The High Cost of Consequences: Hillbilly Elegy by JD Vance

A Book Review

Thanks for reading and welcome back! Having read one of the books on this year’s reading list,1 and one quite relevant to the recent series on McKinley2 at that, I decided to go ahead and do a short review of it. Please let me know if you like this sort of content or not, and if not, I’ll avoid it moving forward. As always, if you enjoy this post or get something out of it, please tap the heart at the top or bottom of the page to show Substack that you like the post so it gets promoted and helps us grow. Thanks again!

What is the cost of bad policy? What are the consequences of viewing people as inputs that can be replaced at will, all over the world, by the global, corporate behemoths that have so much pull in our society? And what are the consequences of a culture and bad decision-making that lasts for generations?

Such is about what JD Vance wrote in his 2016 Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis. As described by him, the cost of those decisions and their consequences isn’t just economic. In fact, his immediate family had a reasonable shot at prosperity, and he turned out well in that regard. Rather, it’s personal. It’s a vast human toll that leaves untold millions living in squalor with little ambition or hope of improvement, even if they had ambition.

The Problem(s)

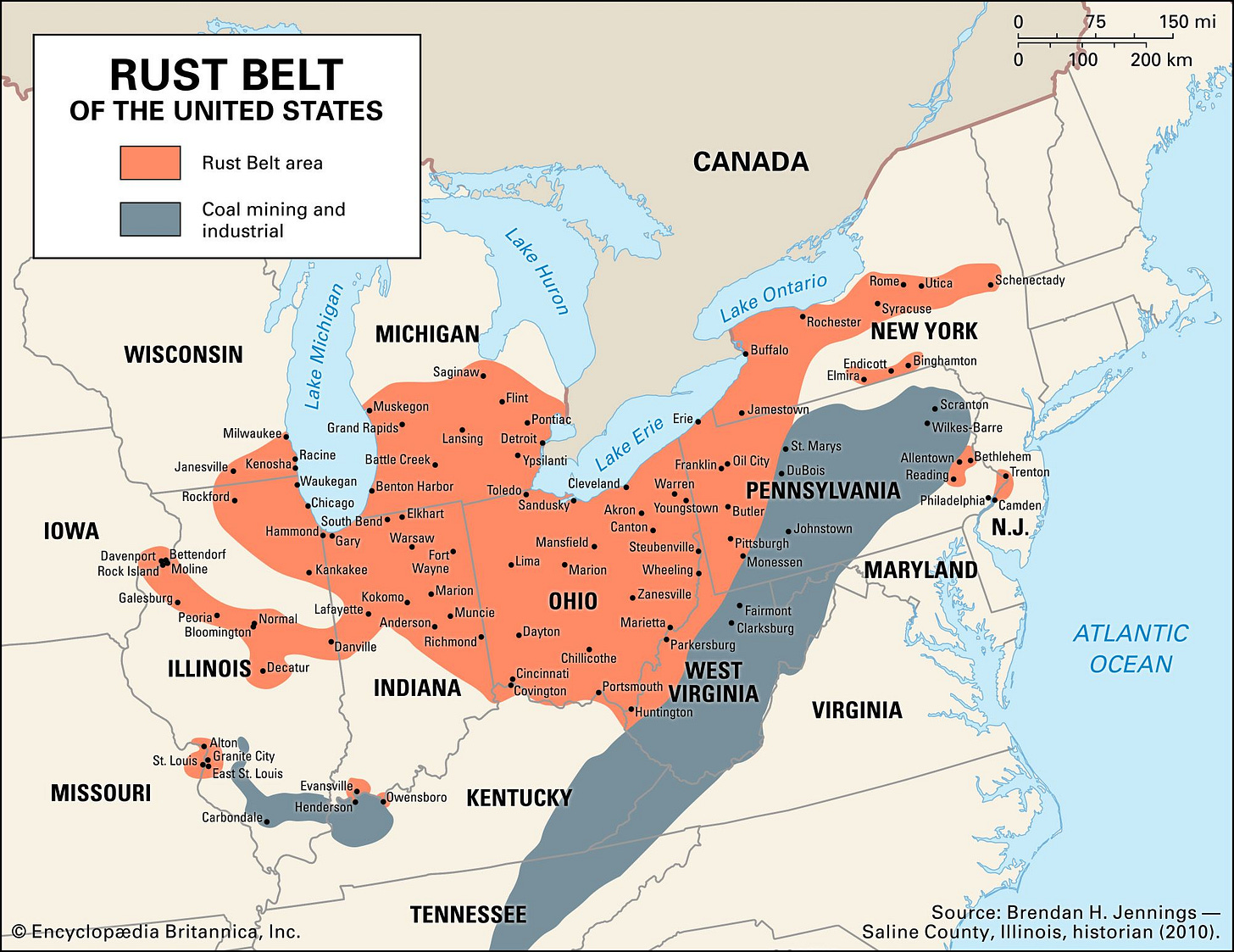

The “why?” behind that human toll is as multifaceted as might be expected of an area as vast as the one he describes in Hillbilly Elegy, essentially the blue and red shaded regions below of Appalachia and the Rust Belt, but Vances boils the cause down to two basic problems: globalization and culture.

Globalization

The globalization problem is one we all know, and thus easier to discuss. As Vance tells it, the vast corporations that had once provided the good jobs in the Rust Belt, in his hometown’s case a steel mill, were the ones that took the post-Cold War free(er) trade epoch on the chin.

Whereas the sort of policies that McKinley stood for and implemented3 helped them grow in prosperity, becoming gradually larger and more profitable, and thus hiring more people and providing them with good-paying, long-term jobs, the post-Cold War years saw that reverse. The formerly prosperous steel mills (the focus of Hillbilly Elegy is Armco, the Middleton, OH producer of automotive-grade steel) saw their profit margins slip as state-subsidized Chinese steel poured into the United States, automakers abroad started sending cars here en masse, and NAFTA led to American industry moving to Mexico to avoid labor and environmental regulations.

But the real problem for people like Vance wasn’t just that a steel plant was no longer thriving and needed a Japanese (Kawasaki Steel) bailout, however unpleasant that might have been for American industry.

It was that the decline of Armco wreaked secondary and teriary havoc for residents of Middleton, and indeed the region as a whole.

One is of the sort represented by JD Vance’s family. In its pre-globalization heyday, Armco (and companies like it) was an “economic savior” for people like Vance’s grandparents. Needing ever-more employees, it went into the hollers and hills of Appalachia to find men willing to work, and brought them to Ohio to work the mills in exchange for a steady, well-paying job. That, as Vance describes it, is what lifted his grandparents “from the hills of Kentucky into America’s middle class.” The same was true of innumerable families that saw the same economic salvation at the hands of similar industrial works. But now Ararmco, called AK Steel, doesn’t do that. Mass migration, the decline of industry generally, and similar issues stemming from out global world mean it needs fewer people, labor is cheap, and it must pay less to keep profits up. So instead of lifting impoverished but hard-working Americans into the middle class, it is struggling to hold onto life as a company while its employees struggle to remain in the lower middle class.

That was the secondary consequence of globalization. The tertiary one, as told by Vance, is that Armco stopped funding the sort of good works in the town it used to in its more profitable days, and with fewer employees the town dried up. So what had been a prosperous heartland town full of parks and the like sponsored by Armco turned into an ever-emptier place of shuttered stores, boarded windows, and crime.

In short, the cost of “cheaper” steel was the demolition of important structures within American society. For marginally cheaper input costs, we got far vaster social costs. But, as with most of the globalization, that cost was socialized rather than privatized; those using the cheaper imports profited while the rest of America dealt with untold thousands of declining towns like Middleton and the lack of opportunities for families like the Vances to rise from the lower to the middle class with blue-collar work.

Culture

It’s not the globalization aspect that makes Hillbilly Elegy interesting as a book. While Vance tells the personal aspect of that story well, he doesn’t dive particularly deep into the sort of economic data that could show the scale of the problem.

Rather, his memoir is interesting because it shows that you can’t escape modernity, and some cultures clash quite harshly with modernity.

Namely, his Scots-Irish background and the culture surrounding it clashes; nearly the entirety of the book consists of showing how the sort of culture his people were raised in, one of (as he broadly describes it at its worst) disdain for consistent work, predilection for substance abuse, and hair-trigger tempers lead to awful outcomes.

So, while Vance notes how the decline of Armco causes trouble for Middleton, he also shows how his acquaintances and Kentucky home were ravaged by families living on welfare and refusing to work while hitting the bottle and the drugs hard. Naturally, that leads to cascading consequences; it’s quite difficult to build a successful world on the back of pain pills and welfare.

This Vance describes in painful chapter after painful chapter. While his grandparents entered America’s middle class economically, they never adopted the characteristics of bourgeoise or Anglo culture, from temperance to avoiding avoidable violent interpersonal conflict. So everyone is vulgar, his grandpa took decades to beat drink, his (not thankfully sober) mother got hooked on pills while having a near-infinite succession of explosive, poorly-ending sexual relationships that caused chaos for her children - Vance and his sister - at home.

And they got off well. Both Vance and his sister managed to survive the poor culture and chaos and become successful and stable. But many didn’t.

What Vance takes pains to describe, based largely on his own experience, is that the rotten culture of the Scots-Irish at their worst conflicted harshly with the demands of modernity, and often it was their own failings rather than “society” that caused continual failure. While the aforementioned drink and pills are obvious examples, the bigger issue he describes is a refusal to do steady work: even when relatively good, well-paying blue-collar jobs were offered, Vance notes that his compatriots refused to do them because they’d rather rely on welfare and sit at home. It’s a harsh critique, but one that’s true of the worst cases, and is part of the reason why 40% of America doesn’t work and isn’t looking for work.4

Altogether that creates an extremely unideal scenario not unlike that present in the ghettos and rotten urban core of black America. Substance abuse, unstable sexual relationships often leading to illegitimate offspring, and proud acceptance of the welfare queen lifestyle are what Vance describes and what blacks in America are known for at their worst, something Vance notes as well.

The best summation of that situation comes from a haunting scene Vance describes: visiting his familial hometown in Kentucky after many years away, he explored the hills and hollers he once played in and found the area more decayed than ever. Scenes of dilapidated houses, drug-addicted neighbors, and general dysfunction culminate in his seeing a drunken father angrily glaring from the porch of a small, rotting house as a half-dozen pairs of scared, hollow children’s eyes peek out from the window of a dank room. His family members tell him the father not only doesn’t work and never has, but is proud of drunkenly collecting a welfare check rather than working.

What can be built on top of that rotten base? Very little, unfortunately.

Vast Costs

The toll of what Vance describes in Hillbilly Elegy is so vast that it’s hard to describe. Generally, however, the lesson is that the benefits are privatized, particularly the profits of opioid producers and low costs fo cheap foreign imports, while the costs are socialized. Rotting cities, vast unemployed populations, legions of opioid addicts, limited opportunities for long-term corporate employment, and all the rest described in depth by Vance is the socialized cost. American taxpayers and sovereign debt holders pay for the welfare programs, the Narcan, the $500 million Biden gave Armco,5 and all the rest. It’s a massive, expensive burden to bear that largely isn’t borne by those who caused the problems in the first place.

The trickier issue is the cultural aspect. The Scots-Irish at their best, as represented by some of the great men of history, namely Andrew Jackson, and now by men like JD Vance himself, are some of the greatest reservoirs of human capital in the world. That’s particularly true militarily. America wouldn’t have won a war without them and they still largely fill the ranks of the military’s combat arms units. But downsides are present as well, particularly when social conditions reward, or at least largely don’t punish, the natural consequences of going down the path of a culture’s given vices. For the Anglo-Saxons, those vices are largely spendthriftiness and caring too much about social standing, as seen in the glamor and waste of the Edwardian era and Gilded Age. For the Scots-Irish, those vices are unnecessary conflict, domestic chaos rather than tranquility, and substance abuse; such has been the case since the Percys ruled the North of England and fought the Scots border reivers (the group that became the Scots-Irish) and is still true today.

So, what’s the solution to the problems Vance describes?

All I can say is that if the benefits of the trendlines he notes are to be privatized, particularly the profits of globalization, then the costs should be as well. If an opioid maker of the Sackler mold hollows out Appalachian communities intentionally,6 it should bear the social burden, from Narcan and crime to welfare and joblessness, of that decision. If Chinese or Mexican industrial companies want to flood the American market with cheap steel and like goods, tariffs should be used to make them and those who in America who rely on them pay the cost of that community-hollowing decision. And so on. That would at least align incentives with costs.

If you found value in this article, please consider liking it using the button below, and upgrading to become a paid subscriber. That subscriber revenue supports the project and aids my attempts to share these important stories, and what they mean for you.

An excellent review of what external and internal factors have wreaked devastation in the white population of the rust belt where I was born and raised and still reside.

Mention was made in passing of the urban black underclass and here are some of my reflections on that issue.

For me to even raise issues related to race is to be immediately accused of racism. What the fuck, here goes anyway.

It’s far past time for society to quit pandering to the black community and to demand that it take the lead in correcting the problems that the black underclass faces. Here are a few suggestions.

There is a systematic lack of respect for education within that community. Tolerance of disruptive students by black school administrators and lack of effective discipline hinders learning in many black majority schools, stifling students’ potential achievement. The simple answer is to expel repeat offenders so that those who desire to learn can learn.

There is a casual acceptance of criminal behavior within many parts of the black community that results in a failure to cooperate with police in solving crimes. Until this is reversed there will be zero economic development within areas where they live.

Finally, someone must find a way to make all black fathers love and care for their children and especially their boy children. Young black men (15-34) are just 2% of the population and commit about half of the nation’s homicides. A rate fifty times higher than the average American. The lack of a father’s involvement in raising their sons is at the heart of this problem yet no one acknowledges it and seeks answers to it.

Where the hell are the middle and upper class blacks (and especially black politicians) who even publicly acknowledge this problem?

What are they waiting for?

https://aim4truth.org/2024/03/05/senator-jd-vances-paper-thin-biography-magical-financial-success-and-evident-insider-trading/

https://aim4truth.org/2024/07/17/j-d-vances-hindu-wife-usha-is-an-evident-handler-of-j-d-vance-for-the-british-pilgrims-society/