Abandoning Project Independence Gave Us Global Zimbabwe Instead of Martian Rhodesia

Energy Is Life

Welcome back, and thanks for reading! Today’s article is a guest article from my friend A. J. Rees, who has deep experience in energy markets and was intrigued by the article on how we have spent more on aid to decolonized Africa than it would have cost to settle Mars, and so chose to look into the matter from the perspective of energy, the lifeblood of modernity. It’s a fascinating article from a man who has long been involved in the energy field, and one from which I think you’ll learn lots. I certainly did. Mr. Rees’s work on energy matters can be found on X @EnergyTrendsJPN or on Substack at Energy Trends JPN. Finally, as always, please tap the heart to “like” this article if you get something out of it, as that is how Substack knows to promote it! Paid subscribers can listen to the audio version here:

The twelve months between December 1972 and the end of 1973 rank alongside 1914, 1918, 1929, 1939, 1941, and 1945 in terms of their importance to the twentieth century. December 1972 saw the final Apollo mission, the last time human beings set foot on the Moon. October 1973 saw the beginning of the Oil Shock, which marked the end of a quarter-century of unchallenged American economic dominance.

From that peak, the Steel Belt became the Rust Belt. Detroit entered its decades-long decline, and the slow hollowing-out of America’s manufacturing heartlands began, leaving in its wake depression, misery, and poverty.

It did not have to be this way.

Just as disastrous was the fact that, as The American Tribune has argued, Western civilisation might already have settled Mars, but instead chose “Global Zimbabwe”. The problem was not just one of aid and wasted resources, however. It was also one of energy, and the West’s refusal to become energy independent. It all boils down to energy, in fact.

It is for that reason that I want to examine another missing pillar, Project Independence, and how it would have been essential for making humanity a truly multi-planetary species while preserving American industrial supremacy into the twenty-first century.

Project Independence and Energy Supremacy

Civilisation runs on energy. It always has, and it always will. Whether it is the energy stored in muscle, in falling water, in coal, or in boiling steam turning a turbine, the principle is the same. Energy is what makes the world go round.

This is why Richard Nixon’s response to the 1973 oil embargo was to launch Project Independence1 on 7 October 1973, with the explicit goal of making the United States energy self-sufficient by 1980 through a massive expansion of nuclear power and electrification.2

“The lessons of the Apollo project and of the earlier Manhattan Project are the same lessons that are taught by the whole of American history,” Nixon told the nation.3 “Whenever the American people are faced with a clear goal and they are challenged to meet it, we can do extraordinary things.”

The idea was straightforward. By electrifying industry and households with nuclear power, the United States would slash its long-term dependence on oil, relegating petroleum largely to transport and petrochemicals, and shielding its economy from price shocks like the Arab Oil Embargo then underway.4

Sadly, it was not to be.5 A combination of rising costs, regulatory fragmentation, political fatigue, and public fear slowed the programme to a crawl. Far fewer nuclear power stations were built than had been planned, and soon America stopped building them entirely.

But what if the project had continued and overcome these hurdles? Counterfactuals are usually slippery, but in this case, we have a real-world example: France.

The French Connection

For all their sterling qualities—being almost, but not quite, as good as the British in naval warfare, their superb women, and their passable wine—the French have also demonstrated how nuclear electrification can and should be done.

Through a sustained, standardised nuclear build-out, France has become one of the most heavily nuclear-powered nations on Earth.6 The result of this buildout has given France an extraordinary energy price stability. While oil and gas prices lurch between booms and busts,7 nuclear plants quietly delivered gigawatts at steady output, year after year, from both domestic uranium8 and friendly suppliers abroad.

Markets and investors love stability.9 A 1GW nuclear reactor steadily produces 1GW today, tomorrow, and next year. This is partly why lunches with French energy executives tend to be so long: once the plant is running, there is very little for them to do.

This could have been America’s reality.

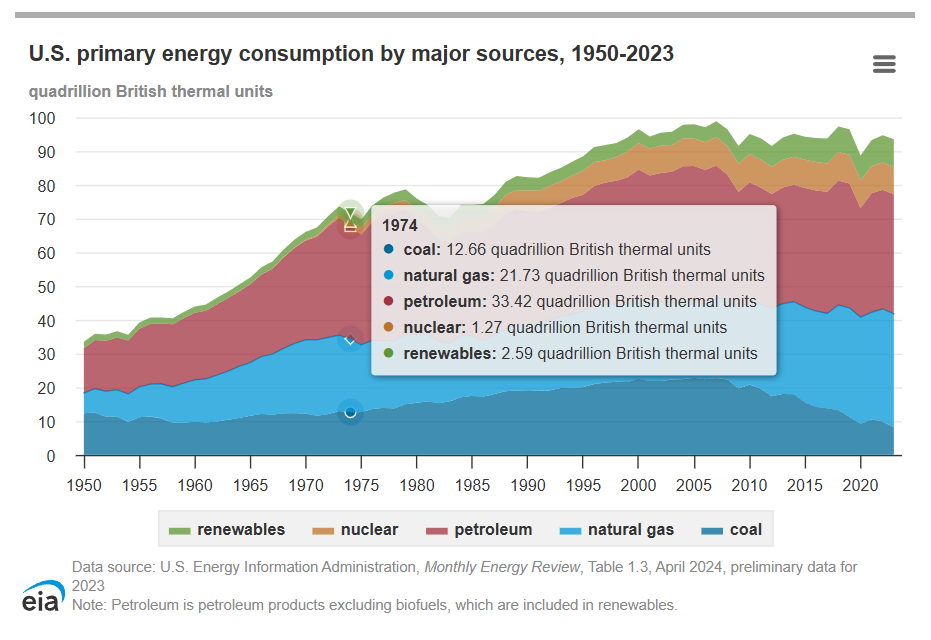

In 1973, the United States consumed roughly 33 quadrillion BTU of oil and over 21 quadrillion BTU of natural gas.

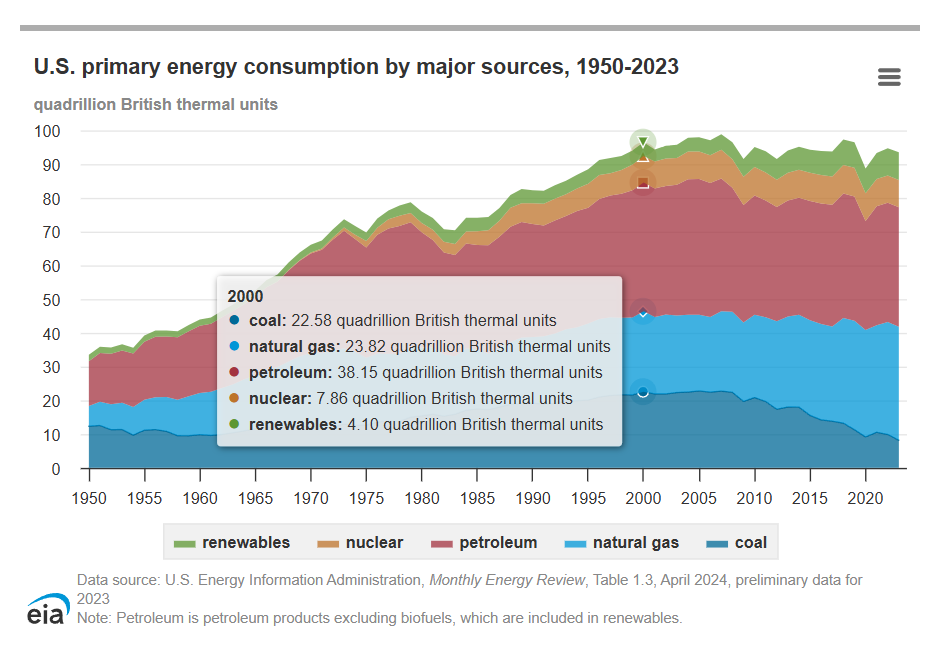

By 2000, these figures had risen to about 38 and 24 quadrillion BTU, respectively.

Had Nixon’s nuclear electrification programme succeeded, a large share of this demand could have been eliminated. Any domestic shortfall could have been met by supplies from Canada and Mexico, effectively ending America’s strategic dependence on the Middle East.

Removing 10–15% of global oil demand would have meant permanently lower prices.10 That, in turn, would mean the diesel to fuel the trucks and trains would have been both cheaper and generally insulated from price shocks, sheltering American industry from the havoc of the oil shock days.

Further, cheap and stable electricity would have transformed the economics of steel mills, aluminium smelters, cement works, and chemical plants. Much as America’s natural gas dominance now gives its chemical companies an edge over most foreign competitors,11 all of industry could have had that edge, starting in the 70s, had Project Independence gone forward as planned.

The cascading effects of that energy dominance advantage would have been both significant and hugely beneficial. The case for offshoring entire industries would have been far weaker. The Rust Belt might have remained the beating industrial heart of the USA, and more importantly, trillions of dollars in welfare funding could have been avoided in the ensuing decades, and the massive amount of outright funding and productivity lost to the costs of despair—primarily crime and drugs—could have been avoided as well. Had it maintained its energy dominance through Project Independence, America could have remained the preeminent industrial power it had been known as until the energy shock decimated its domestic manufacturing sector.

That continued dominance might have come at the cost of the Japanese12 or Korean13 Economic Miracles, with nothing to say of China, but I think the steel worker in Ohio or the cement worker in Michigan wouldn’t have been too put out knowing that someone in Japan wasn’t taking his job and was instead going to work on the family rice farm.

So why didn’t it happen?

Too Many Chefs, Too Many Recipes

Nuclear power is not complicated in principle. First, you make the heat. Then you boil the water, which creates the steam. The steam turns a turbine, which in turn generates electricity. You then sell that electricity and get the money. Some even say you get the women! It is the same thermodynamic principle that has powered civilisation since the Georgians and Victorians used coal and Thomas Newcomen’s innovations to unshackle man from the limits of muscle, water, and wind power by which he had forever been constrained.

While the basics weren’t overly difficult, the real problems for Project Independence’s nuclear rollout at this scale lay primarily in design and regulation. In the 1970s, every reactor vendor and every utility built bespoke plants. There was no single, standardised national design. Each new project instead became a one-off engineering experiment, vulnerable to cost overruns, delays, and regulatory changes mid-construction.

As a result, the costs of producing nuclear power capacity exploded,14 rising from roughly $160 per kilowatt to well over $1,300 in a few short years. Added to Project Independence’s woes was that when the oil crisis eased, the political urgency that had once been behind nuclear energy evaporated. Election cycles ticked on, and the public was more worried about the costs of the project than the independence that could be granted by it.

The Three Mile Island incident in 1979 then caused expansion of America’s nuclear fleet, which was already slow, to grind to a screeching halt, with safety commissions launched and a growing pile of new regulations imposed. By 1990, the United States had built 192 reactors. An impressive figure, but far short of what would have been required to fully electrify its industrial base.

The 1970s Were Not Your Grandfather’s America

A point must be made about the people of America at this time. When Nixon delivered his speech in 1973, calling for a Manhattan Project level of commitment, the average fighting-age man who served in World War II was in his 50s or early 60s. These men were born into the Great Depression, shaped by the greatest conflict the world has ever known, and returned to build a land of plenty. Yes, they would have been the planners and executives, but their children, born during and after the post-war era, would have been the ones doing the shovel work.

The Manhattan Project and the Apollo Program were driven by resolution: we could not let the Nazis be the first to build the bomb, nor the Soviets to gain a superior foothold in space. Building a fleet of hundreds of nuclear reactors to save the average citizen a few hundred dollars on his fuel bills was not, especially when oil prices fell, such an unavoidable imperative.

The post-war generation, splintered by Vietnam and used to the finer things in life, whatever the opportunity cost of focusing on such short-term luxuries over long-term investment, were fine with trundling along well enough. They’ve continued with that mindset to today, and the nuclear fleet buildout was never completed, along with countless other issues going unsolved.

Energy, Industry, and the Road Not Taken

Falling short of delivering hundreds of reactors, combined with the lack of energy from the American populace at large for great feats of daring, was not only a tragedy in terms of economics, but also for the greater civilisational ramifications.

The American Tribune notes that the trillions spent managing industrial decline and welfare could, in another timeline, have funded space settlement. This was not a fantasy. In the 1960s, Stanley Kubrick genuinely feared that 2001: A Space Odyssey would look quaint and obsolete by the time its title year arrived,15 which is hard to imagine in 2026.

Abundant nuclear power would have meant cheaper steel, cheaper aluminium, cheaper cement, cheaper transport, and a permanently larger, much more productive economy. The tax base would have grown. Research budgets would have grown. Launch systems, orbital construction, and closed-loop life support would have matured decades earlier.

The firms that built reactors in the 1960s and 1970s, had they been allowed to scale, would have standardised designs, driven down costs, and learned how to deploy compact reactors rapidly. The small modular reactor now being rediscovered for AI data centres in the 2020s could have been commonplace in the 1990s or 2000s, not for computing power, but for industry. Why buy power from a utility when you can have your own SMR16 or three?

It is only now, with the AI datacenter boom, that we’re seeing significant new developments in nuclear power of the sort that could and should have occurred decades ago. For example, Meta is signing deals to supply its datacenters with 6.6GW of power through power purchasing and development of small reactors.17

As China covers vast swathes of the country,18 including valuable farmland, in solar panels,19 America could be the world leader in developing small, modular nuclear systems that work at all levels, from small towns to the needs of large-scale industrial cities, that can be thrown up in short order.

We are now heading toward such a future again. We could have been there thirty or forty years earlier.

Why This Matters for Space

Any off-world civilisation requires power. Solar works especially well due to no atmospheric interruption, but weakens with distance from the Sun. Wind on Mars is possible, but the planet’s thin air means huge structures for nominal output. Hydrogen fuel cells powered the Apollo missions and are useful medium-term solutions, but are limited at scale, as they need a secondary power source to create the hydrogen.

Nuclear is compact, reliable, and ideally suited to closed, hostile environments.20 Every serious plan for lunar bases, Martian cities, or asteroid mining ultimately rests on fission—and, one day, fusion.

A sustained American nuclear programme would have produced tens of thousands of engineers, operators, and technicians skilled in building and maintaining exactly the sort of systems that off-world settlements require. Energy infrastructure is the skeleton of civilisation; without it, you have flags, footprints, and abandoned rovers. With it, you have colonies, settlements, and the opportunity—in a few hundred years—for we British to turn to our American brethren and console them after losing the New World Colonies on Mars as we once lost them.

The Added Bonus of Being Multiplanetary

Being multiplanetary provides humanity with a pressure release valve on a civilisational scale not seen since the Age of Exploration.21

Ever since those first satellite photos of the Earth, we have been faced with the existential crisis that there are no new lands to find and explore. Our frontiers on this world were not only closed22 but fixed, and our energies turned elsewhere. Space travel, the final frontier, allows us a near-endless opportunity for expansion.

All those illegal immigrants looking for a life in the USA? Get your arse to Mars. Think America, England, or France is evil, and the worst thing that ever happened? Go and build your Communist Utopia in Utopia Planitia.

To the naysayers who say, but why spend money when there are hungry people here, I say this: When Europeans crossed the Atlantic, they did not wait until every child in France had shoes and every slum in London was cleared. They went, built, and in doing so created the wealth that later transformed the societies they had left behind.

The same logic applies to space. The favela should be left behind as we escape the bounds of the firmament, much as America’s colonists left the slums of the Old World behind when travelling to the New.

Space exploration and our limited forays into the Earth’s orbit have shown us the huge possibilities for new technologies,23 materials,24 medicines,25 and so on. Things of which we cannot even dream could be created in the heavens.

Had we focused on greatness and independence through continuing Apollo and completing Project Independence, all those billions and trillions of dollars in aid and welfare could have instead been allocated to building, job creation, and the creation of a multiplanetary civilisation that would have given us technologies,26 materials,27 and solutions we are still only theorising.

Jordan Peterson’s assertion that you should first clean your room is right and proper. You need to be in a good place to do great things. He said nothing about cleaning your town, let alone the endless and eternal favela.

The Price We Have Paid Is One We are Only Beginning to Realise

It is estimated that the burning of the Library of Alexandria set human civilization back about 400-500 years. Add to this the ground lost out on when Nixon’s nuclear push fell flat, and a few other setbacks—such as the wasted time and resources of decolonization, not to mention the egalitarian brain rot behind that catastrophe—and our civilisation could easily be 500 years ahead. The poorest American today has healthcare and luxuries that could only be afforded by the wealthiest sliver of the upper class a mere century ago.

Project that forward five hundred years. The technologies available to even the least prosperous could be godlike by our standards.

Nixon offered America and the world the chance to raise ourselves to energy abundance that would have shored up the American economy and changed its geopolitical position.

To all of our loss, the ball was dropped. We gave in to the forces of equality and sloth, and in so doing, delayed humanity’s destiny as a multi-planetary civilisation for generations.

The tragedy is not that we failed to reach Mars.

It is that we nearly did, and then chose not to. We fecklessly poured endless resources into the gaping maw of Global Zimbabwe when we could have had Martian Rhodesia instead.

We could have built a whole new world of explosive vitality, human excellence, and immense prosperity—the very virtues of Rhodesia, on a similarly deadly but beautiful frontier—while also becoming immensely more wealthy, advanced, and energy-rich. Instead of that Martian Rhodesia, we are still without energy independence, and have wasted our civilizational prosperity not on fixing the favela but in parking Bentleys for a few oligarchs within it. That frittering away of civilizational vitality and prosperity must end. It’s time to reach back out to the stars.

By: A.J. Rees

A. J. Rees has been involved in the energy field for over 15 years and has worked in Europe, the Middle East, East Asia and Australia during this time. Located in Japan, he continues his work in the energy field with projects in nuclear decommissioning, recommissioning, renewable energy and building R&D connections between Japan and the rest of the world. He has previously had works published in energy, energy security and international relations journals as well as by the Lotus Eaters.

He had begun pushing musing and articles on energy matters on X @EnergyTrendsJPN or on Substack at Energy Trends JPN

Featured image credit: Stefan Kühn, CC BY-SA 3.0 <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/>, via Wikimedia Commons

For background on this, if you’re interested in electrification, the book Electrifying America is highly recommended. For the early history of it and some of the challenges, I quite liked Empires of Light

Also, if you’re interested in electrification, this is a fabulous article on it by Packy McCormick:

Details on that: https://history.state.gov/milestones/1969-1976/oil-embargo

Small Modular Reactor. Details on these here: http://www.iaea.org/newscenter/news/what-are-small-modular-reactors-smrs

Robert Zubrin discusses this some in his books, such as The Case for Space and The New World on Mars

Zubrin discusses this well in The New World on Mars

As Turner noted before the 19th century was out in The Frontier in American History

![[AUDIO] Abandoning Project Independence Gave Us Global Zimbabwe Instead of Martian Rhodesia](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!pRr6!,w_140,h_140,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-video.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fvideo_upload%2Fpost%2F185983901%2F2c87ed1c-4a33-4618-8737-ceb078af8039%2Ftranscoded-1769535255.png)

Hear, hear.

Let us not even discuss Chinese thorium salt reactors.