We're Going from First World to Third

Dark Days

Welcome back, and thanks for reading! Today’s article is one that’s been on the top of my mind since I reviewed Lee Kuan Yew’s From Third World to First for the recent article on it and the Cultural Revolution. While not the focus of the book, it is one of the more incisive points in there, and so one I wanted to cover in a short article. I hope you find it as interesting and valuable a lesson as I do; it’s one that stuck with me over the years. And, as always, please tap the heart to “like” this article if you get something out of it, as that is how Substack knows to promote it!

What is it that defines Third Worldism,1 that caustic and rotten attitude that characterizes so many of our world’s blighted and hellish lands? Why did former jewels of the colonial world like Rhodesia and the Belgian Congo, once shimmering beauties in the Dark Continent, fade to mere stinking mudheaps as they rejected what the Europeans had wrought in their lands? Why does the Ganges remain putrid and septic?2 How did Guatemala City go from being the pleasant and “clean” city of the late colonial era to the hellish zone of squalor and crime it now is?3

What, in short, is it that defines the perpetual state of enervation, indolence, and brutality for which the Third World has been known since the Europeans were forced to depart?

Listen to the audio version of this article here:

There is the matter of not thinking of the day after tomorrow, the state of being shown in Empire of Dust,4 and indicated by there being no word for “maintenance” in most African languages. That, of course, causes problems.

So does the spiteful and resentful outlook of the post-colonial world, the idea that equality ought be achieved not by bettering the unfortunate but by tearing down what greatness used to exist and replacing it with the equality of the dungheap.

But all of that is well known: it is no revelation to say that the Congolese have failed to steward the railways that the Belgians left them.5

There’s another element as well, one that is often forgotten: a sense of apathy toward the shared public space. A sense that everything which exists exists to be exploited, abused, or neglected rather than cherished, refined, and stewarded.6

In such a world, a street is not a clear and clean area on which one can get from A to B, whether as a pedestrian or driver. It is an open spot that can be filled with rickety and unsanitary stalls, a place where refuse can be dumped, or even an area where one can stretch his legs, shoot up some drugs, and pass out.

Squalor and filth. Misery and decay. Congestion and overcrowding. Such are the terms that can be used to define how the Third World views public areas and, as a result, into what those commons have turned with the departure of the Europeans. What could be pleasant avenues or clean parks are instead mere patches of turf to be taken advantage of for short-term personal pleasure and gain, whether that be selling slop from an unregulated cart or pouring out a mound of fly-ridden, foul-smelling garbage on which a vagrant might decide to sleep.

That attitude towards public spaces isn’t just representative of the Third World, nor is it a mere symptom of the total lack of social trust present in those hellish lands. Rather, it is what helps create them. The filthy wretchedness and pervading grime help create the attitude of merciless apathy towards suffering and self-destructive selfishness for which these societies are known.

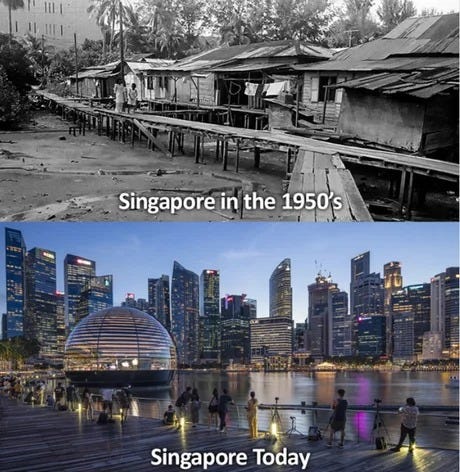

The Singapore Story

Such is what Lee Kuan Yew came to understand and set out to correct in Singapore’s early days. He understood that filthy habits should not be treated with the romanticism due a rustic world, but harshly repressed so as to create a refined and excellent culture in which one could build for the ages rather than speculate and self-deal with the understanding it might all be buried under a mountain of garbage, literal or figurative.

And there was much to criticize with the state of the city in its early days of independence. When LKY came to power, as he recounts in From Third World to First, Singapore was a muddy little city characterized by tropical heat-induced torpor and the medieval-like slovenliness of its denizens. Pigs roamed in the streets and munched on the garbage poured into them by inattentive inhabitants. Drunkards and workingmen alike were known to urinate in the street. Filth that killed the fish and fouled the water was poured into the fetid Kallang River. Most of the city-state’s buildings were squat, filthy structures notable only for being rude relics of the timeless Orient, however much it might lose its luster when viewed in closer detail.

All of that had to be corrected if Singapore was to be taken from Third World to First: what company would invest in any industrial facilities of note in what amounted to a filthy swamp with a port attached, and what country would take the seemingly titular ruler of such a place seriously?

So, set out to fix it LKY did. He banned public urination and chased the hogs off the streets. The muddy roads were paved, and the rudimentary shacks and stalls that used to line them banished to select quarters. New, modern buildings with lethargy-defeating air conditioning units were erected all over the island. These became office buildings and housing units, teaching the population first how to care for the goods attendant to modernity—beds and couches, A/C units and radios—and then how to iterate and build atop that foundation to achieve greatness.

It took long, hard, painful work. Rustic old residents had to be taught not to keep pigs and chickens in their new apartment homes. Bans on unsanitary chewing gum had to be ruthlessly enforced.7 Vandalism was punished by caning. Cleaning the Kallang was a massively expensive undertaking.

But, gradually, the changes began to tell. Fish returned to the Kallang, and the toxicity levels remained low enough that they could be eaten. The streets remained clean, and turned into modern thoroughfares connecting an increasingly highly skilled and wealthy populace with the high-tech factories, modern shipyards, and towering office buildings in which they worked. Singapore went from being a somewhat romantic but quite downscale relic of the decayed colonial past to a modern city-state that embraced the best of modernity while keeping the new forms of disorder and decay at bay. It became a financial hub, a stable outpost of the old West in the Orient, and massively wealthy.

All of that was only possible because LKY had the spine of steel necessary to drag the inhabitants of Singapore from Third World to First, particularly as regarded personal habits that impinged on shared public spaces.

Garbage and the pigs that ate it would no longer be dumped in the streets. Gum was banished so it wouldn’t blight the city’s surfaces. The rivers were cleaned of ordure and kept free of it moving forward. No longer, in short, were a gloomy sense of grime-ridden decay nor the habits that created it to be tolerated. Corruption went from being common to bans on it being strictly enforced.

Virtue was enforced, and care for the dignity of public spaces was demanded. As a result, Singapore was turned into a shining jewel of the Orient, a city-state known for its technological advances, prosperity, and clean desirability. That is how it went from Third World to First.

The Occident’s Decline into Slovenly Decay

Sadly, America—and indeed much of the dying West generally—seems to be reverting to the Third World pattern. To be going from First World to Third.

This is obvious in the declining habits exhibited by most of the population, the lack of any sense of public decorum or refinement, the signs of higher civilization that were built up over generations.

Take matters of dress: in our days of civilizational vitality, our time on the ascent, there were clear codes regarding looking civilized in public, for how you presented yourself to the world was a sign of inner order and respect for those around you. Hence why “gentlemen,” the state of being that obsessed our Founders, took the time and expense necessary to wear formal dress as they went about their daily lives.

Similarly, that sense of public decorum and respect for others is why even the working poor of the Victorian and Edwardian eras, or the Gilded Age for us, owned and wore suits. Even the laborers wore collared shirts on the job, and even the poor had a suit to wear when out in public, to show they cared about how they presented themselves in public and were tirelessly improving themselves.

The beauty of life in the not-so-distant past. From: X

Just look at pictures from the time: workingmen worked in waistcoats, soldiers (officers and enlisted alike) fought in formal dress, and public spaces were kept beautiful. Even as late as World War II, our officers wore ties as part of the service uniform.

All of that served a purpose, and it wasn’t vanity. As covered by Bushman in The Refinement of America, the point of dedicating the time and resources necessary for refinement—an attitude exhibited even on the rough American frontier by yeomen farmers—was to be part of the vital, humming civilization that was on the ascent. To show and reflect self-improvement and familial advancement. To grasp onto and develop inchoate traditions, and once they were fully formed, develop them into the splendor for which they were known.

The purpose of life in the First World, over this period, was not just a drab existence or dreary utilitarianism. It was advancement, creation, and glory, and the habits of the people maintained and furthered that. Following in the footsteps of the upper orders, those most clearly on the ascent as prosperity firmly took hold, everyone in society joined in and showed—through their dress, manners, and interests—that they too were on the ascent.

So, when we had the resources to go from painting one’s small house on the frontier being a major expense to constructing the great centers of civilization that still stand—Grand Central Terminal and the Empire State Building, for example—there was no thought but to do it well and beautifully. The foundation of wanting to continue advancing the line of civilization, of building for forever in a way that lifted the spirit with created beauty—and to show that same respect and care in one’s dress, manners, and life—already existed and could be built upon.

Yes, all was not perfect. Injustice forever and always exists, and many towns in the coal centers and forested wastes were anything but beautiful or glorious. Still, the conditions for a flowering of civilization were generally present, and that flower did blossom. Something great was obtained, and it was reflected in the attitudes of those there for the ascendant stage of civilization, particularly in their care for the public space.

They dressed well in it, behaved well in it, and beautified it to the extent they could, raising impressive and beautiful buildings that have well stood the test of time.

Modern Decline

Now, not so much. We are reverting from First World to Third, and it’s visible in our constructed environment.

Just take a look around, the next time you’re out.

The buildings are not pretty, particularly if new constructions: they are, rather, drab and unpleasant structures, theoretically meant to be utilitarian (though in reality far more expensive to maintain8 than beautiful buildings are to build and keep), but in reality just depressing.

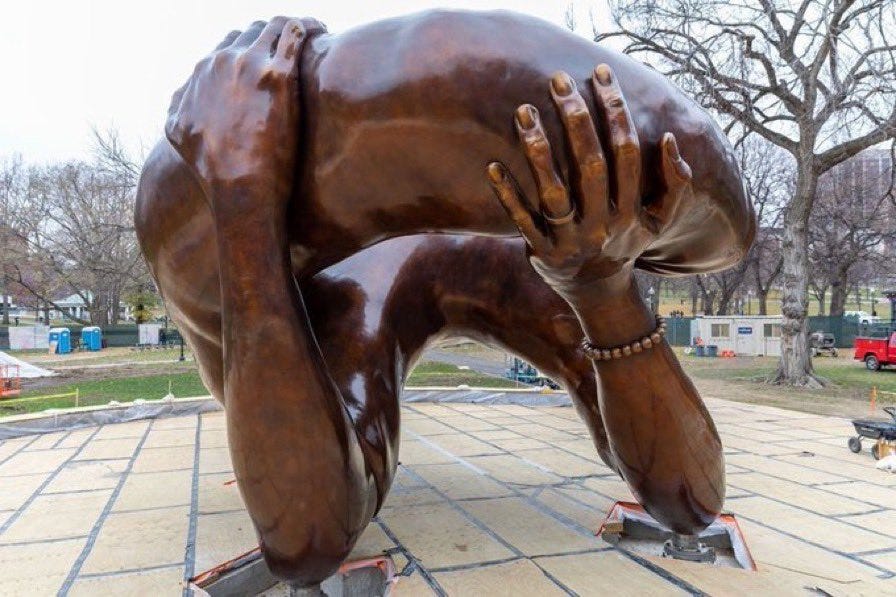

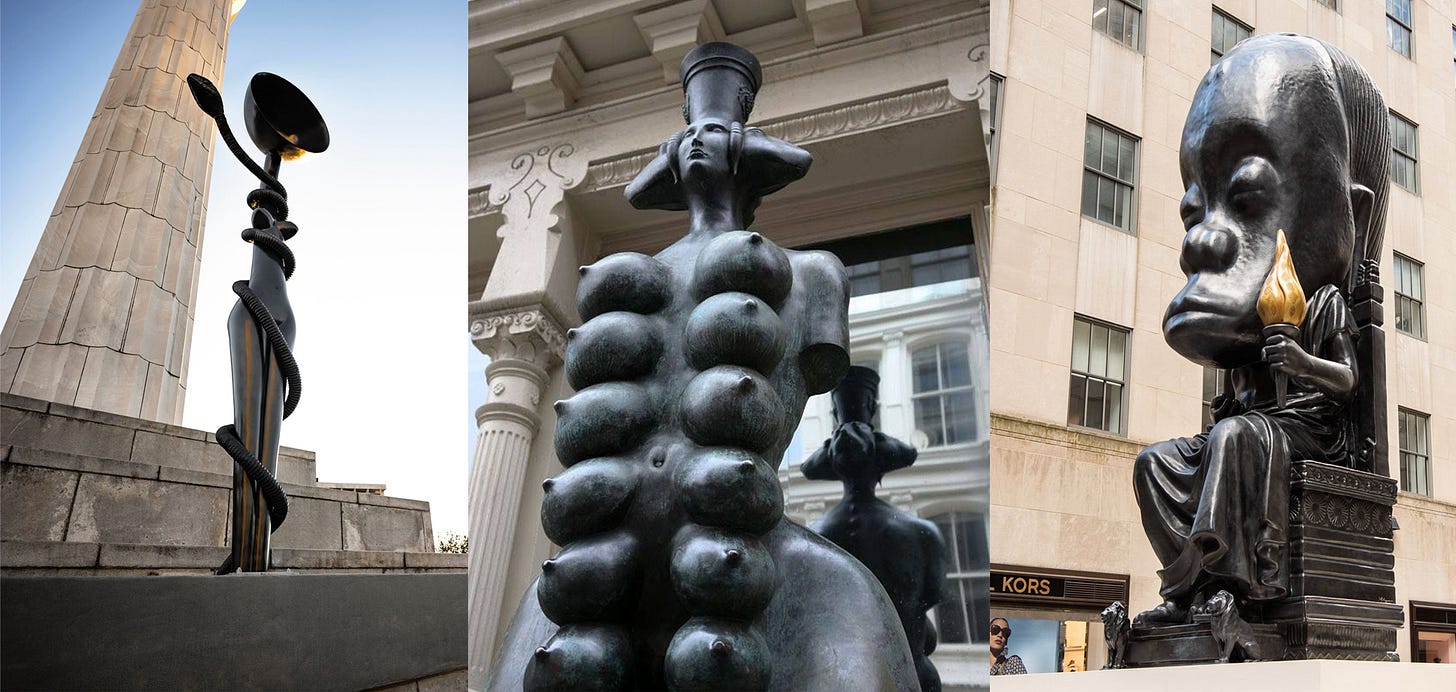

What statues are raised are almost uniformly horrifying and dispiriting. They do not uplift the spirit, tell of a glorious past, or cherish beloved heroes. They instead shock and disgust, push depression and dreariness, as is their point. The same is true of modern art generally, as it rejects refinement or beauty in a quest to appall and create a sense of revulsion.

Then there is the matter of slovenliness and decay. Even the wealthy—particularly the tech oligarchs—are too lazy and careless to dress well and set an uplifting example others might follow, as the wealthy of yesteryear did.

They instead give in to their own indolence and bedeck themselves in outfits less formal than even the laborers of a few decades ago. They embrace slovenliness and the decay it represents rather than striving to present an example of something higher and glorious that others might emulate.

Naturally, being ruled by such lesser sons of greater sires is having ill effects, and the inner disorder and insouciance represented by our totalizing drift toward informality is playing out in the realm of our cities.

Now, in cities that were once dignified centers of commerce and culture, Third Worldism rules. The streets swarm with vagrants, many of whom feel no shame as they defecate and shoot up in public. Drug dens fill city blocks, and parks are strewn with homeless encampments and streetside peddlers, most of them here illegally and selling counterfeit goods. Grime encrusts the pavement, long lines of rats stream through the haphazard piles of garbage, and little to nothing gets done without an ungreased palm.

That is what Third Worldification looks like. Yes, America is far wealthier than Equatorial Guinea and the Congo. But, in our urban zones, do our streets look more like something one might find in the Kinshasa of the present or the Singapore LKY built? Have we stewarded what God and our ancestors blessed us with, and built upon it to glorify them and Him? Or have we instead let it fall to ruin, letting the South Africanization of our world take grip because we lack the spiritedness to reject it?

The sad fact is that we have let it slip through our fingers. Like the heir of an heir returning to the shirtsleeves of his grandfather, we’ve reclined upon the idol of indolence and let the collected capital of countless generations—our civilizational inheritance—fall to ruin.

Whereas our ancestors strived for mightier and more glorious accomplishments, ever more beautiful public spaces, and dignity with which they could grace them…we have lazily embraced slovenliness and ugly decline that sets no example other than how to degenerate as a people. And so we have gone from First World to Third, seeing social trust and noble deeds evaporate before our very eyes as the deterioration of our public spaces explains why it is happening.

There is little to do about that other than to rage against the dying of the light and be what you wish to see in the world. As was understood even back in classical times, one is not truly virtuous unless one is not just flourishing oneself but encouraging the flourishing of one’s people. Such is why the gentlemen of days past did all they could to set an example for those with the inner fortitude to attempt a course of self-improvement. They dressed to show respect for those around them, built beautifully for the ages, encouraged learning, and beautified public spaces.

We ought do the same. We ought reject squalor and sloveniness, decline and despair. We ought build, cultivate, and encourage in what ways we are able. Yes, that is often a headache and rarely appreciated…the boiling crab seeks to prevent others from escaping the pot, not to escape himself. But it is all we can do, and what we should do. Third Worldism must be rejected; embracing the spirit and forms of our ancestors, as best adapted for the present, is how we can do so.

This does work. New York City experienced a Renaissance under Rudy Giuliani because his broken windows policing meant disorder and the characteristic signs of squalor that attend it weren’t tolerated. The forces of entropy were—for a time—checked, and the city’s residents reminded that there was something more than filth and decay.

Be the Broken Windows theory in your life. Dress well. Behave well. Live excellently. That is the First World mindset, and must be embraced just as disorder, entropy, and slovenly filth are rejected.

Featured image credit: Rhododendrites, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

If you found value in this article, please consider liking it using the button below, and upgrading to become a paid subscriber. That subscriber revenue supports the project and aids my attempts to share these important stories, such as the recent one on Civil War, and what they mean for you.

A great thread on characteristics of the Third World by one of X’s greatest posters: https://x.com/kunley_drukpa/status/1888912740267262042

This is a point Curtis Yarvin makes in his Open Letter:

If you read travel narratives of what is now the Third World from before World War II (I’ve just been enjoying Erna Fergusson’s Guatemala, for example), you simply don’t see anything like the misery, squalor and barbarism that is everywhere today. (Fergusson describes Guatemala City as “clean.” I kid you not.) What you do see is social and political structures, whether native or colonial, that are clearly not American in origin, and that are unacceptable not only by modern American standards but even by 1930s American standards.

I wrote about this here, if you are interested: https://x.com/Will_Tanner_1/status/1843671114918334860

Please let me know if you’d like for this to be a full article

Rory and I talked about this here:

This is discussed here: https://x.com/kunley_drukpa/status/1839706275694674421

The expense of these horrors: https://x.com/DmitriyMolla/status/1978075137837818163

![[Audio] Going from First World to Third](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!_15y!,w_140,h_140,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-video.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fvideo_upload%2Fpost%2F176158184%2Fb4580d1e-acf8-4cbd-96a4-d87cff775d2d%2Ftranscoded-1760461262.png)

Simply outstanding article. I'm an older fella now, so I hate to sound like the geezer saying "When I was a kid...", but, I have never forgotten when I was a small boy visiting my grandparents- must be 50 years ago or so now- and we were going out. I was leaving the house in a clean t-shirt. "What are you wearing!" gasped my grandmother. "Absolutely not!" and in I went to find a shirt with a collar. T-shirts were for wearing under other clothes. To this day, if I'm not wearing something with a collar, I don't feel like I've finished dressing. Respect for ones self and others starts at home. I miss my grandma.

IQ is a HUGE factor. As is the nuclear family model; depart from either at your peril.