How Britain Became a Hellhole

A Narrative, and a Reading List

Welcome back, friends, and thanks for reading! Today’s article is somewhat different than most of the content, but is something I have been asked for repeatedly in the wake of my article in “The Islander,” a magazine run by Carl Benjamin and the Lotus Eaters, about Britain’s nobility and its abdication of duty. Given present circumstances over there, along with the interest stemming from the magazine article, I figured it was worth doing. However, it doesn’t translate well to audio because of the unique format, so I did not do an audio version. Enjoy! And as always, please tap the heart icon to “like” this article, as that is how the algorithm knows how to promote it.

Why is Britain in such a pitiful state? How did the island land that once ruled a quarter of the world’s surface go from being the imperial titan all others envied to a miserable backwater known mainly for regulating kitchen knives and allowing Muslim invaders to rape its teenage girls?

My contention is that Britain declared war upon itself with the Parliament Bill, and that campaign of anti-civilizational envy and social strife that the bill epitomized and encouraged is a disaster from which Britain has not recovered (I have discussed this in-depth on X, let me know in the comments if you’d like me to elaborate in an article).

In short, what we have seen is Britain go from being full of civilizational confidence and a focus on excellence to a land dominated by dreary bureaucracy and “men without chests”.1 That is to say: Britain has a ruling elite and a bevy of lackeys under them, but it no longer has leaders; they were crushed and replaced with the stifling grey bureaucracy that now rules the land, with predictably poor results.

Much has played a role in that, from the World Wars to the Great Depression, American Cold War policy to death taxes and managerialism. But all of it, from the Grooming Gangs to suicidally dumb energy policy,2 is, I think, the result of the push toward egalitarian mass democracy with no restraints that the Parliament Bill symbolized, and the resultant poverty, dysfunction, and death of standards that came with such a political environment.

In this article, I’ll explain how that happened, with the article structured around a reading list. While normally I would just do a narrative article, I have now been asked repeatedly for an in-depth reading list on this subject, so I hope you find it useful. In each section, I’ll provide my narrative story of what happened over the years, and then an annotated reading list providing books you should read on the subject and why, in descending order of importance. If you’d prefer to skip around and only read the narrative bits, just use the navigation bar at the side to skip the reading lists, though I think you’ll find the details in the reading list sections useful.

The Olympian Old World, and What It Was Like

It is important to recognize that things were not always this way. While conditions have been better and worse at times as agrarian prosperity rose and fell with the seasons while industrial prosperity waited with bated breath for the signs of a panic, there was a long era in which Britain was governed well by men who generally had its best interests at heart, and were neither rival gangs of warring barons or dreary bureaucrats with little love of their people and even less honor.

That period was, roughly, from the Glorious Revolution until the Parliament Bill and Great War, or the late 17th century until the end of the first decade of the 20th century. There were good rulers before, of course; some of the Plantagenets were quite good kings. But that rule was largely different than what followed the tumult, tyranny, and disaster that culminated with the Civil War and the end of the Stuarts.

So, what was Britain like in the period described, that roughly two-century period that saw England rise from a war-wracked backwater too dysfunctional to affect Europe’s affairs to its position as the world’s leading empire?

It was an unequal, hierarchical society that nevertheless encouraged excellence and had a permeable enough upper crust to allow the best to enter it and the worst to fall out of it. That upper crust was then called upon to not recline in luxurious leisure, but instead use its resources to serve the land—in county administration as Justices of the Peace, in national administration in Parliament, in imperial administration in the Colonial Office, or in national service as an officer in the military. That is to say, there was a hereditary elite, but it was expected to think of its duties rather than just its privileges.

Further, in many respects, it struck the best tradeoffs between contradictory positions. It was tradition-oriented, with the great families living in the same splendorous country castles as their ancestors and knowing all the details of their noble lineages, while also being much more willing to get along with the new economy and pursue industrial success than their similarly tradition-oriented continental peers. The fruits of its newfound wealth were unevenly distributed, but still, the poor were far better off in Merry Old England than on the continent; even critics of the ruling elite admitted as much, being horrified by the hovels in which continental serfs and laborers lived. It was hostile to a large, standing military establishment…yet its army ruled a quarter of the world and its navy all the world’s waves.

That’s not to say things were perfect. Life at the bottom was often terrible, particularly once industrialization hit society hard, and many at the top were effete and feckless rather than men who lived for duty.

But, on the whole, life was generally good, particularly on a relative basis. The country estates pulled enough wealth into investments in farms and villages that they were profitable and prosperous, and kept the owners of such estates focused on the lives and concerns of their rural constituents. Budding aristocratic involvement in ownership and funding of industrial concerns, and political involvement alongside that, tended to temper the demands placed on workers, particularly as the 19th century wore on. Churches were well-funded and attended regularly, social mores kept most members of most classes from behaving abominably, couples got married rather than having repeated out-of-wedlock births, and so on. Things were not perfect, but were generally good.

Further, the decades of rising prosperity and good conditions encouraged a different view of the world. Englishmen could strike out and make their fortune, whether trapping furs in Canada, growing tea in India, taking over their own private kingdom like the Brookes, or even getting lucky with prize money in the navy. Options were open, and so those who wanted to do something better than the life that fate originally had in store for them could. This tended towards lowering social temperatures—avoiding anything like the bloody underclass uprising that was the French Revolution—and encouraging productive action, as those who succeeded could enter the upper crust and leave their families far better off. This was in contrast to Britain’s European peers, which had far less permeable and more settled elites.

Thus, by the end of this period, life in Britain was quite nice. Religion was intact, opportunity abounded for those who tried to seek it, taxes were low, and those with great wealth were expected to use it toward the end of aiding their countrymen and keeping Britain from harm. Further, life at the apogee of this civilizational stage could be and generally was quite pleasant, as the famous Keynes quote notes:

"The inhabitant of London could order by telephone, sipping his morning tea in bed, the various products of the whole earth, in such quantity as he might see fit, and reasonably expect their early delivery upon his doorstep; he could at the same time and by the same means adventure his wealth in the natural resources and new enterprises of any quarter of the world, and share, without exertion or even trouble, in their prospective fruits and advantages; or he could decide to couple the security of his fortunes with the good faith of the townspeople of any substantial municipality in any continent that fancy or information might recommend."

All was not perfect. But conditions were relatively good, and looking better. British industrial power was strong, and the benefits of empire opened wide markets that could be exploited for the benefit of workers and capitalists at home. London was the world’s financial hub, giving it prime importance in international affairs. Belief in God and King remained strong, and provided the human capital conditions, political impetus, and civilizational self-confidence necessary for keeping Britain safe and the empire not just intact but expanding.

No Grooming Gangs would have dared descend on Britain’s shores in this period, and had they done so, the ruling elite would have quickly ensured their deaths.

Note: This article contains numerous Amazon links, to the books described. I am an Amazon affiliate and will receive a small commission, at no cost to you, if you use them, whether these links below or the ones that follow in later sections.

A Reading List for this Period

The Aristocracy in England, 1660-1914 by J. V. Beckett: This period was defined by the actions, attitudes, and lifestyles of the upper crust—the leading 1% that controlled most of the resources, provided nearly all of the political and military leadership, and set the cultural standard for most of the classes below it. Beckett does a fantastic job of showing the duty aspect of the equation, along with how that played out in political decisions, investments, and the like.

1913 by Charles Emmerson and The Proud Tower by Barbara Tuchman: It is important to remember that the pre-World War I world was a different one than ours in most ways, good and bad. It had injustices, of course, though ones much tamer than the Grooming Gangs. Life was tougher, but also filled with much more beauty and splendor, including for those on the outside looking in. The safety net was smaller to nonexistent, but those with agency and capability could rise to prominence and great wealth in the relative blink of an eye. Both of these books show that quite well, and present a fair portrait of the Old World as it was, good and bad (though I think with much more of the former than the latter).

Aristocratic Enterprise: The Fitzwilliam Industrial Undertakings, 1795-1857 by Mee and Cardiff and the Marquesses of Bute by Davies: Many promote the oft-repeated idea that the British elite, namely the gentry and aristocracy, saw industrial involvement is grimy and so eschewed it, ignoring everything from coal mines to ports in the name of preserving their agrarian bliss. That attitude didn’t really exist, other than in that they saw it as their duty to lead rather than work. When it came to the investments that built Britain’s dominance in the period—the steamer fleets and ports to service them, the mines that provided the coal and iron needed for industry, the railroads and canals that carried the industrial goods across the country at low cost—the elite was deeply involved in providing the funding. Further, when and where involved, they tended to exercise a restraining function on the generally rapacious industrialists. The Fitzwilliams and their mines are a good example: while they ran the mines to make a profit, they also focused on keeping the miners safe and in relatively good living conditions; they were the leaders in safety innovations, workplace safety regulations, and the like, and the miners loved them for it. These two books show how aristocratic involvement in the economies of their times were opportunities for noblesse oblige, and were often taken.

Coke of Norfolk (1754-1842): A Biography by Martins: Much as the ruling elite was involved in industrial investment and expansion, its main preserve remained the landed estate. But, far from just resting on their laurels, most were involved in agricultural reform. Field drainage, rotating crops, enclosure, and the like are common sense now and provided the bumper crops necessary for the Industrial Revolution, but required vast amounts of capital to try for the first time, in the Agricultural Revolution. This was where the prudence and noblesse oblige of the ruling elite shone through best, and it was Coke of Norfolk who was the leader of the agricultural reform effort. This is a fabulous book that describes his efforts.

The British Gentry, the Southern Planter, and the Northern Family Farmer: Agriculture and Sectional Antagonism in North America by Huston: A persistent complaint I get when I speak positively about the British aristocracy is that its success came at the expense of yeomen farmers. For one, that’s not really true: in reality, that class tended toward turning into lower gentry during the Regency period, as grain prices were high and so they could afford to accumulate more assets (discussed in the recommendation below). More importantly, that critique misses the tradeoff between a yeoman-focused agricultural sphere and a gentry-dominated one. A yeoman-focused system breeds independence, but lacks the proper resources to plow into the land when agricultural advancements crop up. Field drainage, enclosure, purchasing mechanized equipment, and the like are all immensely expensive. Someone with vast resources has to pay for that, or the farmer will be indebted and fall into ruin when crop prices fall. A gentry/aristocracy-led system provides the financial resources necessary for that, and means land is held in large enough blocks that advancements such as mechanization make financial sense. This book shows that in detail, doing so by contrasting the British system with the two American systems.

The World We Have Lost by Peter Laslett: To understand this period, it is necessary to first understand what life was like in the waning days before the Industrial Revolution. This is by far the best book on the subject, and provides an in-depth study of the social structures in that world. That, in turn, makes understanding the semi-feudal world that still existed until 1912 or so much more comprehensible.

Victorian Duke: The Life of Hugh Lupus Grosvenor First Duke of Westminster by Huxley: This is a fun, short read that captures the splendor of the period as shown by one of its greatest beneficiaries. It also shows how that translated into a sense of duty, noblesse oblige, and honor.

The British Aristocracy by Mark Bence-Jones: A fabulous, short read, this one puts the aristocracy in social context and shows its good and bad sides. It’s less detailed than Beckett’s work, but is a superb primer, and is a good read to recommend to those who are vaguely interested in but skeptical of the whole idea, as it shows the positive sides quite well and puts them in context alongside the relatively smaller faults.

European Landed Elites in the Nineteenth Century by David Spring: This book puts the British landed elite—gentry and aristocracy—in the context of their contemporaries in continental Europe at the time, showing by comparison how they were largely much more prudent, successful, and committed to duty. It’s an interesting and short book.

The Victorian Countryside (Vols I and II) by Mingay and English Country Life 1780-1830 by Bovill: What was life actually like in the country world romanticised by everyone from Jane Austen to J.P. Morgan? Wonderful for the top, great for the middle and lower middle (farmers, shop owners, etc), and anywhere from pleasant to wretched for the bottom. These books show the reality of life, good and bad, and the signal fact that a land owner who did his duty and invested for the benefit of the laborers could make their lives significantly better with a relatively small outlay.

The Growth of Victorian London by Olsen: While life in the countryside is often romanticized, life in the city is often demonized. This shows the reality of it, good and bad, and presents an interesting contrast with today: would you rather be impoverished and worried about food in Victorian London, or impoverished and worried about Grooming Gangs in modern London? The problem is at least as widespread now as it was then, and the spiritual conditions are worse as the material ones are better. This book shows the reality of life in the era’s dominant city, good and bad, and is a fabulous read, if depressing at times.

Tremors Under Olympus, Then the Fall

As Emmerson puts it in 1913, “A European could survey the world in 1913 as the Greek gods might have surveyed it from the snowy heights of Mount Olympus: themselves above, the teeming earth below.” While perhaps true of all Europeans, that was most true of an Englishman. His country was not quite as superior as it had once been, to be sure—German and American industry were eating away mightily at his lead as New York’s merchant bankers threatened London’s preeminent position—but was still undoubtedly superior.

There were no competitors to the Royal Navy, only enemies to defeat. All other empires, even the French, paled in comparison to that of the British, and now that the fixed costs in railroads had ports had been paid off, those colonies looked like they’d become increasingly profitable for the Metropol. The British Army had been humbled in South Africa, to be sure, but was not South Africa and its Midas-like gold fields not now theirs?

In almost every respect, then, Britain was the preeminent country. And even in those areas of life in which it had fallen behind, namely industry, it still held a commanding position that all but a few nations envied.

But there were tremors under Mount Olympus, the worst of which was the Parliament Bill. passed in 1911 had stripped the Lords of their right to veto legislation permanently, or financial legislation at all. As a result, all men of position and property now stared down the barrel of a legislative gun wielded by spiteful men like Lloyd George. The “People’s Budget” taxes rammed through by Winston Churchill, the budget that sparked the fight over the Parliament Bill, indicated what the Liberals would do with that gun. While the middle class remained firmly on the side of the established classes, the working class, harmed as it had been by years of free trade that put British industry and agriculture on its back foot against ruinous (wage-cutting) competition, were drifting toward socialism as represented by Labour. It was a problem that could hopefully be managed with tact and prudence, but a problem nonetheless.

Further, it was a tremor that showed the dire direction in which the country was headed. Britain before the Parliament Bill had been governed and administered largely by gentlemen, both of old and self-made families.3 By and large, the exceptional were in charge, and society lavished rewards upon those of ability and agency. No longer. Now it taxed the competent and successful at increasingly extortionate rates to pay for the welfare safety net for the less competent, stripped the traditional elites of much of their political power, and was generally organized around being hostile to them. Politics was now class warfare, and the resentful side of “equity” was winning.

Then came the cataclysm. Ferdinand was shot, the Germans marched into Belgium, and Britain was at war. Only, this was a continental war like no other for Albion. Whereas in the past she had financially subsidized her allies while her armies threatened descent, provided by the navy’s mobility, and that sword only dropped when it could be done with relatively few casualties and a smaller army, now a million-man army poured into Flanders. Over the course of four years, it suffered a million casualties while the Navy was humiliated at Jutland.

The British came out of the war in a surprisingly strong material position—their industrial sector was in a better place than it had begun the war, their merchant marine and Navy were still intact, and their empire had grown as they absorbed the German colonies and Ottoman outlying territories—but a very weak moral one. Whereas the British could have entered the new world created by the Great War still atop Olympus, having defeated the potential continental hegemon and ready to continue the imperial experiment without fears of another general war, they were depressed and spiritually broken. The empire seemed tarnished by the bloodletting, the onerous wartime taxes had made life difficult and chased capital out of the country, and so the victory was mere ashes in their mouths.

The postwar years then saw disorder and disaster instead of capitalization on victory. The transition back to a gold-backed currency brought not a return to Victorian power and splendor, but deflation and financial pain. The Labour government of Ramsey MacDonald didn’t appease the working classes, and instead led to (much to even MacDonald’s chagrin) a near-disastrous General Strike that ravaged the economy. Fights over gold, capital, war reparations, war bond payments, and similar financial matters bedeviled the former Allies, particularly the Anglo-American relationship. Then the Great Depression caused yet more financial disorder and pain.

All the while, the consequences of the Parliament Bill continued snowballing, and peacetime taxes remained onerous while the government was led not by the gentlemen it once had been commanded by, but instead by varying degrees of ineffective and uninspired creatures of democracy. Chamberlain, despite the degree to which he’s reviled today, was probably the least terrible of the interwar bunch. While some men involved were scions or old statesmen, as they had been for centuries, most were not. That block of the country, long the most powerful and committed to leadership, had been largely pushed out of the halls of power, and replaced with bureaucratic-type non-entities.

This domestic human capital problem was exacerbated not just by the plunging state of national morale by wartime casualties—most of the early war volunteers (Britain’s bravest and best) had perished, as had nearly a quarter of Old Etonians (the traditional elite)—and flight to the imperial dominions, where taxes and regulation were lessened.

So, with most of its best men dead or gone to Canada and Rhodesia and its status as the financial capital of the world decaying into mere dust, Britain muddled its way into a new world war. That one brought an end to the whole experiment, particularly because the consequences of the Parliament Bill exacerbated the consequences of war to a dire degree.

A Reading List for This Period

The Diehards: Aristocratic Society and Politics in Edwardian England by Phillips: This book describes the efforts made by members of the old peerage to oppose the Parliament Bill, with a full discussion of why they were fearful of the democratic tendencies expressed in it and how they attempted to stop it, along with a full discussion of how the cowardly king was the lynchpin that made it all happen. It’s a succinct, extremely enlightening read.

The Decline and Fall of the British Aristocracy by Cannadine: Though a depressing read, this is a well-written and intellectually honest book on why the British elite became a non-entity in the interwar period. Starting in the 1870s and largely concluding in the 1930s, Cannadine shows how the British landed elite went from being the men atop Olympus they were in 1900 to a class nearly devoid of its prosperity, prestige, and political significance by 1939, with worse developments yet to follow. Cannadine shows how both government policy, enabled by democracy, and a mixture of fecklessness and rejection of old values on the part of aristocrats led to this.

The First World War and Its aftermath and The Origins of The Second World War (contained in a great set) by AJP Taylor: Taylor describes in these works how Britain was not left materially devastated by the First World War, but rather crushed by a spiritual ennui that left it unable to take advantage, on a grand scale, of its material advantages any longer. The ash and rot feeling I described is largely what Taylor shows as he painstakingly puts even the casualties of the war in context of emigration to the empire in the years leading up to it, showing that though the war was a tragedy, its main results were spiritual rather than material, at least in Britain. That is an important point, and he shows it well.

The Long Weekend: Life in the English Country House, 1918-1939 by Tinniswood: The interwar period was in many ways a reprieve, as the taxation on and bureaucratic meddling with, the great estates dropped from “punitive” to “onerous.” However, it was also a warning that life could not and would not continue as it had been

Bendor: The Golden Duke of Westminster by Leslie Fields: If there is one man who epitomized the ruling class over the “tremors” period, it’s Bend’or. He came of age during the Boer War, in which he served in a leadership position with a great deal of bravery. He then led the Diehards in the House of Lords against the Parliament Bill, using his vast resources (ownership of much of London) to fight the Liberals in their attempts to push democracy on the country. He went on to invent the armored car and fund, out of pocket, its creation in the early days of the Great War, and used it to rescue over a hundred POWs from certain death at the hands of the Ottomans. In the interwar period, he showed both how the financial and human consequences of the fight in Flanders had made the Old World lifestyle near-impossible, even for a man of his wealth, and how government policy chased capital like his out of the country and into the dominions (he invested heavily in Australia, Rhodesia, South Africa, and Canada). He then went on to warn against another general war in Europe, correctly predicting the consequences, and was slandered as being a “Nazi” despite his war hero status. Finally, his life in the early postwar period showed how English life had decayed so dramatically, and the trusts created by his will showed the degree of financial engineering necessary to survive in a hostile, democratic world.

The Transition from Aristocracy 1832-1867 by Christie: Though about an earlier period, the Reform Bill time, this book is relevant here because it shows what led to the more democratic trends in British political thought and how the earlier elite, more confident and capable as it was, was able to let off its steam without giving up completely. Further, the choices made during this period can be thought of as what eventually led to the Parliament Bill.

The British Way of War: Julian Corbett and the Battle for a National Strategy by Lambert: If you are interested in why the Great War went the way it did for Britain, this is a must-read, as it puts the war in the context of centuries of British military strategy, showing how getting bogged down in the trenches of Flanders was an unnecessary and disastrous deviation from prior policies.

Olympus Falls

While World War I was a human catastrophe, though not the empire-ending event many perceive it as, the Second World War was both. Half a million of Britain’s best, now more needed than ever, died for unclear political objectives (was Poland saved from tyranny?) Meanwhile, the remaining wealth of the nation, even down to golden wedding rings, was liquidated as Churchill’s government bought American weapons that we were soon giving the Soviets for free, and Japanese forces overran the Oriental colonies and thus shook the illusion of British superiority that had built the empire. The ignominious fall of Singapore was particularly disastrous in that regard.

But while the human catastrophe was tragic and imperial disaster a mess needing to be fixed (they weren’t), the worst long-term consequences of the Second World War were financial. The tax rates on large incomes (often made large by out-of-control inflation), rose to nearly 100%, and made it impossible for the established powers to live lives of the sort that once defined British country life, thus causing cascading consequences for those dependent on them. Whereas the old system had drawn wealth and investment into the countryside, supporting farms and building modernized housing, that died. The old families lost most everything—with the government even wrecking the houses it took over during the war and refusing to fix them after—and so had to work instead of managing the great estates, drawing yet more wealth into London and out of everywhere else.

The cascading consequences of that were extremely severe. Farming, no longer supported by landlord investment that had provided the money necessary for expensive endeavors like field drainage, fell to pieces and was no longer profitable on its own, reducing the food supply and leading to expensive government subsidies. Manufacturing was largely non-competitive, as it had been ravaged by wartime demands, and so the empire was more a burden than a blessing. The world’s financial capital became New York rather than London as capital fled Britannia to avoid its extortionate taxes and domestic non-competitiveness.

Then the socialist Attlee government nationalized most of what remained, from the iron and steel mills to the coal mines and railroads, along with the Bank of England and hospitals. This thus financially decimated the already harmed elite yet further, and put more power in the hands of bureaucrats. So too did the rationing that remained in effect into the ‘50s, and the never-ending fines and taxes that came with Labour rule and feckless, imprudent Conservatives like Churchill.

Those who had once administered, governed, and invested in the Empire were then wiped out financially and chased out of service. The empire lost the very men who could have potentially guided it mostly intact toward a brighter future, and who would have led the armies that put down native revolts within it. They were preoccupied with and embittered by their battle for domestic survival, and so left the empire to others.

With the bureaucrats in charge of it, the empire was promptly handed over to the communist rebels, who stole what British property remained within their borders (including vast tea and rubber plantations into which British nationals had poured their lives and fortunes). Britain then retreated to the home islands, losing in the process the export markets that had made it wealthy and the chances for great opportunities that allowed its talented men of small resources to rise to prominence. All that reeked of the Old World, and so was wiped away.

By the 1960s and ‘70s, the Olympian Old World was firmly wiped away. A few old families still struggled to hang on, namely the Grosvenors and Percys, but most had seen nearly all they owned liquidated to pay the taxes placed on them by the bureaucratic, socialistic regime. With the Parliament Bill, they had lost most of their political power. Now, with the consequences of that democratic revolution firmly in place, they were being destroyed by those democratic forces it unleashed.

The resultant effects on leadership in Britain were predictably severe. With all the old leadership families either wiped out, chased to the colonies (particularly Rhodesia) to hide from the taxman, or embittered by decades of what they saw as unfair assault upon them, political leadership completely devolved from the gentlemen to the bureaucrats and managers. No longer were the old families who had centuries of tradition to a particular place and its people, for whom they largely cared deeply, in charge. No, now those who ruled were a mix of spiteful and inept bureaucrats who were uncomfortable around those who represented old Britain,4 and so worked to remake it in their rotten image. This is what led to the Grooming Gangs, and like despicable tragedies.

A Reading List for this Period

Noble Ambitions: The Fall and Rise of the English Country House After World War II by Tinniswood: The great change over this fallen period was the relative non-involvement of the formerly landed elite in political matters, both because they were screened out and chose not to participate. This book shows why, discussing in detail how the endless taxes and regulations imposed by the bureaucrats chased many into a myopic focus on their own (vastly diminished) fortunes. That left them embittered and both spiritually and financially neutered, speeding the transition to bureaucratic rule.

From Third World to First: The Singapore Story: 1965-2000 by Lee Kuan Yew: This book indirectly shows how the empire fell to pieces even when and where it need not have, and how the sort of incompetence in Britain’s halls of power made that all the worse. From needlessly eschewing investment in a burgeoning economy to not just handing off but pushing away what imperial possessions it could have kept and profited from, the postwar period saw Britain reject the very policies that had once made it Olympian.

The House of Morgan: An American Banking Dynasty and the Rise of Modern Finance by Ron Chernow: As this book covers all of these periods, I struggled with where to put it. However, here is probably the most appropriate, as it fits quite well with Lee Kuan Yew’s book. In it, Chernow shows how terrible British policies over the 20th century culminated in it losing its financial preeminence to America, and the immense consequences of that for Britain. Importantly, much of that came not because of world events outside British control, but explicitly because of bad policies pushed by the democratic, often socialist, regime. As financial might was much of the backbone of British success from the early 18th century on, losing its leadership position was a catastrophe for the British state, and Chernow shows that whole situation quite well.

The National System of Political Economy by List: While much of what is described in this book as applied to Britain occurred during the mid-19th century, the consequences were delayed, and only became dire in the post-war period, for that is when Britain’s economic issues made themselves most felt. This book is a must-read for understanding the importance of tariffs to a healthy industrial sector, and where Britain went wrong.

The Landowners by Sutherland: Because of the cultural cachet attached to it, its status as one of the few stable assets that increases in value and revenue with inflation, and its attachment to the ruling elite, tracking land ownership in Britain is a useful way of showing who is in charge and what happened that led there. What Sutherland shows in this book is that the middle half of the 20th century saw vast liquidations of old estates, with the land ending up

How the Crumbling of Olympus Led to the Present Horrors

By the 1970s, then, Britain was firmly in the hands of the bureaucrats and their ilk. It had been mismanaged into poverty, tax rates were extortionately high, the pound sterling was becoming an inflation-ravaged joke of a currency, and all that had remained of the African empire—Rhodesia—was in a state of open revolt. The old classes had been ushered off the scene and replaced with absolutely terrible incompetents.

The conventional narrative is that Margaret Thatcher came along and saved everything with a mix of sternness and re-privatization of nationalized industry. In some ways, that’s true. She at least restored some of Britain’s spirit, and the 80s were a better time than the preceding decades for most classes. However, there were major issues that remained. For one, she attempted to reform British industry by distributing it across the country instead of keeping it in large centers; this ended up destroying it because what few economies of scale had remained disappeared. Further, her rule took the financial boot slightly off the neck of old leadership classes, but didn’t bring them back into power. Embittered by decades of unjust and extortionate policy, they largely remained focused on personal matters rather than duty and leadership. Bureaucrats and technocrats ruled in their stead.

The 90s saw those trends accelerate. There was some degree of financial prosperity, particularly in a very degraded form of investment banking, but it came alongside continued bureaucratic rule and its discontents. This is when immigration into Britain began accelerating, and suddenly left the country flooded with foreigners.5

Meanwhile, the morals of the British population degraded severely. All the old practices and restraints upon anti-social behavior imposed by Christian civilization, the sort of things the old elite had done their best to epitomize (outwardly, at least) fell away. Replacing them were the cardinal sins that define modernity: lust leading to a massive jump in the rate of bastardy and single motherhood, greed and envy leading to excesses in the financial sector, sloth as the population fell back on the safety hammock, and so on.

What had been the pleasant society of the Shire became, in many places, like America at its worst: entire blighted regions wracked by broken homes, drug addiction, reliance on unwholesome (highly processed) food, welfare dependency, and the like. The elite was no longer doing its duty and setting a good example, focused as it was on pecuniary pursuits or publicly satisfying its base desires. With no good standard set for it by the privileged and welfare open to all who wanted it, much of the population devolved into a chasing of the deadly sins, and was enabled in doing so by the bureaucracy.

That pairing of a broken people with spiteful bureaucracy and mass immigration is the situation that led to the Grooming Gangs and like horrors. More and more former colonials poured into Britain’s urban zones, ostensibly to work. They too ended up relying on the welfare hammock, using it and their ethnic solidarity to start taking advantage of British girls while sucking the lifeblood from British taxpayers. Nearly all of their victims were from impoverished families and broken homes, with no one to look out for them as the foreigners preyed on them.6

The local bureaucrats either didn’t care about the fate of the left-behind girls or were actively in on it, themselves joining in the abuse.7 The national bureaucracy and its “leadership” weren’t just uncaring, but actively wanted to suppress news of the horrors and avoid justice for the victims because of their commitment to anti-racism.8 Equity was more important than justice, particularly for the despised native-born. And the social elite had abdicated its responsibility, shying away from duty out of bitterness and a need to focus on its finances. So the lords were no help either.

Such is how you get stories like the one that has taken X by storm, where a young girl had to carry around a knife and a hatchet to protect herself from a gypsy immigrant who was trying to rape her and her sister…and he was let off by the police while she was arrested for brandishing a weapon.9 This is despite the fact that he had left the girl’s sister hospitalized when he sexually assaulted her. Britain is now a land so evil it would be comic if not so sad. (You Can Donate to Help Her Family Here)

That is all the result of the trend toward bureaucracy described. In the days of Olympus, there is no chance that gypsies and Muslim economic migrants would have been allowed to prey on young British girls. They would have been executed, and if the state refused its duty, the lords and their people would have made it happen in private fashion. There were men who were clearly in charge, and it was their duty to protect Britain from such horrors.

That sense of duty and responsibility died as the bureaucracy rose. The Parliament Bill and its consequences were disastrous, not only in that the taxation and imbecilic policies enabled by them impoverished the country and lost the empire, but in that the bureaucracy it enabled has no sense of duty or responsibility. It is a grey blob that is far to the left,10 and thus hates the British people, and cares far more about staying in power than doing anything positive for the people of Britain. It’d rather replace them with despicable foreigners, much as the American regime has done.11

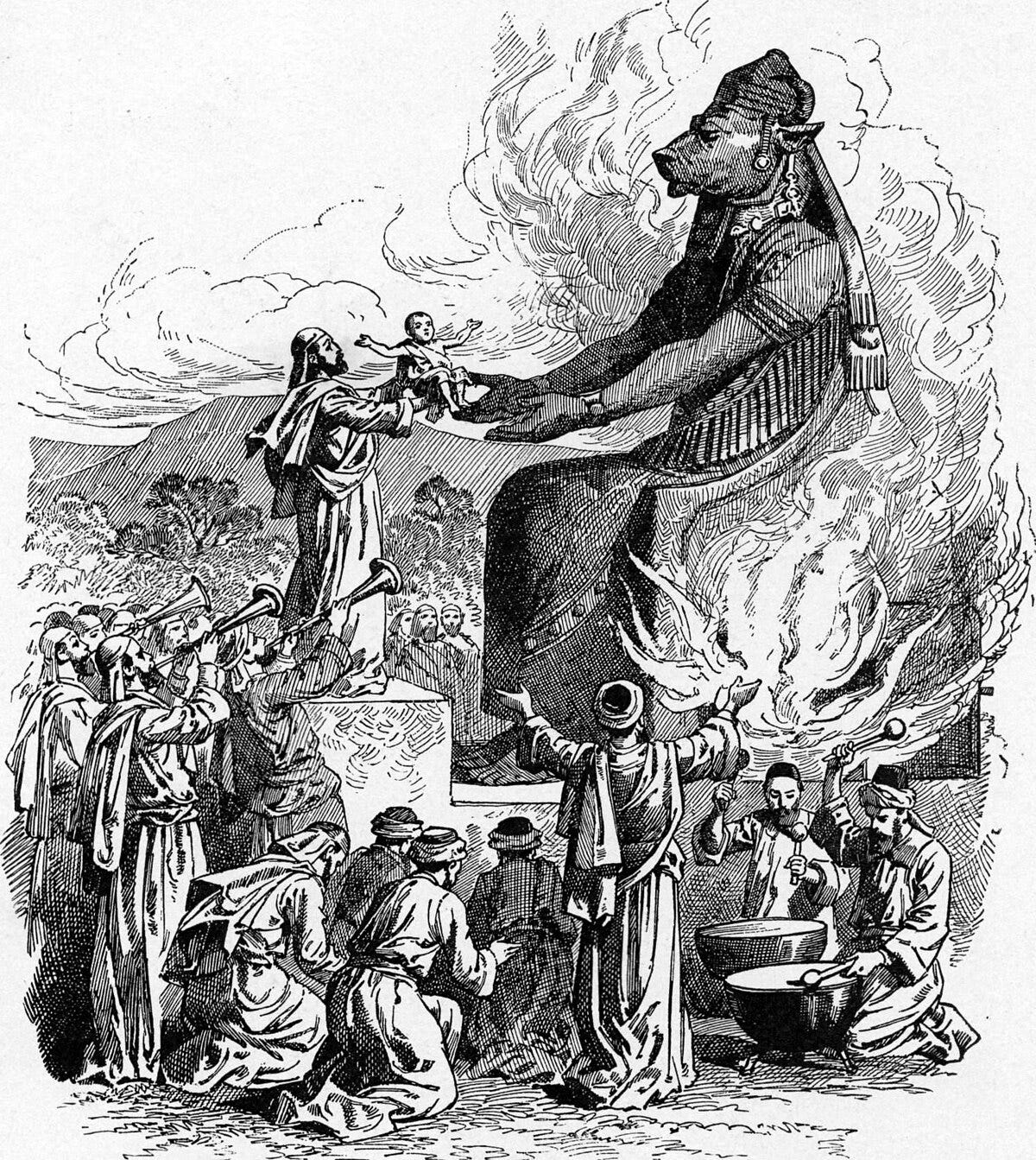

There is much blame and responsibility to go around. The old elite should not have been chased from power and crushed by unjust taxation, but it should be doing its duty now, as it very much is not. Britain is in a dark place. The only way it will again clamber atop Olympus is by returning to the old ways, restoring the society it built over centuries of hard work, social accommodation, and investment. All of that accumulated capital, both social and financial, has been liquidated atop the arms of a liberal Moloch. But it can be restored, and it is the duty of the privileged few who are left to start leading it there. That duty can no longer be ignored, for if it is, their island story will finally come to an end, with the British people choking on their own blood.12

A Reading List for This Period

Our Culture, What's Left of It: The Mandarins and the Masses by Dr. Theodore Dalrymple: In this book, Dr. Dalrymple shows through his personal experiences as a doctor how the British working class has largely degraded into a welfare-reliant, drug-addicted underclass with all the neuroses that could be expected of such a group. Fatherlessness in the home, frequent wifebeating and interpersonal violence, substance abuse around children, and endemic joblessness are all the traits that sadly characterize this group. I think that helps put the Grooming Gangs scandal in context, and shows how both the lack of leaders and lack of virtue made the sickening situation possible

Tragedy & Hope: A History of the World in Our Time by Carroll Quigley: This is quite a long read, but well worth it, as Quigley exposes how all of what I described led to the present state of terrible rule in Britain. Particularly, he shows how the overthrow of the old elite led to 1) bureaucratic rule that is far harsher and more extractive than what the Old World elite did, and 2) how the cultural overthrow of that old elite became a virtue-destroying phenomenon, with the worst traits of the bourgeoisie becoming the most emphasized “values” in society. Further, Quigley shows the present composition of the Anglo-American power structure and its roots in finance rather than land, helping explain the lack of any sense of duty that characterizes it.

I am yet to read any good books on the Grooming Gangs (recommend one, if you know of it), but most of what’s important on the sickening details front can be gleaned from the headlines. What really matters, I think, is how any of that was allowed to happen in the first place: the death of duty and virtue at the hands of a bureaucracy

Thanks again for reading! If you found value in this article, please consider liking it using the button below, and upgrading to become a paid subscriber. That subscriber revenue supports the project and aids my attempts to share these important stories, and what they mean for you. Also, it gets you full access to paywalled articles, like the recent article on lessons for Americans from the Rhodesian Bush War.

For example:

And:

For a full study of this concept, read:

This was even true outside the country. JRT Wood notes that Harold Wilson, when negotiating with the Rhodesians, was left feeling jealous and insecure around the Duke of Montrose, who was serving in the Ian Smith government. Described here:

The background of the girls covered here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rotherham_child_sexual_exploitation_scandal

Noted here: https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cn9y0lvpyqvo

They’re even to the left of their voters: https://academic.oup.com/book/26026/chapter/193919768

“If this long island story of ours is to end at last, let it end only when each one of us lies choking in his own blood upon the ground.”

―Winston Churchill

Ironically, that wasn’t going to happen then. But thanks to Churchill and his People’s Budget, along with all that followed, it is on the verge of happening now

Well done! I would add that Free Trade started this whole mess by destroying the profitability of British agriculture, thereby wrecking Britain's previously stable rural society, where country prelates had sufficient time and income to make important scientific discoveries, and greatly weakening both Lords and the middle class that depended on them...

Another fantastic article