El Salvador's Bukele Miracle Shows Rampant Crime is a Policy Choice

Your city is unlivable because of leftist "leadership," not fate

Crime Is Not Inexorable

“Wyrd bið ful aræd,” or “fate is inexorable,” is a famous line of Anglo-Saxon poetry1 made famous by historical fiction author Bernard Cornwell. Sadly, it’s more than a powerful line from time immemorable: it’s also the attitude that many Americans have taken, wrongly, of the state of America, particularly crime in her cities.

“Urban blight and rampant crime are inexorable,” the modern Anglo-Saxon might say while watching the Burger King burn and “fiery but mostly peaceful protesters” go on looting and carjacking sprees. But they shouldn’t.

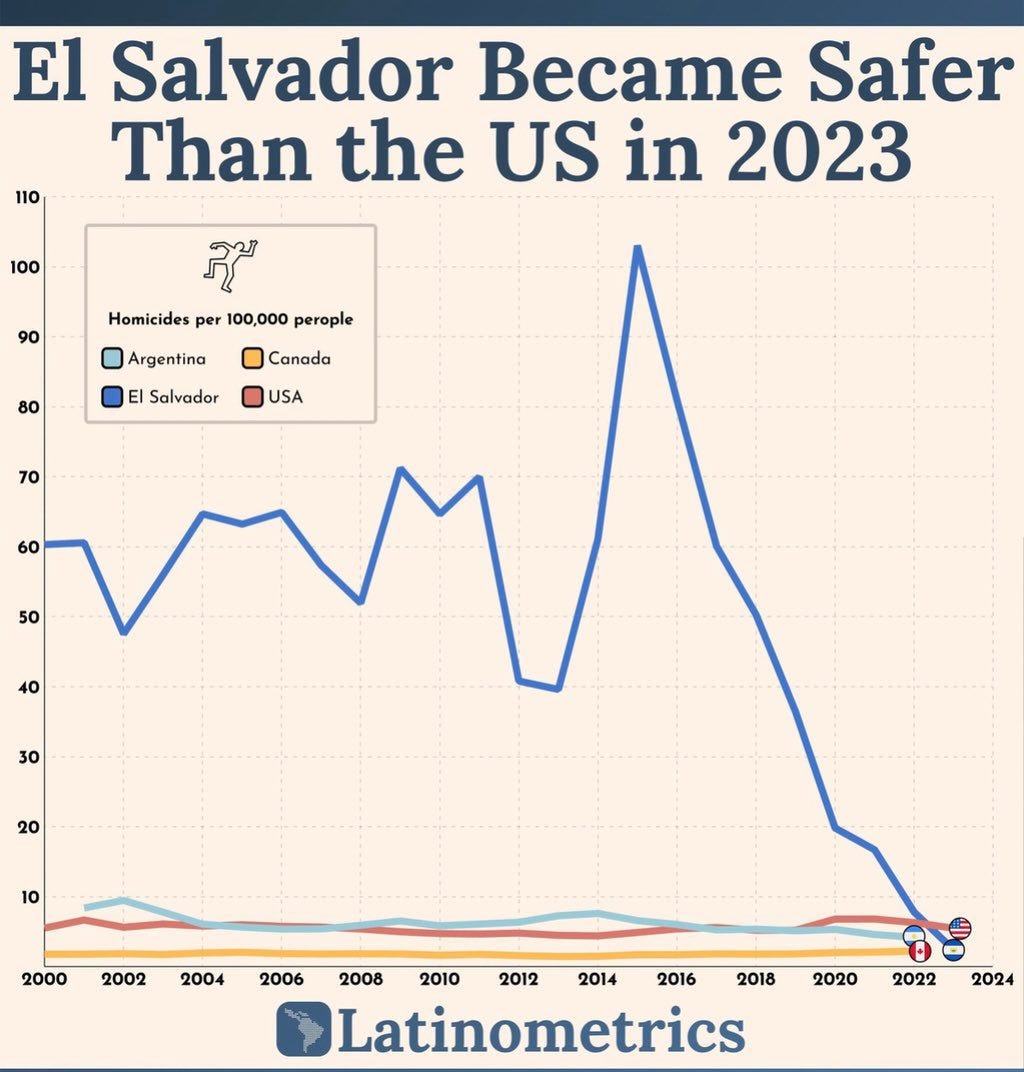

Crime, unlike the fate of Beowulf, is not inexorable. Rather, as Nayib Bukele’s transformation of El Salvador shows, crime is a choice. It can be stamped out. Quite easily, in fact. Our “leaders” just refuse to do so.

Note: Normally, we publish on Wednesday. However, given Bukele’s Sunday night win in the El Salvador elections, one marked by its magnitude,2 we thought it was more appropriate to publish this week’s article today. If you enjoy this article, check out our similar articles on Rhodesia, South Africa, and Libya.

The Bukele Miracle

When recently re-elected El Salvadorian President Nayib Bukele took power in 2019, El Salvador was what former President Donald Trump would have rightly called a “shithole country.” As even Freedom House, a DC-based, pro-”democracy” NGO tamely noted at the time, “corruption is a serious problem that undermines democracy and rule of law, and violence remains a grave problem.”3

“Grave problem” might be the understatement of the century. El Salvador, a tiny spit of lank in Central America, in 2015 was the murder capital of the world, thanks largely to lawlessness from Los Angeles spilling down to the much weaker country.4 The Guardian, reporting on the blood-drenched 2015 situation in August of that year, wrote (emphasis added):

Last Sunday was, briefly, the bloodiest day yet with 40 murders. But the record was beaten on Monday with 42 deaths, and surpassed again on Tuesday with 43. Even Iraq – with its civil war, suicide bombings, mortar attacks and US drone strikes – could not match such a lethal start to the week.

…

More than 3,830 people have been murdered in El Salvador this year. With one killing on average every hour, August is on course to be the deadliest month since the 1992 peace accord. On current trends, the homicide rate will pass 90 per 100,000 people in 2015, overtaking that of Honduras as the highest in the world (not including battlegrounds like Syria). This would make El Salvador almost 20 times deadlier than the US and 90 times deadlier than the UK.

To some extent, violence has been normalised. For much of its history, this small country has suffered levels of murder unimaginable almost anywhere else outside of wartime, primarily due to turf battles and revenge killings by the Mara Salvatrucha (better known as MS-13), and Barrio 18, which is split into two factions.

These “mara” have their origins in the gangs of Los Angeles. When El Salvador’s civil war ended in 1992, the US deported thousands of illegal migrants back to their home country. Many brought back the violent street culture and mutual hatred that had shaped their existence in California. Over the past two decades, they have grown, evolved and wreaked more carnage in El Salvador due to the weak government, dire inequality and a historical national tendency towards violence both in institutions and households.

To put 90 homicides per 100,000 people in perspective, the most dangerous city in America is Memphis, TN. It has 24 murders per 100,000 people.5 Yet worse, the Guardian’s mid-year estimate for El Salvador proved overly optimistic. The actual 2015 homicide rate was well over 100 per 100,000 people.6

Things were slightly better when Bukele took over, but not by much. In 2018, the year before he became president, the murder rate was still a painfully high 53.31 per 100,000,7 more than double that of Memphis.

Further, it wasn’t just the murder rate making life in the tiny nation unbearable. In addition to the streets being washed with blood, the tattoo-covered MS-13 and Barrio 18 gang members held the entire country in their death grip. As Foreign Policy noted in an article aptly titled “A Nation Held Hostage”:8

The rival gangs MS-13 and La 18 control or influence every facet of life in El Salvador, making the small Central American nation the world’s most dangerous place outside a war zone.

…

The gang culture that has evolved since the end of the 12-year-long civil war in 1992 is unmatched for its brutality and scale of violence. The country’s defense ministry estimates that as many as 500,000 Salvadorans are involved in gangs—in a country of 6.5 million—either through direct participation or through coercion and extortion by relatives, amounting to 8 percent of the population.

El Salvador is characterized not only by widespread violence but also by the brutality with which the violence is carried out. After firearms, machetes are the most common murder weapon. Often, the aim is not just to kill, but to torture, maim, and dismember the victim. The emergence of an intricate gang culture with its own traditions, rules, and structures has transformed the act of killing into a ritual, filled with intentional references to sadism and satanism.

Videos and stories of these killings, which usually involve a group of laughing gang members gleefully hacking away at the body parts of a victim and removing organs, have paralyzed Salvadoran society, creating a pervasive atmosphere of fear: Anybody can be an informer for a gang, nobody is safe, any street can become a crime scene, anybody can disappear. Public killings are common, accounting for nearly 40 percent of all murders.

…

Today, in many Salvadoran cities, it is impossible to cross the street due to the boundaries of rival gangs’ territory. When entering a new neighborhood by car, visitors often have to flash their lights or roll windows down to indicate allegiance to the gang that controls it—or face violence.

…

Traditionally, both major gangs have operated in a decentralized way, usually financed through daily extortion promises, which range from just $2 to $3 for small businesses and $5 to $20 for medium-sized businesses and distributors. However, through combined extortion of 70 percent of all businesses in the country, the gangs collect large amounts of money, with estimated revenues of $31.2 million for MS-13. The money spent because of gangs, either through extortion or buying private security, combined with the money lost because of violence, amounts to a staggering $4 billion per year, about 15 percent of the country’s GDP, according to a report from the Central Reserve Bank.

The entire nation was held hostage by brutal gangs that bled the economy with extortion schemes and the citizenry to death with machete blades and brutal displays of violence. It was hell on earth, and the ruling regime was complicit. Living in their barbed-wire-surrounded, walled compounds, the ruling elites hid behind their guards and moats and struck deals with the gangs rather than stand up to them.9

Then, a miracle happened. In 2019, President Nayib Bukele was elected. Unlike the corrupt leaders of days past, Bukele went to war with the gangs. He vowed to eradicate them within four years10 and then set to work to fulfill that vow. Results could be seen within months, as Foreign Policy reported11:

During his first 150 days in office, the murder rate has dropped precipitously. The first seven months of 2019 were the least violent months in the last 15 years (except for 2013 and the 2012 gang truce). On July 31, not a single killing was recorded—only the eighth murder-free day in 19 years.

Predictably, the usual suspects were outraged. Rather than feel sympathy for the ordinary people of El Salvador, living as they were under the bootheel of machete-wielding gangs, pro-anarcho-tyranny journalists and NGOs from the West declared Bukele to be a “dictator” who was abusing “human rights” with his anti-gang crackdown. “Civil and human rights organizations have criticized the situation, citing widespread abuses, including deaths of dozens in detention,” the AP reported, for example.12

The US Embassy for the Biden Regime joined in as well, writing, “Significant human rights issues included: allegations of unlawful killings of suspected gang members and others by security forces; forced disappearances by military personnel; torture by security forces; arbitrary arrest and detention by the PNC; harsh and life-threatening prison conditions; serious problems with the independence of the judiciary; widespread government corruption; violence against women and girls that was inconsistently addressed by authorities; security force violence against lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex (LGBTI) individuals; and children engaged in the worst forms of child labor.”13

Nevertheless, he persisted. Bukele had vowed to eradicate the gang problem within four years of 2019 and, miraculously, managed to fulfill that vow. The real turning point in his war on organized crime came after the gangs went on the offensive in 2022. Instead of engaging in yet another round of fruitless negotiations, Bukele fought back. He declared a state of emergency14 that gave him broad legal powers to wage war on the gangs and stamp them out for good, then used that power with urgency to arrest about 74,000 gang members over the course of 2022 and 2023.15 The New Yorker, breathlessly reporting on the El Salvadorian “authoritarian” and his anti-gang tactics, wrote (emphasis added):16

Just after midnight on the second day of the homicide spike, the National Assembly, which Bukele’s party controls, instituted a “state of exception,” under which authorities could arrest anyone they considered suspicious. Detainees were not entitled to a legal defense. The right to gather in groups larger than two was suspended, and all minors would be tried as adults. On his Twitter account, Bukele, who is forty-one years old and has an approval rating of more than eighty per cent, shared a running tally of the arrests that followed, along with scabrous commentary, posting photographs of tattooed men in handcuffs and underwear (“little angels”), some of whom appeared to have been roughed up (“He must have been eating fries with ketchup”). Critics of the new policy—whether common citizens, journalists, or foreign governments—supported “the terrorists,” he wrote.

Describing the locked-down conditions inside the jails, the US Embassy wrote (emphasis added):17

As of August 29, extraordinary measures designed to interrupt gang communications and coordination between imprisoned leaders and gang members outside the prisons were in effect in eight prisons. The measures reduced the smuggling of weapons, drugs, and other contraband such as cell phones and SIM cards into prisons; however, contraband remained a problem, at times with complicity from prison officials.

On June 20, the minister of justice and the director of prisons imposed a state of emergency in 19 prisons at President Bukele’s request and as part of his security program, the Plan for Territorial Control. Under the state of emergency, prisoners were not able to receive any type of visit, were confined to their cells 24 hours a day, were not permitted to visit recreational or medical facilities except in extraordinary circumstances, did not receive mail or have access to radios or televisions, and did not engage in work activities. In addition, beginning on June 21, the minister and the director used their legal authority to completely disable cell phone signals inside and around prisons. The Court of Penitentiary Surveillance and Penalty Execution subsequently ratified the state of emergency. On September 2, President Bukele instructed the minister and the director to lift the state of emergency in prisons. Inmates’ right to receive visitors was gradually restored in prisons that did not hold inmates affiliated with gangs.

A video posted by Bukele18 showed much of that to be true. It shows the scantily clad prisoners being frog-marched into prison as baton-wielding riot police watch on, sending the message that what the old regime tolerated, crime and gang activity, will no longer be tolerated. Watch it here:

Further, Bukele took little note of his critics during the process. Responding to the claims that he is a dictator, he declared, as tens of thousands of fans roared with applause, “They say we live in a dictatorship . . . ask bus passengers, people eating in restaurants, waiters. Ask whomever you want. Here in El Salvador, you can go anywhere and it’s totally safe. … Ask them what they think of El Salvador, what they think of our government, what they think of our supposed dictatorship.”19

The result of his dismissive attitude toward leftists in the West and the feelings of gang members is that he defeated crime in the country, pushing crime down to 2.4 per 100,000.20 What was once the murder capital of the world is now far safer than most of the world, including the United States.

All it took was a few thousand arrests. He didn’t even need to use Napoleon’s whiff of grapeshot, much less the bloody tactics of Pinochet and others who have restored order with an iron fist. He simply needed to crack down on criminals, ensure no leftist judge or NGO stopped him from ushering the gang members into jail, and then toss away the key to keep them in there for decades. That moderate, prudent policy solved an intractable crime problem and made him one of the world’s few extremely popular leaders; much as CNN and others clutch their pearls at his tactics, the long-oppressed common people of El Salvador love him for how he saved their country.21

Crime Is a Choice

While America is nowhere near as violent as El Salvador, it struggles with many similar problems. Violent crime has made cities unliveable,22 looting and rampant retail theft have shut down once-famous businesses across soft-on-crime cities,23 and omnipresent public drug use and homelessness make city streets dirty biohazards.24

San Francisco used to be beautiful and full of incredible shops at which one could peruse luxury goods in perfect safety and an appealing environment. Now, it’s closer to Haiti than El Salvador. Union Station used to be one of the few remaining beautiful train stations in America. Now it’s swamped with hobos and looks like a cross between a favela and a Dark Age village in the ruins of Rome. The list goes on and on: Atlanta, Baltimore, Detroit, St. Louis, and Memphis were all, at one point in their history, gems of cities. They were beautiful, clean, and on the upswing. Now? Not so much. In modern American cities, remembering to lock the windows, keep a round in the chamber, and not stop at stop signs where carjackers can get you is a more relevant rule of thumb than the sartorial rule of remembering not to wear brown into town.25

All of that could be stopped in an instant. A few years at most. Nayib Bukele, the leader of a small country in Central America with few resources, decades of violence and unrest under its belt, and nearly a tenth of its population with some gang affiliation managed to solve the problem in four years.26 America, with far more resources to deploy, could solve its crime problem in far less time. Gavin Newsom showed as much when he cleaned up San Francisco for President Xi of China,27 and Giuliani made New York liveable28 until his liberal successors threw away all his progress.

But our “leaders” refuse to do so. As the US Embassy’s pearl-clutching post about Bukele’s gang policy shows, the government refuses to contemplate doing what is necessary to sweep the criminals off the streets and make life liveable for normal people once again. Perhaps that’s because of a deliberate policy of anarcho-tyranny,29 maybe it’s because of cowardice, maybe some mixture, but the effect is the same: Americans must suffer under a horrific crime burden not because crime is inexorable, but because their government refuses to follow in Bukele’s footsteps and solve the problem.