Pictures from the Past are Immensely Radicalizing

A Glimpse of a Different World

Welcome back, and thanks for reading! I caught a nasty cold of some sort with the wintry temperatures up here in the mountains of the Old Dominion, so today’s article is a bit shorter and more picture-heavy than most, though one that I still think you will find very interesting and with a good bit of food for thought. As always, please tap the heart to “like” this article if you get something out of it, as that is how Substack knows to promote it! Paid subscribers can listen to the audio version here:

Footage and pictures from the past really are something. The people are well-dressed and healthy-looking, not obese and in t-shirts or pajamas. The population is sociable and happy, not a rotten collection of migrants and criminals. Even where the footage shows relatively poor people, particularly by modern standards, it is evident that Western civilization was intact.

Take, for example, this video of English village life in the 50s:

This is even more pronounced in what footage of the world before the Great War exists. Europe, before the carnage in Flanders wrecked its soul, was atop Olympus, and footage of everyday life from that period shows it. This footage from Great Yorkshire Show in Leeds in 1902 is an example.1 Just look at the detailed and ornamental architecture, the care the average people there put into their everyday dress, the lack of crime and chaos, and all the other little things that make civilization more pleasant and constructive than barbarism:

The same is true of Paris, around the same time, for example:

Similarly, the architecture of the before times was impressive, inspiring, and glorious. Whether the towers and turrets of the Victorians, the symmetric splendor of the Edwardians, or the bold and powerful lines of the Art Deco era…monumental architecture hadn’t died, and what was built was not just pretty, but served as a reminder that a powerful and prosperous civilization was housed within the sturdy walls of what it built.

Take, for example, another example from Paris, the Palais Garnier, or Paris Opera House:

And there are the buildings of Chicago and New York:

The same is true of New York in its golden age:

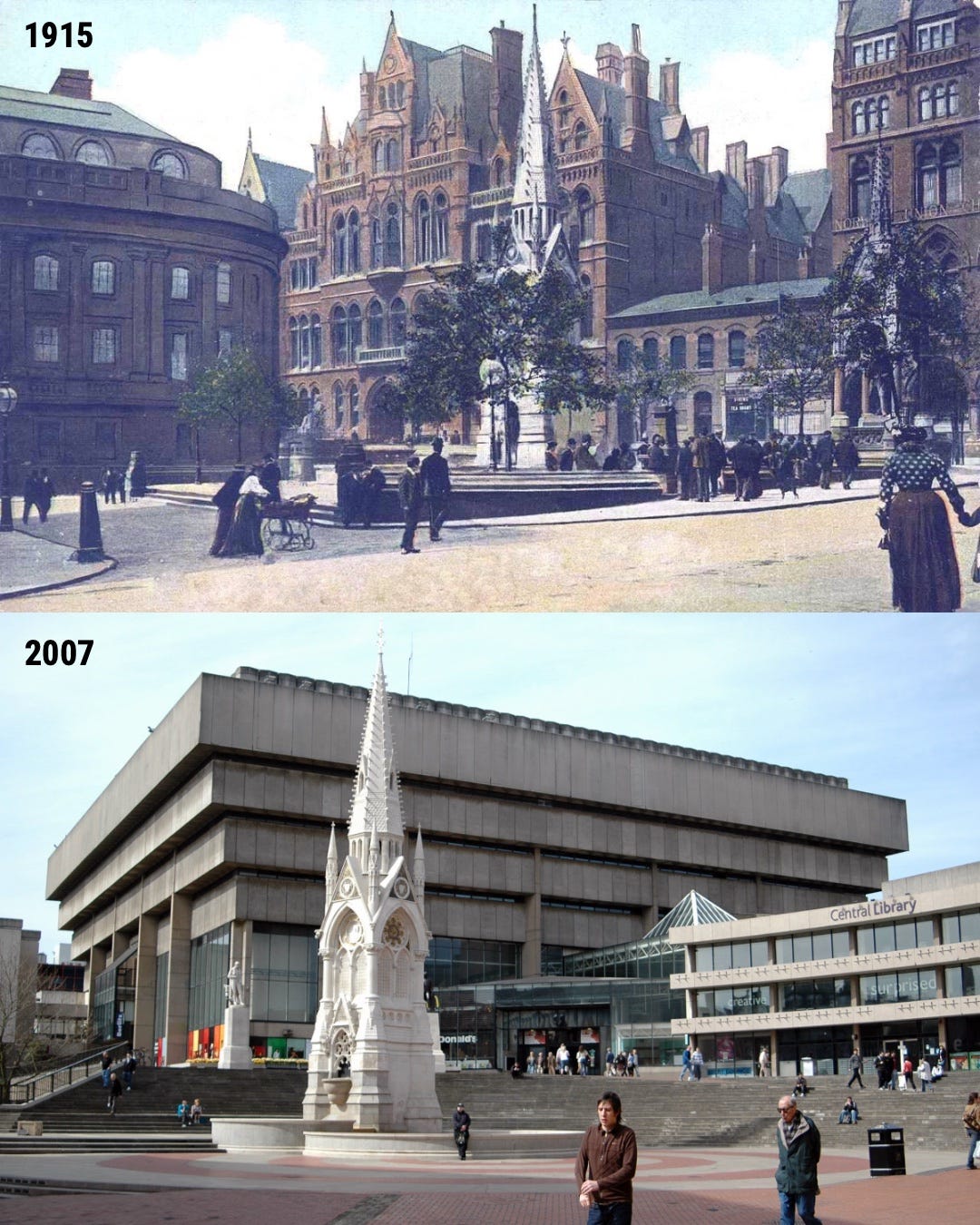

Now, that has been lost. Take, for example, the below three pictures of Chamberlain Square in Birmingham, England. The top photo shows what was built before the Great War. The middle photo shows what was built in the civilization-killing ‘60s. The third image is what it looks like today, when the Brutalist monstrosity was torn down and replaced by a marginally less horrendous one.

Meanwhile, here’s what life looks like in Birmingham, England, formerly one of the nation’s foremost industrial centers and now one of the epicenters of the “Grooming Gangs” scandal2:

As went the architecture, so went the city. Embracing the Third World’s characteristic values of equality, high time preference, and resistance to cultivation, while also importing the Third World, Birmingham became it. Now England’s second-largest city is a foreign slum.

The same sort of degradation and decay is visible across the world. Take, for example, the lack of detail that now goes into everyday objects. What used to be beautiful, and add just a little bit of beauty and refinement to the world, is gone. What has replaced it is some utilitarian object, probably made in a sweatshop abroad. The same is true of things like water towers. What was built was built beautifully, and built to last:

The Decline Is Real

All of this reflects very real and immense decline. As Yarvin notes in his Open Letter, “For example, according to official statistics, between 1900 and 1992 the crime rate in Great Britain, indictable offenses per capita known to the police, increased by a factor of 46. That’s not 46%. Oh, no. That’s 4600%.”

It’s no mere coincidence that the period that saw nearly every public place go from “beautiful” to “horrifyingly ugly and full of abominations” also saw an immense rise in crime: both are evidence of decline, and a showing of what evils are being heaped upon us.

This is obvious with crime. The anarchotyranny we now experience is obviously a demoralization tactic engaged in by despots, as Sam Francis noted when he invented the term.

Many have a harder time recognizing it with the beauty, or more accurately lack thereof, of public things. Vital societies on the ascent revel in creating beautiful and splendorous things, from the aqueducts of Rome to the country homes of England and their fabulous gardens, which were often open to the public.

This is reflected not just in the architecture, statuary, art, and the like—though it should be noted that no ascendant society has produced anything like modern art or brutalist architecture—but also in the dress and manners of the people. Even the poor in Victorian Britain and Gilded Age America wore suits when out in public, to show they too were ascending, improving themselves, and refining themselves; now, even our oligarchs wear t-shirts and jeans to show that they too are common men, no better than their fellows.

That is a demoralization tactic. When Mao was inflicting the Cultural Revolution upon China, he forced everyone to wear the same grey tunic.3 Some were more equal than others, getting tunics made of better material. But they looked the same. They were homogenizing, dreary, and equal. The result was a cultural disaster on par with the rest of the Cultural Revolution, with those forced out of their native dress and into the grey tunics so depressed by it all that the suicide rate jumped.4 The dreary uniformity was depressing to the point of death.

The same sort of thing is inflicted upon us now. New builds, whether homes or offices, are the same drab and dull collections of monotone whites and greys, perhaps with a bit of glass; gone is the suburban splendor of Edgbaston or the urban glory of the Horse Guards or Empire State Building. With the exception of the Ford Bronco and a few English car models, new cars largely lack the excitement and appeal of old; instead, the growing trend is toward all autos looking like some bug from the Orient crawling upon the asphalt, all in the name of efficiency. We’re hectored and told millionaires ought drive Camrys, clothes don’t matter so wearing a stained t-shirt for life is fine, and beauty is an inefficiency so it ought be extirpated in the name of cost savings and efficiency while the beauty of the natural world is filled with monotone apartment buildings for H-1B workers.

It is depressing. It is a sign of decline. It is intentional.

Such is why media from the past is so radicalizing. Theirs was a poorer world. Such is obviously true, and why their tenements were so much worse than our apartments, or even our Section 8 slums. Yet still they cared about something higher, and so they put in the hard work and immense expense necessary to turn their public areas, amenities, and infrastructure into something beautiful and uplifting.

Even on the budding American frontier, what towns and cities rose quickly built treed avenues on which the locals could promenade, greeting each other and showing off their refinement in public, as discussed in The Refinement of America. Such little amenities and opportunities to show and prove one’s taste and quality to one’s fellows, while also being around a physical world that uplifted rather than depressed the spirit was long a part of Western life, from the Forum of Augustus and Baths of Diocletian to the Metropolitan Opera in New York and the little everyday things that made the public spaces of the Belle Epoque world delightful and beautiful. That is what was stripped from us and our world. That is what was taken. That is what was replaced.

And what was it replaced by? Hordes of savages here to support pension plans a few years longer, and horrifically ugly structures justified by the claim that they are bit more comfortable or “practical” than refined, beautiful ones would be.5 That which require less of the mind and soul to comprehend and appreciate is built and made because it is easier.6 So, though the effect of those things—whether statuary or buildings, clothing or visual media—on both mind and soul is deleterious rather than uplifting, ease requires they be what is made and pushed upon us. It is depressing. It is intentional. It is radicalizing.

Our mission is to resurrect the world that used to be. To bring a bit of beauty into the world. To help make it a bit more cultivated, a bit more uplifting, a bit more inspiring, and a bit more excellent. This is what our ancestors did; they did not remain in sodhouse hovels and spartan log cabins forever, but rather used those as a means by which they slowly built civilization over generations. They started with the blank canvas of a prairie and primordial woods; we are starting with a decrepit and grim world of various modernisms, from art to architecture, that like the tough prairie before the bonanza farms must be plowed over and replaced by something better, something cultivated, something triumphant.

That will be an intergenerational struggle we will have to fight for as long as we are alive, or we will lose. Civilization is not built in a day, but it can be lost in one. The fight must continue.

If you found value in this article, please consider liking it using the button below, and upgrading to become a paid subscriber. That subscriber revenue supports the project and aids my attempts to share these important stories, and what they mean for you.

![[AUDIO] Media from the Past Is Radicalizing](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!VDL8!,w_140,h_140,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-video.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fvideo_upload%2Fpost%2F185550648%2Fd3618889-1d65-4446-9c29-c6bddc356628%2Ftranscoded-1769184465.png)

It's this stuff that radicalised me more than anything else. It is very embittering.

I often love seeing old pictures of my city before WWII. You can tell it was a different era. Even the poorest suburbs looked way better than modern downtowns with glass boxes. Beauty all around the city, everyone dressed like attending a dinner with the king. Now, after WWII, many destroyed buildings were replaced by Soviet brutalist ones. And when cities get infected like that, many people lose respect both for the country and themselves. There is no longer attachment to the city or the country.