native tyrants they displaced.

Similarly, Virginia’s gentry was imbued with the same ideals of noblesse oblige, tradition, and hierarchy as the cavaliers who gave the Old Dominion its distinctive flavor.18 From that came their aristocratic focus on duty, dynasty, and service, which was supported by their country house-ruled estates, like Monticello, Montpelier, and Stratford Hall.

Then, the catastrophe of the 20th century brought the old world of country homes and service to a crashing end. After nearly a century of social peace, the People’s Budget renewed the social conflict with a deadly vigor. Its tax rates were intolerable, the class war element of it was infuriating, and the clear goal was to separate the aristocracy from its land, the basis of its virtues and power, in the cynical name of the common good.19 The Parliament Bill went even further in separating the stewards from stewardship of their country.

What followed were years of social strife interspersed with wars that rended the social fabric yet further. Death duties crept inexorably up, going from the 15% seen as so intolerable when proposed before the war to the peak of 85% seen in the Harold Wilson years. Income tax rose similarly, reaching a peak of 99.25% under Churchill’s wartime government; investment income taxes reached a peak of 98% in the 1970s.

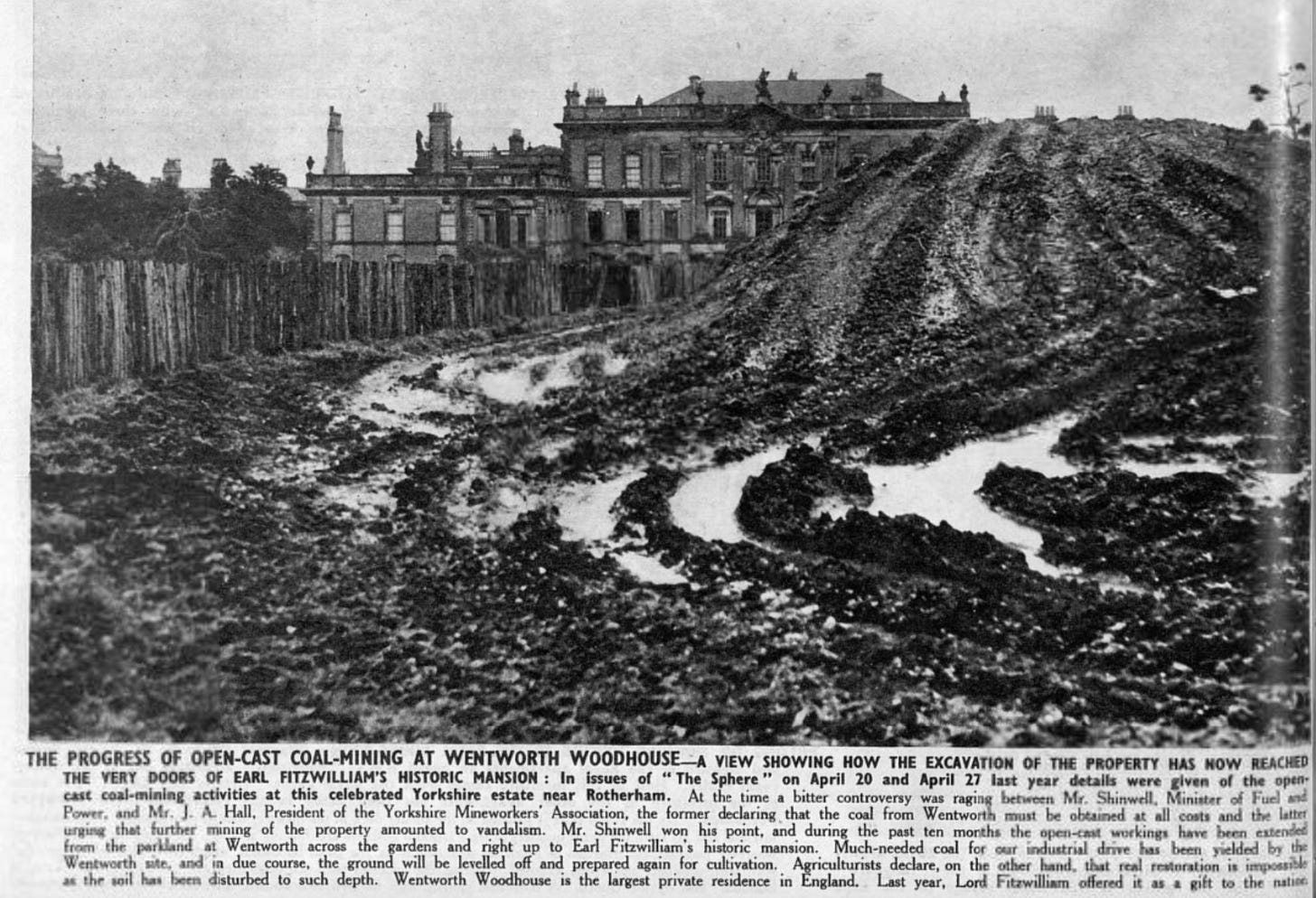

The great houses of even those who could pay the endless, house-destroying taxes20 and fees were appropriated21 by the government during and after the Second World War, with families already being taxed into penury being kicked out of their ancestral homes so that the state might use them for one bureaucratic purpose or another, often leaving them in a decrepit22 state if it handed them back at all.23 The coal fields of the Fitzwilliams were expropriated by Attlee’s Labour regime over the objections of the miners themselves, and the spiteful open-cast mining that followed allegedly left the foundation of Wentworth Woodhouse indelibly damaged and the beautiful park destroyed forever.24

In the name of the people, what had been Merry Old England was destroyed. What replaced it was a tidal wave of taxation and regulation, paired first with Council Houses and the NHS, and then a flood tide of mass migration and its unavoidable consequences.

Now, the Starmer regime has considered levying another 20% tax on farms25 so that enough revenue can be raised to pay for the annual amount26 Britain spends on supporting foreign farmers. That a bit of foreign aid could be foregone so that cherished rural tradition could survive doesn’t appear to have been a consideration: the whole point is to tax the country house and its estate into oblivion on behalf of the Global Favela and its rice supply.

America and the Continent saw expropriation, 90+% death and income taxes, and regulatory assaults on private property in the name of “the people” as well. What would have been seen as inconceivably monstrous in 1910 had become an inescapable fact of life by 1970, as the Occident fell under the merciless grip of a stultifying bureaucratic tyranny that outlawed success, dynasty, and concern for the future while pointing to the supposed common good as its justification.27

The natural result of such onerous and spiteful taxation has been to destroy the old order and the form of life that supported it. Where once localities were governed by those who had lived there for time immemorial and loved the place and inhabitants, they are now ruled by bureaucrats and busybodies of the sort made infamous by Clarkson’s Farm.28

Where once families who had been tied to the soil for centuries owned and improved it,29 now solar parks dominate productive farmland that lies dormant and fallow. Where once great families lived and partied in country houses that served as the seat of political and dynastic ambitions that built the country, now the National Trust stuffs modern art abominations into dead homes confiscated by taxation while squeezing visitors for ever-higher fees.30 The fox hunts and Palladian houses for which England was famous have been outlawed and destroyed by decades of miserable and spiteful bureaucracy, all while the “Grooming Gangs” blight Britain, seemingly without a single impediment.

In America, we see lands brought under the yoke of civilization by settlers who fought deadly bands of Indians for the privilege of squeezing a bit of corn and tobacco from the soil paved over, so that land that might once have supported a small community and church can be filled with grey apartment complexes that support strip malls full of jabbering foreigners. Fast food boxes hand out obesogenic grub atop land that once served as cattle pasture, mountain streams are littered with refuse left by imported workers from the “developing world.” No one can say or do a thing, for it is a vast and uncaring corporation or bureaucracy that controls the land on which aesthetic and moral abuses occur, rather than a man of note who cares for the soil and human beings atop it.

Meanwhile, the improvement and development that could make our world better is eschewed for much the same reason. Regenerative agriculture often suffers from a lack of capital despite being a bright spot in a dismal sector, for we have few modern Coke of Norfolk31 types willing to pour their lives and fortunes into bettering the food of the people. Public life suffers from a lack of beautiful buildings, clean spaces, and civilized amenities.

Vagrants, meanwhile, have the run of places controlled by bureaucrats or fund managers who care little for the quality of life of residents, and only for what taxes and rents can be squeezed from them. Utilitarianism, apathy, and squalor have overtaken us. As the country house and the civilization it built have died, the Global Favela, a stinking pit of equality, has overtaken us.

The war on the old manner of life is clearly to blame. Every era has its vices as well as its virtues, and what used to exist was no exception. But its virtues were at least of a generally pro-social sort.

Does anyone today believe our oligarchs would use their wealth to die in the trenches at a 20% rate, as the Old Etonians did, or might a shocking proportion have heel spurs and asthma that regrettably prevent such a sacrifice? Would members of Congress “serve” in it if not given wages, healthcare, and pensions? Are residents of richer neighborhoods known more for trying and succeeding to escape jury duty, or for doing what they can to follow in the footsteps of their justice of the peace ancestors, a tradition that was as alive in the Tidewater as in Wessex back when the old world existed? No, our elite is composed of lesser sons of greater sires, if it can trace its sires at all, and so fails to do any of those pro-social things.

Such is what the death taxes accomplished, to the extent they could. The unrelenting decades of asset confiscation little different from that seen in Zimbabwe, other than that fewer Kalashnikovs and machetes were used, have wrought a great change in society. They have separated wealth from duty and ownership from responsibility. The point of an asset is seen not as serving as the foundation of a dynasty that will carry one’s ideals and tradition into future ages as part of the great compact described by Burke, with all the duties and responsibilities it entails, but rather as a mere means by which as high a return as possible can be squeezed.

Where things are still made and new wealth built, the knives come out quickly; California moving to expropriate the wealth of tech founders,32 with the El Segundo-based33 members of that crowd being just as targeted despite being some of the last real builders in America, is representative of the attitude, though it afflicts everywhere. Death and wealth taxes have done what they were meant to do, which is destroy the aristocracy and gentry as a class while also destroying its virtues, pushing all that now-latent power into the hands of bureaucrats.

Yet worse, the attitude represented by The Giving Pledge and like initiatives aims to make such cultural and social destruction voluntary. There are still some men who use their wealth to do as they ought—Elon Musk pouring his wealth into saving free speech online being one of the bigger examples—and the mind virus of giving it all away aims to destroy them.

The upper-middle class is told not to think of itself as potential gentry,34 with children who could serve and build rather than being as yet another banker or consultant, but rather as only temporarily wealthy and needing all generations to remain forever on the treadmill as each generation gives it all away to the frivolous charities and Marxism-pushing NGOs.

Were it up to those behind the push to give all wealth away, Elon Musk would not be embarking on a necessarily multi-generational project to terraform and settle Mars, but rather living hedonistically while planning to give it all away so that nothing great might ever be done. All this in the name of “the people,” of course; “the people” of the Global Favela prefer welfare to rockets, the NHS to the world-spanning achievements of empire, and the idol of indolence to the achievements of vitality.

Such is the attitude of the Global Favela. Whereas the great titans of the Anglo-Normans spent their time atop Olympus building greatness, we now are smothered by a grey and suffocating, yeast-like tyranny focused forever and always on mere existence and biomass.

The Space Age had to be cancelled to fund the Great Society’s welfare schemes. The Atomic Age must be forever postponed to assuage the worries of the ignorant about the difficulty of boiling water. The great empires had to be shed so that ever more expansive and generous welfare programs could be funded for one generation, and then an Esau-like policy of selling the civilizational birthright for a bit more pension program funding by importing foreign hordes engaged in to make the programs last one generation longer.

The cost of giving in to indolence, of embracing equality-driven stupefaction and torpor, of giving in to the Global Favela, is everything Western man used to hold dear. The benefit is that it frees one of having to think of living up to the duties of his ancestors: when the purpose of life is merely existing while looking like everyone else in a drab, grey sweatsuit out of which one’s belly pokes as the pension check arrives in the mail, none dare think of building for future generations with the same surname.

That is the mindset that “die with nothing” and “The Giving Pledge” aim to inculcate through propaganda, and is the same sort of message that was sent by the ruinous death taxes of the 20th century.

Civilization thrives only when old men plant trees in the shade of which they will never sit. But old men will not plant such trees when they are told doing so is “selfish” and immoral, and that in any case the forest will be taxed into oblivion before it reaches their heirs so that some bureaucrat has a pile of wood to set purposelessly alight. So, instead of towering forests full of the trees of civilization, we get decay arising out of the thought that all projects must end with the stopping of a heart’s beat, and indeed probably shouldn’t have been embarked upon in the first place.

Thus, the Global Favela creeps into our lives in the same manner as it destroyed the gems of the colonial world. And make no mistake, the fate of the colonial world is the fate those who have destroyed the country house to subsidize the Global Favela would inflict upon us.

The fate of the Belgian Congo is a good guide, as it shows what was intended.

The Belgians, through much hard work over much of a century, turned the Congo from the Heart of Darkness into a jewel of Empire. Where once there was only trackless jungle inhabited by cannibalistic warlords, slavers from Zanzibar, and the downtrodden masses over whom they ruled, the Belgians brought the light of civilization and cleared out the fetid rot that had accumulated from time immemorial. With them came modern railways, asphalt roads, hospitals, schools, and what Professor Bruce Gilley called “the only period of good governance that this benighted region has ever known.”

Such is what could be achieved by a vital and self-confident civilization applying the force of its will for generation after generation in a compact between those who were and those who were to be, and the rich resources of Katanga flowed forth as a reward. Then came the decay; the bright light of vitality was snuffed out, and as Albion and America destroyed themselves with generational compact-destroying taxation, the colonial world destroyed itself in the name of the same rotten goal: equality.

And so all that was accomplished was never to return, and even in Mike Hoare’s day, the dense jungle was creeping back over the Belgian-built roads.35 Now, as shown in Empire of Dust, nothing remains. Those with no thought of planting trees for future generations allowed it all to fall to ruin, often actively and intentionally destroying what had been left behind, whether out of spite at the colonizers or apathy at the benefits of civilization. Now darkness rules again, and the Belgian accomplishment is smeared and slandered by those who wish to justify its destruction.

The same can happen here. The same is happening here. It is being intentionally inflicted upon us. The Global Favela, the physical manifestation of equality, has been chosen over the country house, the physical manifestation of hierarchy and tradition. The result is that we’re all heading toward the fate of the Belgian Congo.

We must rage against the dying of our civilizational light, and hold on to what of our civilization can be salvaged so that we can build anew. To do so, we must recover the old world mindset, the mindset that maintained the great lords in their houses for a millennium.

The present is not all there is. It matters very little, in fact. Beauty does not flourish in a high-time preference world like ours, one that builds strip malls instead of cathedrals. Achievement does not occur when shackled by taxation that hands over its rewards to those crying for endless aid to be shoveled at vast expense into their gaping maws. Mars will not be terraformed if we fund the Great Society and aid for the former colonies instead.

Civilization is a partnership between those who are living, those who are dead, and those who are to be born. It is a compact best represented by the great dynasties and their houses, a choice to always build and strive to create the future while honoring the past, rather than wallowing in the predatory pleasure of decadence or the languor of equality.

Escaping the bounds of the firmament and becoming multiplanetary, rebuilding the prosperous and competent future of which our ancestors dreamed, recreating a world in which future generations can find joy and fulfillment rather than be crushed by the heavy yoke of dismal equality, these are the goals towards which we must strive. They are by necessity a multi-generational compact, a partnership between all the hallowed branches of the family tree.

For that tree to grow into a beautiful old-growth forest, we must reject the presentist thinking and the dynasty-destroying tax policies and philanthropic pressures that come with it and instead embrace the creed of the country house, the symbol of natural hierarchy, of order, of tradition—of civilization itself.

Featured image credit: Wentworth Woodhouse by Kevin Waterhouse, CC BY-SA 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

If you found value in this article, please consider liking it using the button below, and upgrading to become a paid subscriber. That subscriber revenue supports the project and aids my attempts to share these important stories, such as the recent one on Civil War, and what they mean for you.

Also, please check out my new YouTube channel, where I’m telling the stories of great adventurers and great families, starting with the Brooke Dynasty, the White Rajahs of Sarawak:

Johann Kurtz wrote a good article on this:

A good popular history style book on this is: The Fall of the Dynasties: The Collapse of the Old Order: 1905-1922

The Last King of America: The Misunderstood Reign of George III gets into some of this, and is a fun read

The Decline and Fall of the British Aristocracy by Cannadine gets into this, from a British perspective

Bendor: The Golden Duke of Westminster by Leslie Field tells the story of his wartime service well

Aristocrats by Robert Lacy tells their stories well

This connection between Burke and landed society was made in JV Beckett’s The Aristocracy in England, one of my favorite books on the subject

The First Gentlemen of Virginia notes this well

Her story is told in the delightful The Serpent and the Stag

Kings in the North by Rose is the delightful telling of their story

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cliveden_set

Their story is told in Tragedy & Hope by Caroll Quigley

In addition to the aforementioned books, the best general study on this is The English Landed Estate in the 19th Century: Its Administration by Professor David Spring

Cardiff and the Marquesses of Bute is a good book on them, and noblesse oblige

English Landed Society in the Nineteenth Century by FML Thompson is the best book on this, in addition to the aforementioned ones. Cannadine notes it as well, as does Spring

Amongst many other sources, this is noted well in Coke of Norfolk and His Friends, and English Landed Society in the Eighteenth Century

The Decline and Fall of the British Aristocracy by Cannadine tells of this, as does Noble Ambitions by Tinniswood

Clifford Dowdey notes this well in The Great Plantation

The Diehards is the book to read on this

Noble Ambitions by Tinniswood tells this story in heart-wrenching detail

This is covered well in Mellon by Cannadine, a book I wrote about here:

https://www.theamericantribune.news/i/186643350/13-mellon-an-american-life-by-david-cannadine

Coke of Norfolk (1754-1842): A Biography is the best single-volume biography of him

Johann Kurtz wrote a good book in part on this called Leaving a Legacy

This is described well by Mike Hoare in his fabulous Congo Mercenary

Great article. I like your creation of Global Favela.

Humanity will never live on Mars or the Moon long-term. It will all end in failure. Nor will we ever be multi-planetary. But not because of what you outlined in your excellent writing above, but because the Bible shows it to be so.

We would be better off if Musk focused his fortune on helping make what you write about come true, sans the space colonizing stuff.

Oh, and thank you for all the book references.

I consistently admire your work. This piece inspires a lot of thoughtful chewing on the concept of duty. I fear that the concept is entirely alien to contemporary culture, no one recognizes it, no one does it. How did we get here? Is it just an inevitable consequence of human nature, have we been manipulated by combinations of evil men, is it the work of Satan? How does this all turn out? While I struggle to remain hopeful, I’m pretty sure there will be blood.