The Social Security Scam

"Gradually, then Suddenly" Comes to America's Retirement Program

Would you buy into an investment or annuity with an expected ~2% return1 that only works if the population and economy keep growing exponentially?2 No? Well, that’s why the gun of government is pointed squarely at your head with Social Security: it’s a terrible deal for taxpayers that is set up to fail as the total fertility rate decreases3 and the unfunded liabilities created by it4 are setting America up for a fiscal disaster.5

The sad truth of the matter is that the upcoming disaster was baked in from the start: the first welfare queen started collecting checks right after the program started cutting them despite putting in nearly nothing,6 a fact indicative of what the program really is and where it is heading.

Far from being a situation where you “put your money in” and “get it back,” Social Security is a massive Ponzi scheme that depends on the continual tax of the young for the benefit of the elderly,7 with it now being likely that those currently being taxed for the program won’t see a dime from it once they hit retirement age. And for those that say, “But it’s my money, I paid in!", SCOTUS has bad news for you: it ruled in Flemming v. Nestor that no one has a contractual right to Social Security benefits, so Congress can cut or amend “your” payment at will.8 In other words, Social Security is just a government check-cutting program like any other after you peel off the annuity-like veneer. Congress can limit how much is paid out at will, assuming it has the political will to do so, and it doesn’t matter a bit that you “paid into” the program for decades. That money has been long since spent anyway.

Of course, it didn’t have to be this way. The program could be run responsibly. It could be a way to ensure a minimum standard of living for the elderly without unduly burdening the young. But it’s not. It’s an underfunded monster ready to ruin the retirement dreams of millions.

What Is Social Security?

The common perception of Social Security is that it is a cut taken out of your paycheck every week, which is then put in some sort of government investment account and grows over time, if at a slower rate than in equities or a 60/40 portfolio, and gets paid back to you when you retire. That's not at all the case. In theory, it’s how such a program should work. The reality is quite different.

Roosevelt first concocted this Social Security program in the 1930s.9 Though Bismarck had led the way with such a program decades earlier10 and some states had welfare programs for the elderly,11 it was only in the 1930s America developed an old-age pension.

When first implemented, the idea was similar to old age insurance or an annuity (hence the propagandistic name of “premiums” for the Social Security taxes you pay). The government would tax your earnings now, invest the proceeds wisely, and when you retired, that money would be returned to you with interest.

So then the tax on incomes started being collected, with employers paying half and employees paying half (currently, the rate is 12.4%, though it started much higher). The program started chugging along in 1940 after being started in ‘35, helping out the elderly, as many elderly people at that time had no savings on which to rely.

But therein lies the problem: though the program had five years to build up something of a surplus, it wasn’t an insurance program or government-run investment service from the very start. Instead, it was a transfer of cash from the pockets of the young to the pockets of the elderly. But, with a growing population and expanding economy, the program seemed to be working.

In fact, even when the first massive cost of living adjustments raised the benefits in the 1950s, the program kept looking like it might work. Families were having children and raising them to be productive, American industry was on top of the world, incomes were rising (and with them, the “premiums” paid into Social Security), and people died, on average, relatively soon after they started taking Social Security checks. So, though the program was a Ponzi from the start, outside factors gave it the appearance of success.

But to those watching closely, the truth about the program should have been obvious from the start. Take, for example, the first Social Security payment ever issued.12 It, paid out on January 31st, 1940, went to Ida May Fuller of Ludlow, Vermont. Ida had, from ‘37-39. paid a total of $24.75 into the Social Security system. Her first check was $22.54, so nearly all she had paid in went right back out. She then continued collecting checks until her hundredth birthday, by which time she had collected a total of $22,882.92. Not a bad investment for $25.

And that’s the problem baked into Social Security: it’s a Ponzi scheme in which a growing population and/or economy (but preferably both) have to keep growing so that the tax dollars of the larger, younger cohort can later pay out the liabilities incurred by the program.13 Austrian economist Milton Friedman, describing the way the Ponzi scheme of Social Security works, said:14

Taxes paid by today’s workers are used to pay today’s retirees. If money is left over, it finances other government spending—though, to maintain the insurance fiction, paper entries are created in a “trust fund” that is simultaneously an asset and a liability of the government. When the benefits that are due exceed the proceeds from payroll taxes, as they will in the not very distant future, the difference will have to be financed by raising taxes, borrowing, creating money, or reducing other government spending. And that is true no matter how large the “trust fund.” The assurance that workers will receive benefits when they retire does not depend on the particular tax used to finance the benefits or on any “trust fund.” It depends solely on the expectation that future Congresses will honor promises made by earlier Congresses—what supporters call “a compact between the generations” and opponents call a Ponzi scheme.

Ms. Fuller collected about 1000x more than she put in. Flash forward to 2023, with all the millions of versions of Ms. Fuller collecting far more than you put in, and you end up with a nearly bankrupt Social Security program.15 Flash forward to 2033, and you have a completely bankrupt Social Security system, with what payments are made to come from the cash it collects rather than any saved pile of investment.s16 As Social Security itself reports: “The Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) Trust Fund will be able to pay 100 percent of total scheduled benefits until 2033, one year earlier than reported last year. At that time, the fund's reserves will become depleted and continuing program income will be sufficient to pay 77 percent of scheduled benefits.”17

Even as of now, the problem is quite severe. Each year, a trillion or so dollars is poured into the program from the Social Security tax on earnings, and each year, billions more dollars than are paid into it are paid out.

The following chart reveals18 the impending disaster of spending more money than is available.

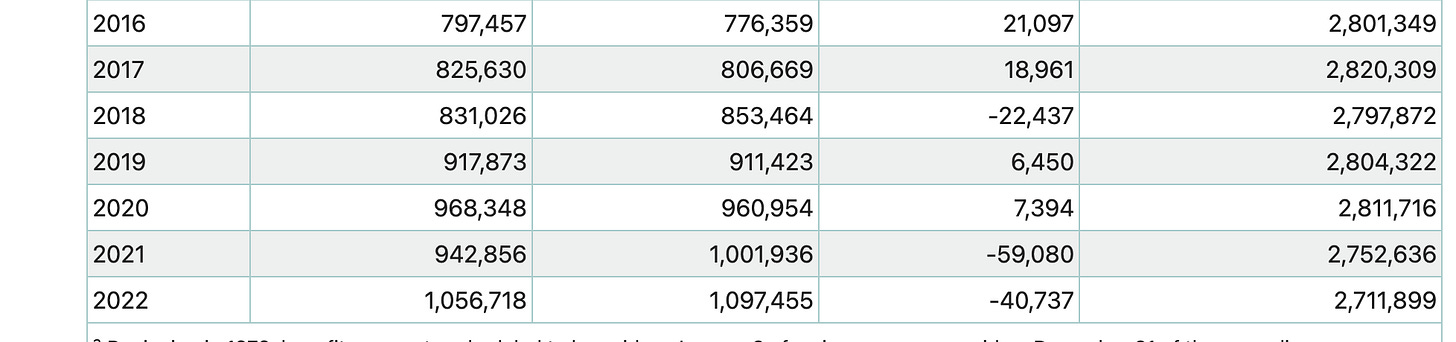

Take fiscal year 2023, as it’s the last fiscal year reported. In it, America collected $1.05 trillion in Social Security tax dollars.19 So that’s how much was paid into the program, and, if it functioned as people think, far less would be paid out. The money in the program would need to grow so that those currently paying in can eventually get their money back.

That’s not what is happening. Instead, in a year in which just $1.05 trillion was paid in, $1.097 trillion was paid out.20 The difference between the two might look like a small number, but it’s only because of the massive size of the program. If you look closer, that “little” 0.047 difference means that $47 billion more flowed out of the program than flowed into it. Put differently, $47 billion that should be being husbanded away for the future was spent for good.

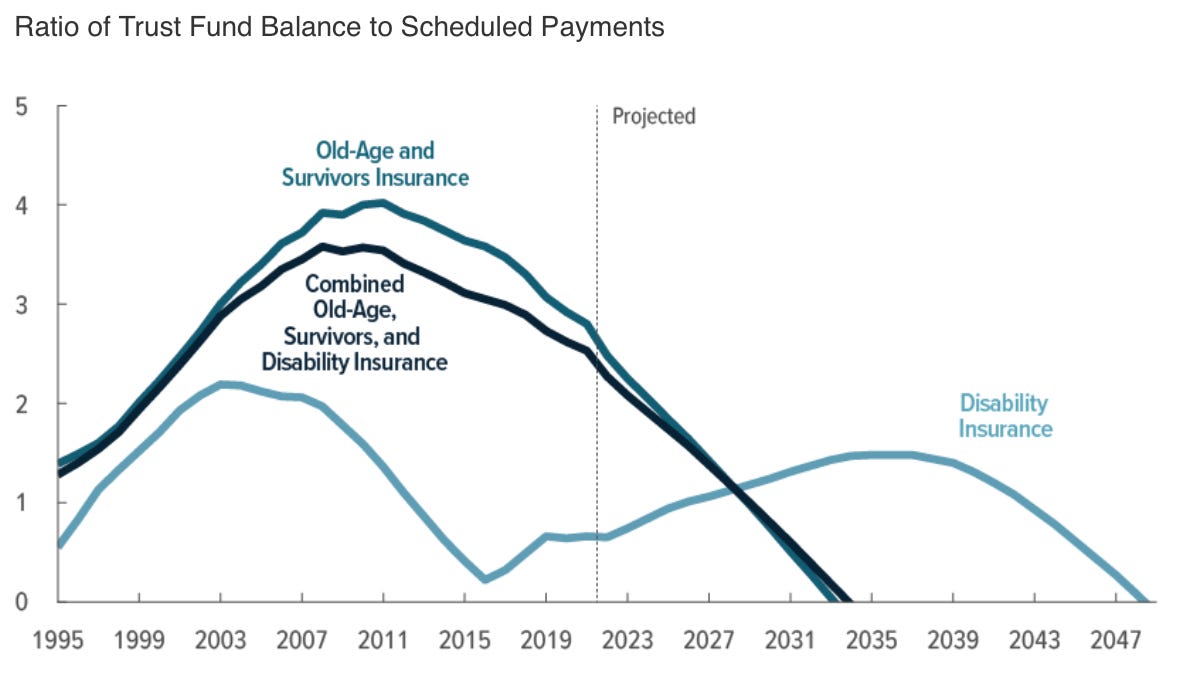

Another chart below illustrates21 the same problem in a different graphical style.

“But,” you might ask, “even if more is being paid out now, couldn’t that just be the savings from the past being paid out to the demographic bulge that is the Baby Boomer generation as it starts to retire?”

Unfortunately, that isn’t the case. Saving money isn’t our government’s strong suit, and the Social Security program is no different. Instead of a hefty and healthy “reserve” of income-producing investments producing the nearly $1.1 trillion paid out each year, or at least helping make up the shortfall in a sustainable way, the program is down to about two years of reserves. What’s going in is going out about as quickly as it comes in.

That problem can be seen in the low level at which the total Social Security savings fund sits: $2.7 trillion.22 That might sound like a lot of money, but when the program pays out ~$1.1 trillion every year, it’s far less than it looks like at first glance. It’s still less when automatic adjustments for inflation kick start to kick in and send the cost of the program screaming even higher.

Even without the added cost of inflation adjustments, the program would be out of money in just three short years, leaving tens of millions of Americans in the lurch.

The chart23 below shows the cold, hard facts if you doubt those numbers. The first column shows how much the program collected. The second column is how much it paid out. The third column shows the growing deficit. Then, if you look on the far right, that's the savings account. (Numbers shown are in millions of dollars.)

And in this chart, the “net interest,”24 or the difference between the cost of the program and how much it is bringing in, can be seen and compared with the overall amount brought in by it:

Three important issues immediately pop out in those two charts: 1) Social Security savings are down about $100 billion in just six years, 2) the net interest has been steadily widening for decades, and 3) the net interest balloons when there is a recession (look at 2008), as fewer people have jobs and so fewer people are paying into the program.

So, with taxes already painfully high, fewer people set to work as America’s shrinking fertility rate means fewer workers and taxpayers will be around in the near future, and a recession looming, the future of Social Security doesn’t look overly bright. In fact, current projections show the Social Security savings account goes to zero in about a decade25 years after decades of a widening shortfall. As Hemingway put it: “gradually, then suddenly.”26

According to the Congressional Budget Office, “[i]n 2034, Social Security revenues are projected to equal 77 percent of the program’s scheduled outlays, resulting in a 23 percent shortfall. Thus, CBO estimates that Social Security benefits would need to be reduced by 23 percent in 2034.”27 Not only does something have to happen, something absolutely will be happening in the next decade.

Could Anything Be Done to Fix It?

Had Social Security been properly managed from the start, with the “retirement age” being adjusted upwards as the average age of death rose, America wouldn’t be in its current predicament. The program would have been able to save money and so would be able to pay the current crop of retirees without falling apart completely.

But that’s not what happened. Instead of being revised upwards as Americans live longer, the Social Security retirement age of 65 more or less stuck: retirees get 70 percent of their full benefit if they claim at 62, 100 percent if they claim at 67, and 124 percent if they wait and claim at 70.28 And so the starting age more or less stayed the same as people lived for longer and longer and so drew down the Social Security savings account for longer and longer. Now the program is on the verge of bankruptcy and is eating the proverbial seed corn to keep the checks in the mail.

That leaves the government three options, none of which will be popular: it can dramatically raise the retirement age to stave off bankruptcy, dramatically expand the tax base by importing workers to make up for the fall-off in fertility, or jack up taxes so that more is paid into the program and more money can be saved.

All of those options are politically suicidal and so unlikely to be taken up by any DC politician.

Raising the retirement age would be the most effective long-term step, as that would give the program money to save in a sustainable way and limit the number of years people can claim Social Security checks, but would be entirely unpopular with the elderly voting bloc, which also happens to be the most politically involved and likely to vote voting bloc.

Then there is raising taxes, which DC could try but would lead to fierce criticism. Taxing the young to pay for the lifestyles of the old is unpopular in the best of times, and these aren’t the best of times. Further, forcing ever larger amounts of money into a non-productive government program is a terrible idea from an economic point of view. What could be used to invest in the future, build families, or pay for education would instead be wasted on yet another bloated and ailing welfare program. That hasn’t stopped the government before, but would be a powerful argument against a Social Security tax hike.

The other side of raising taxes would be slashing rates, which could also help the Social Security Administration muddle through without collapsing. It would have the added benefit of, theoretically, giving the program some breathing room to start saving money rather than spending it all on payouts immediately.

The Social Security Administration seems inclined toward the raising taxes or cutting benefits approach, writing, “The Social Security Board of Trustees project that changes equivalent to an immediate reduction in benefits of about 13 percent, or an immediate increase in the combined payroll tax rate from 12.4 percent to 14.4 percent, or some combination of these changes, would be sufficient to allow full payment of the scheduled benefits for the next 75 years.”29

And, finally, the government could keep doing what it is doing and let millions of new workers pour into the country in the hope that they will make up the difference. The problem is that illegal immigrants don’t pay taxes, and legal immigrants from the third world, from which a large enough population to make up for the TFR shortfall could theoretically come, are a massive drag on public finances.30 So that would just put the government deeper in debt and have no salubrious effect on the Social Security savings account. Further, the TFR of immigrants tends to fall once they assimilate into Western countries,31 so whatever theoretical benefit they provide would be short-lived.

There is one more option, and though perhaps the best in the long-term, it would be by far the most painful in the short term. That is to let the program fail and return to traditional ways of caring for the elderly in their dotage, as will be discussed below.

What Must Happen

Put most simply, the problem with Social Security is that it is paying far too much out. Bringing more in would simply take more money from those who need it to pay their bills, meaning increasing it would be devastating to lower-income families. With bringing more in all but impossible, all that is left is cutting how much is paid out, which could be done by decreasing benefits across the board or raising the retirement age.

The best solution might be simply letting Social Security wither on the vine and then die. As of 2033, the reserve will have run out and the program will be running on fumes, using the money coming in to make payments out. That will also make it more unpopular than ever, as the pretense of it “saving” your money for retirement will have vanished. Left will be the reality of the situation, which is that it’s a young-to-old wealth redistribution program, a fury-inducing fact when realized for those who can’t afford a home because a large portion of their paycheck is being sent to a retiree.

The anger sparked by that realization could be enough to get the program done away with when the reserve has run out. To replace it would be the traditional view of old age, which is that you should save money when young and that your children should help take care of you when you are old and infirm. Replacing a forced wealth redistribution scheme would be family and community bonds built around the ties that bind across generations. The painful tax, the uncertainty surrounding an unworkable system, and the wasted resources poured into a welfare scheme would be done away with. Replacing them would be the incentive for better and more productive investment, along with an incentive to stay close to one’s family and have a network of people with whom one can make it through old age.

Of course, with more Americans childless than ever,32 and many more estranged from their children, such a future could be near impossible to effect. Why would those who have no kids vote to remove a system that saves them from that imprudent decision?

That leaves either mass immigration, slashing payouts, raising the retirement age, or some combination thereof. Both, particularly some compromise between them, would be more likely to make it through Congress and have at least some chance of kicking the Social Security can down the road. Both, however, would leave the wasteful, poorly designed, and unjust system in place to continue leeching off the young.

Humanity made it for all of history, up until the 20th century, without a government-mandated old-age pension scheme. Why “must” we have one now, other than that special interests are addicted to the buckets of money poured down the bottomless well of that scheme?

Cheney admitted this in 2005, saying: “In fact, young workers who elect personal accounts can expect to receive a far higher rate of return on their money than the current system could ever afford to pay them. For example, if a 25-year-old invested $1,000 per year over 40 years at Social Security's 2 percent rate of return, in 40 years she would have over $61,000. But if she invested the money in the stock market, earning even its lowest historical rate of return, she would earn more than double that amount — $160,000. If the individual earned the average historical stock market rate of return, she would have more than $225,000 — or nearly four times the amount to be expected from Social Security.”

On Social Security not working as the fertility rate decreased: https://npg.org/projects/socialsecurity/pop&ss.htm; on TFR decreasing: https://www.prb.org/resources/why-is-the-u-s-birth-rate-declining/

https://www.cbo.gov/publication/58870

https://www.cbo.gov/publication/58870

https://www.cbo.gov/publication/58870